Uncovering the hidden history of local ayahs

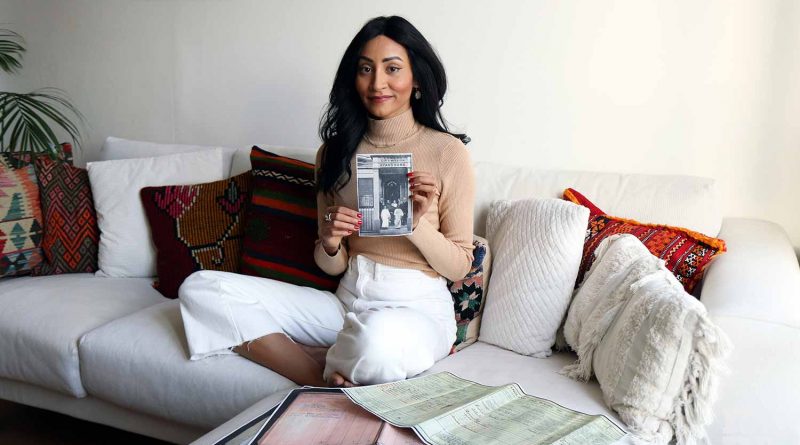

Farhanah Mamoojee from Bow Quarter is campaigning to get a blue plaque to mark the historic presence of local ayahs – nannies brought to the UK from colonial India in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

With a background in History of Art, and now working at Sotheby’s, Mamoojee, 28, has always been interested in uncovering the historical stories of people from marginalised backgrounds: those who are less present in today’s collective memory due to their lack of power, wealth, or social influence.

When she moved to Bow in 2014, Mamoojee was struck by the local area’s long history of fighting for women’s rights. Even her own housing development, Bow Quarter, used to be the Bryant and May match factory: the site of protests in 1888 by female employees against harsh working conditions, which are now known as the ‘match girl riots’. Nowadays, the revolt is recognised as an early instigator of union rights.

‘There is so much activist history here – not just the suffragettes and the campaigns for women’s rights, but working-class women’s rights as well.’ says Mamoojee.

When Mamoojee stumbled across the plight of ayahs in her area while watching a documentary about Britain’s migrants, she was inspired to take action and do her part in bringing lesser known local history to light.

Ayahs were essentially nannies from colonial India and other parts of Asia who were charged with looking after the children of wealthy families during their sea voyages to and from colonial Britain.

However, no formal contracts or promise of voyages back to their home countries were made, which meant that once here, their services were no longer necessary. So the ayahs would simply be dismissed: effectively abandoned in a country foreign to them, with no employment or place to stay.

The issue of abandoned ayahs in London became so prolific that the missionary charity, London City Mission, opened a shelter for them to stay while more work or journeys home were negotiated in the meantime.

The mission is on 4 King Edward’s Road, just north-east of Victoria Park. When Mamoojee discovered it was only a few minutes walk from her flat in Bow Quarter, she investigated the former home.

‘When I got there, I thought there would be something there to commemorate the fact that ayahs lived in that building; like a small notice board or anything signifying its history,’ she said.

‘But there wasn’t anything: it looked identical to all the other houses on the road. And I was really disappointed because the histories of women, and of migrant women, add so much to our collective identity and people’s sense of belonging. So there should have been a marker.’

Determined to make sure the presence of the Ayahs’ Home was acknowledged, she got in touch with her local MP about setting up a blue plaque.

She made an application for a plaque, which has now been shortlisted by English Heritage, who run the blue plaque scheme.

In the meantime, Mamoojee continues her investigations into the ayahs, trying to trace their descendants: a near-impossible task given that many of their names have been lost to history.

‘A lot of their names were erased or just not recorded at all in the first place because they were simply not seen as important enough’, she says during the interview, pulling out a piece of paper with a scanned image of a yellowed, old record sheet. It is a census from 1911 showing the records of those living at the Ayahs’ Home.

‘Here,’ she says pointing to a scribbled line, ‘you can see there’s an ayah called Mary Fernandez. It is very unlikely that was her real name because she would have been South Asian. And her records stop there. I couldn’t find any more details of her family or what ultimately became of her.’

Mamoojee also found naval records showing the families who travelled to and from the UK.

‘Most of the time, the families’ names will be recorded, but not the ayahs. It will just say, “the ayah that belongs to this particular family.”’

While she is waiting to hear back from English Heritage about the final decision on the blue plaque, she is holding an event at Hackney Museum exploring the role of the ayahs during the British Empire, including poetry workshops and lectures from the rare few historians who have researched this group of women.

Why does Mamoojee feel passionately enough about the ayahs to apply for blue plaques and organise a whole day’s events on top of her full-time job at Sotheby’s?

‘I want everyone who lives here to be connected to our history because it creates a sense of belonging for everyone.

‘Even though I feel at home in this part of London and I feel very connected to its past – I’ve noticed that many in the local community are not very engaged with local history, maybe because more marginalised peoples are relatively less well documented.’

With this event, which is free for all to attend, she hopes that everyone in the local area can get a better sense of who they are by developing a better understanding of our collective past – of the working and migrant women that history has ignored, but perhaps not for much longer.

Follow Farhanah on her journey as she uncovers the stories of the ayahs on her Instagram account.