Bow: the heartland of Sylvia Pankhurst’s life and work in East London

Few people realise that Bow is the heartland of Sylvia Pankhurst and the East London Federation of Suffragettes. Within 100 metres of Roman Road – east, south, north and west – lie the sites of the Suffragette’s East End head quarters, their revolutionary enterprises and the bloody battles that mark key moments in the history of women’s suffrage.

The votes for women campaign began in the second half of the 18th Century, but many of the names and endeavours of the original pioneers have been forgotten. For most people, the most recognisable members of the campaign are the Pankhursts – mother Emmeline, and daughters Christabel and Sylvia.

But it wasn’t the great united front that the vision of three women, three members of the same family, fighting for the rights of women, might conjure up. There were distinct schisms between the Pankhursts that would eventually see Sylvia breaking out on her own in Bow.

Emmeline Pankhurst had five children, and was a widowed, single mother by the age of 40. Her two sons – one of whom died in infancy – don’t feature in this story; nor does her daughter Adela, who moved to Australia.

Emmeline, Christabel and Sylvia, founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in Manchester in 1903. The banners and murals, hats, and badges, in the green, purple and white colour scheme of the WSPU, were designed by Sylvia, who was a talented artist. She went to Manchester School of Art, and then got a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in London – no mean feat at the time! When Sylvia moved to the capital to study, she was already aware of the work being done in East London, not only in support of the votes for women campaign, but to improve the situation of working women of the area. Sylvia’s desire that the WSPU embrace this, too, was not looked upon favourably.

The WSPU was not a votes for all women initiative, it was only really interested in helping middle class, upper-middle class, and property-owning women. Sylvia, on the other hand, felt it was just as important – if not more so – to champion the rights and conditions of those at the lower levels of society. It was this difference of opinion between Sylvia and the WSPU which would ultimately see her expelled from the group.

Broadly speaking, there were two groups involved in the campaign: the moderate suffragists, who wanted to campaign by discussion and negotiation, and the suffragettes, the radical ones who preferred direct action.

The word ‘suffragette’ was coined by The Daily Mail in about 1908 or 1909. It was intended as a negative term for the votes for women campaigners – by adding ‘–ette’ to the end of a word, they intended to belittle it. But the women liked it, and adopted it as their own.

Women’s Social and Political Union at 198 Bow Road (1912-1913)

When Sylvia came to London, she opened an East London branch of the WSPU, which would ultimately become known as the Bow Branch.

In October 1912 she climbed on a little set of wooden steps and painted on the frontage: ‘Votes For Women’.

Bow Baths battle, 555-559 Roman Road (1913)

Where the Gold-n-Image jewellery store and Sinclairs Pharmacy now stand, is the former site of the Roman Road baths, built in 1891. At a time when people lived in cramped and crowded conditions, without indoor facilities, bathhouses proliferated all around the country. People went to bathhouses to do their washing, to swim, and to bathe in private cubicles – a luxury not available to most in their own homes.

In these bathhouses it was often possible to cover the swimming pools with slats of wood, turning them into meeting rooms, which is what they did here on Roman Road, and it is where Sylvia held many of her WSPU meetings.

By 1913 the WSPU had been operating for 10 years, and the police were well aware of their activities, which increasingly involved property destruction, arson and bombings. Very few of the acts carried out by members of the WSPU are known individually, except for Emily Davison throwing herself at the King’s horse in June 1913, and Mary Richardson slashing the ‘Rokeby Venus’ at the National Gallery in March 1914. But there was a sustained campaign of activity, from smashing department store windows and setting post boxes on fire, to bombing and committing arson at golf and cricket clubs.

So when Sylvia began holding her meetings here, the police were ready, eager to break up proceedings, and mete out some ‘justice’ (read: violence) to the suffragettes.

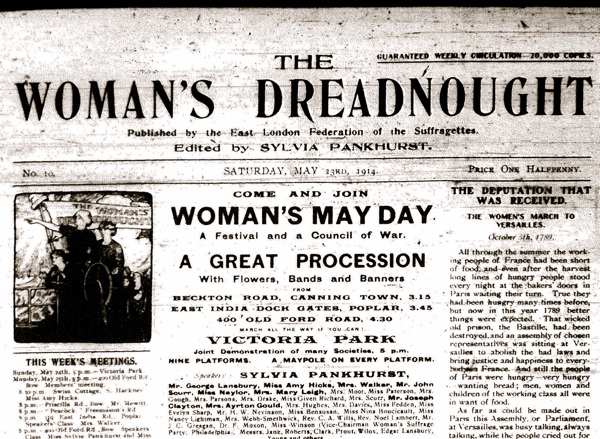

By the end of the year Sylvia recognised that her supporters needed to learn how to defend themselves against what she called ‘the brutality of public servants’ and launched a people’s army at the baths. Around this time it was not uncommon to see her disciples marching up and down The Roman, but also selling the votes for women newspaper, which subsequently became the ‘Woman’s Dreadnought’ (on which more later), to raise funds for the cause.

New headquarters at 321 Roman Road, Bow (1913-14)

After a short time on Bow Road, Sylvia acquired a new property for her WSPU headquarters on Roman Road. She wrote of the February day she took on the premises: ‘The sun was like a red ball in the misty, whitey-grey sky. Market stalls, covered with cheerful pink and yellow rhubarb, cabbages, oranges and all sorts of other interesting things, lined both sides of the narrow Roman Road. The Roman, as they call it, was crowded with busy, kindly people. I had always liked Bow. That morning my heart warmed to it forever.

‘We decided to take a shop and house at 321 Roman Road, at a weekly rental of 14s 6d a week. It was the only shop to let in the road. The shop window was broken right across, and was only held together by putty. The landlord would not put in new glass, nor would he repair the many holes in the shop and passage flooring.

‘It had lately been a second-hand clothes dealer’s and was bug-ridden, like many another East End hovel. Repeated fumigation and papering never entirely eradicated the pests. In spite of such drawbacks, the place was a centre of joyous enthusiasm.

‘Plenty of friends at once rallied round us. Women who had joined the Union in the last few weeks came in and scrubbed floors and cleaned windows. Mrs Wise, at the sweet shop next door, brought in a trestle table for a counter, and helped us to hoist the purple, white and green. Her boy volunteered to put up and take down the shutters night and morning; her girl came in to sweep. Friends rallied round; women of the neighbourhood scrubbed the floors and cleaned the windows; tables and chairs and crockery were given by poor people’s self-denial.’

Marching to Victoria Park (1913-14)

In May 1913 Sylvia wanted to stage a procession to draw attention to the campaign for votes for women, so she arranged a march that went from the gates of the East India docks all the way to Victoria Park. It was a procession full of hope and aspiration, with many people wearing the red caps of liberty Sylvia had designed, carrying sprigs of green, and dressed in the green, purple, and white of the WSPU.

At Victoria Park they had erected platforms for speakers such as (at that time former) Labour MP and votes for women supporter George Lansbury, and trade union leaders, to talk in favour of the campaign. Of course the police were also there, and the gathering was swiftly broken up.

This support from working people and the Labour party was the last straw for Emmeline and Christabel. The latter, now living in Paris, summoned her sister Sylvia to France and banished her from the WSPU.

From then on, what had been the Bow Branch of the WSPU became the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS).

In May of 1914 Sylvia was back at Victoria Park, on another procession from East India Docks, but this one was more sombre, what with the approach of WWI on the horizon. Sylvia arrived surrounded by supporters chained around her. But the result was the same: the police were there to break it up.

East London Federation of Suffragettes at 400 Old Ford Road, Bow (1914)

This was the site of Sylvia’s third headquarters, the second for the East London Federation of Suffragettes. It was also where she started a cost-price, wholesome food restaurant. After the breakout of WWI in September, it also became a distress centre for local women who were struggling to pay the rent with their husbands away, or killed in action.

It was around this time that things started to get difficult for Sylvia, and her star began to fade. As a pacifist, she didn’t believe in war, and was anti-subscription – a stance at the time considered akin to treason. Her sympathy towards the Communist movement didn’t go down well, either. While English men were off fighting the enemy abroad, Sylvia encouraged her supporters to continue their fight on the home front.

The women’s suffrage societies carried on their campaigning during the war, too, but did so quietly, and through conversation rather than action. Meanwhile, Emmeline negotiated with the government for the release of her supporters from jail in exchange for their employment in the jobs left vacant by men sent to the front line. Three different groups, with three very different tactics, during a difficult time.

Famously, after WWI, in 1918, women did get the vote, but it was just for women aged over 30. It wasn’t until 1928 that British women got the vote on parity with men.

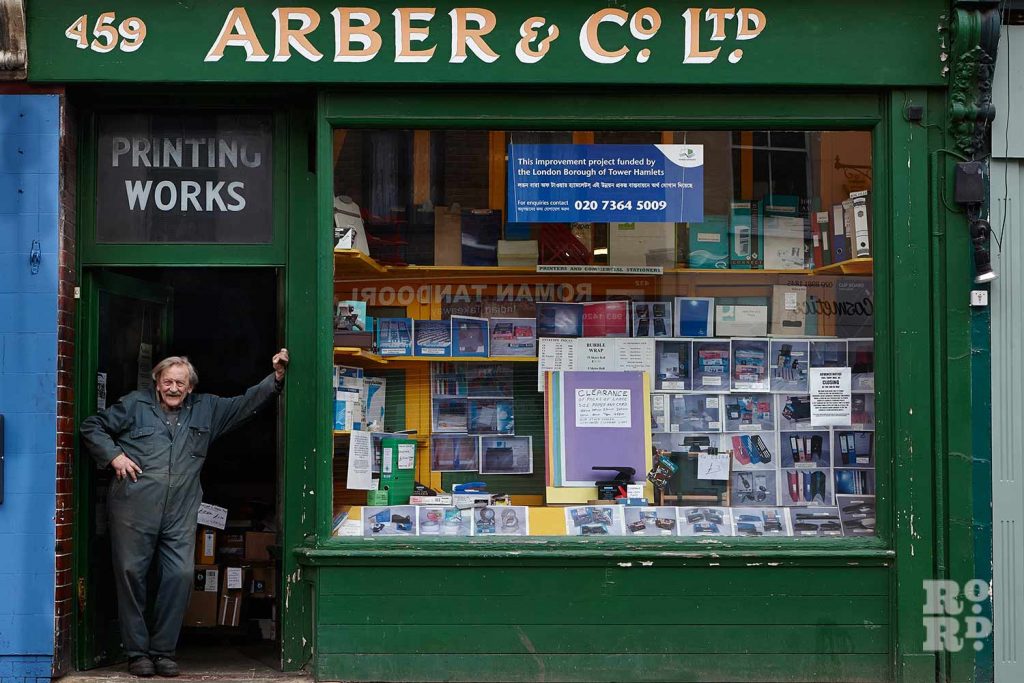

Printing Woman’s Dreadnought at Arbers, 459 Roman Road (1914-1924)

On this site, between 1897 and 2014, was Arbers, a shop run by four generations of the same family, first making boxes, then printing, along with some toy-selling for several decades. It was Arbers that printed Sylvia’s Woman’s Dreadnought, along with campaign posters and leaflets.

Sylvia wrote some pieces for the newspaper herself, but also brought in guest editors. One of those editors was an Italian called Silvio Corio. Though not listed on the birth certificate, Corio is accepted as being the father of Sylvia’s only child, Richard, born in 1927.

Toy Factory and crèche at 45 Norman Grove, Bow (1914-1934)

Now a family residence, this was the former site of a toy factory set up by Sylvia to provide work and a decent wage to local women, as well as a crèche for those who had young children. The women designed and made the wooden toys, and Sylvia went out and sold them to shops like Selfridges. The factory was on this site until 1934, when it moved to the Kings Cross area, where it continued until the early 1950s.

The Mother’s Arms, 438 Old Ford Road, Bow (1915-920)

(Corner of Old Ford and St Stephen’s roads)

On this site over 100 years ago stood a pub called the Gunmakers Arms. It was the watering hole of the workers from the factories across the other side of Old Ford Road, which made gun parts. But by 1915 the pub was sitting empty, and Sylvia was able to take over the lease, and the nursery that originally operated in the house at 45 Norman Grove, was moved to this larger premises. Her wealthy supporters gave of their money and their disused toys, and nurses and medical professionals gave of their time. The Gunmakers Arms – which the pacifist Sylvia renamed The Mother’s Arms – also became a milk depot, offered lectures to new mothers, and medical check-ups and weighing of infants.

During WWI there was a women’s exposition at Caxton Hall near Victoria and the writer Israel Zangwill, an East Ender dubbed ‘the Jewish Dickens’, was invited to cut the ribbon to open the event, and, in honour of Sylvia’s work, declared: ‘the future of the world lies in the transformation from gunmakers arms to mother’s arms’.

The nursery lasted here until 1920, by which time Sylvia’s popularity was ebbing, as were the Federation’s funds, and it closed down.

It was around this time that Sylvia decided to move out of Bow, first to Woodford, in what is now the North East of Greater London, and then, in 1956, to Ethiopia. She died there in 1960 and was buried in Addis Ababa.

Thanks to Rachel Kolsky whose Battling Belles of Bow guided tour was invaluable in researching this article.

The Eleanor Arms always gets overlooked in these reports. It is entered on the deeds of the pub that The suffragettes used it as a creche during world war 1.

Hi Frankie – if you can give us some more info about the creche, to-and-from dates, any images (maybe even a pic of the deed), we would be happy to add it to our timeline.

thanks,

Amy

Hello Amy

A brilliant gem of a website, BRAVO!

I am currently writing a historical novel based in this era and your site has provided me with invaluable information about Sylvia Pankhurst & the ELFS. I haven’t been able to find any other information about exactly when the Federation closed. Here, you say it wound down in 1920 with the close of the nursery. Did the clinics in “The Mothers’ Arms” close at the same time, do you know?

I would be immensely grateful if you could point me in any direction for further information….

Thank you