Marcus Tisson builds a mental health legacy following his mother’s suicide

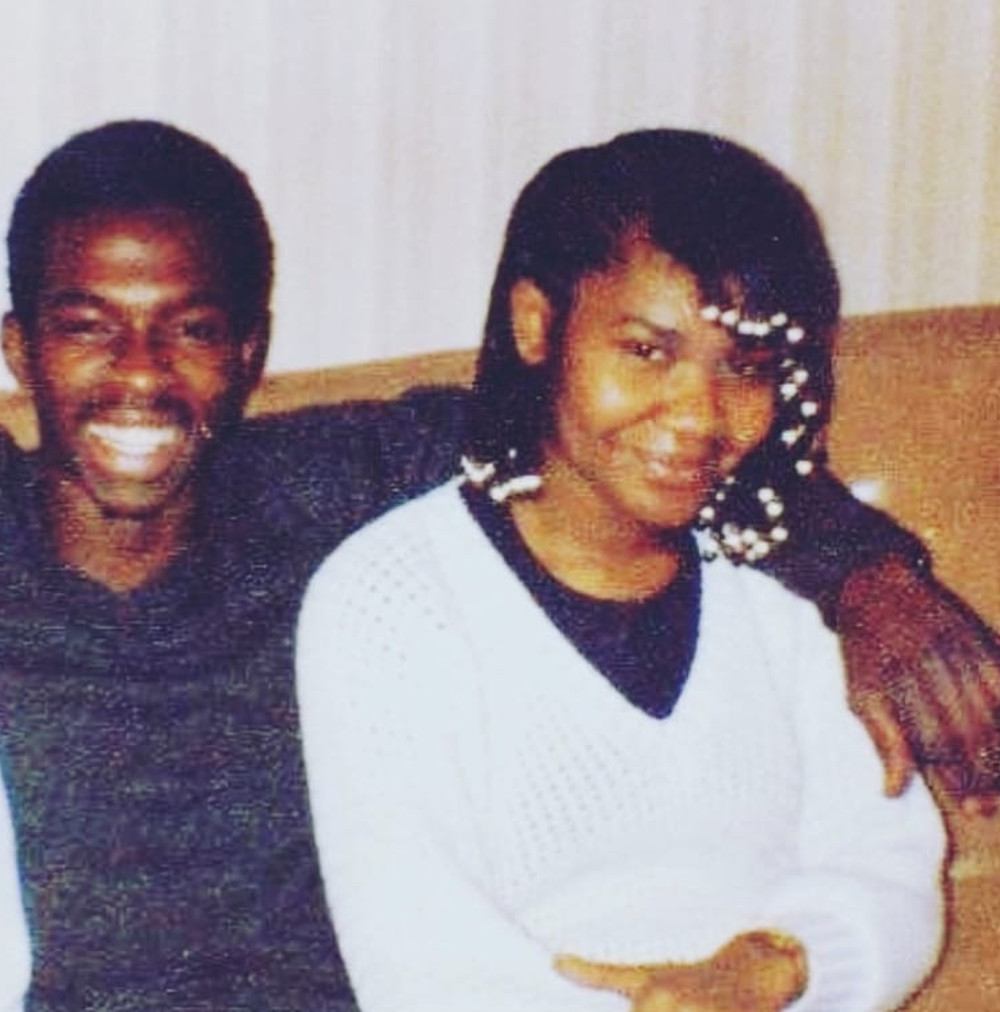

On August 21, 2016, Marcus Tisson’s mother, Margaret, jumped in front of a train at Mile End Station. Two months after that his father, Winston, who had struggled with schizophrenia all his life, passed away.

In the three years since, Tisson, 40, has devoted his life to the mental health awareness campaign Don’t Suffer in Silence. From stand up specials to black tie galas to Facebook stories, Tisson strives to release people from the constraints that keep them from talking about mental health.

Born and bred in Bow in East London. Tisson knows first hand how powerful those constraints can be. His mother didn’t speak to anyone ahead of that fateful day, and even the months that followed showed Tisson just how widespread that taboo is.

‘My circle is smaller now,’ he says. We meet at the Hub in Victoria Park, a stone’s throw away from his mother’s memorial bench. In the fallout of her death, with his mind reeling, many people distanced themselves from his grief. ‘A lot of people didn’t understand me at the beginning,’ he says. ‘I lost both my parents and the empathy weren’t there as I thought it would be.’

This is not a source of bitterness for Tisson. If anything it consolidated the idea that people are often unwilling to talk about mental health, and many would sooner bury those feelings than admit they’re there. Don’t Suffer in Silence is Tisson’s way of breaking that stigma.

The centre piece of that campaign has been comedy. ‘I believe laughter is good for the mind,’ Tissons says. ‘Even though I’m helping other people, it helps me too. It’s a way for me to rant and show my emotions.’ Over 180 gigs, and marquee events at the Backyard Comedy Club in Bethnal Green and the Lighthouse in Shoreditch, have given Tisson a platform for his own struggles. They are nights for tears as well as laughter.

Away from the stage Tisson is a learning mentor at George Green secondary school on the Isle of Dogs. He has worked in education for 14 years. He also runs mental health walks around Victoria Park. It’s a haven for him. ‘I feel happy here,’ he says. ‘Different cultures playing together, different sexualities. We’re really lucky to have Victoria Park in Bow, it’s a beautiful park, probably the best in the UK.’

The message for his students is the same as the one for his two children. ‘I always tell my kids, if anything’s wrong, to open up,’ Tisson says. ‘That’s where it starts, at a young age. Kids nowadays have such a hard time with social media, peer pressure, bullying, looking the right way. We need to teach our kids to talk, to open up.’

Tisson practices what he preaches. He’s wearing a green bomber jacket when we meet and it’s covered with patches and badges in unlikely spots. It’s an unabashed look, and it suits him down to the ground. In his videos he jokes and dances and cries and sings, because that’s what he needs to do. Trying to look conventional is just another way of silencing your real self.

Social media plays a big part in this, which is one reason Tisson uses it so much for the campaign. His raw, unfiltered approach shows a different approach. ‘There’s not enough realness on social media,’ he says. ‘I think the world would be a better place and there would be less mental health issues if people were honest with themselves.’

He cites ‘stunting for the gram’ – people renting cars they can’t afford, using filters to look differently than they really do. Every effort we make to impress other people moves us further away from ourselves.

This mindset bears out in Tisson’s stand up shows, the most recent of which was called Don’t Call Me Crazy. Throwing words like ‘crazy’ and ‘mental’ at anyone who defies our expectations of normalcy is just added pressure not to talk about it. Tisson tackles that mindset head incorporating topics like depression into his set. Like most monsters, mental health is far less frightening when you bring it out of the shadows.

Although the spark was his mother’s passing, Don’t Suffer in Silence has highlighted the difficulty men have opening up. Tisson estimates only 10% of attendees to his events are male. ‘As a black man, I think in my community a lot of men have this persona and are embarrassed to open up and show their feelings. There’s a stigma that has to stop.’

He faced it himself when his parents died. When he shared his grief some of his peers accused him of doing it for attention. The suicide rate for men in the UK is three times as high as it is for women. Tisson chalks a lot of that up to the same stigma. ‘That’s why the suicide rate with men is so much higher,’ he says. ‘They hold it in.’

Grime is a notable exception to that trend. Tisson believes the genre, which began in Bow, has provided an outlet for young people in the area and beyond. ‘It’s definitely a therapy,’ he says. ‘ It’s people talking about their lives. Grime gets stick in the media because a lot of the content is quite violent, but it’s the life they lead. Growing up in Bow, knowing Wiley and everyone who started grime, we come from an era when there was a lot of gang violence.’

Just like Tisson’s comedy, it’s a vent. ‘I don’t agree with some of the content, but it’s their life. Who are we to judge?’

Not that one’s struggles have to be out there for the world to see. Tisson puts himself out there so others feel emboldened to do the same. People can relate to the campaign because there’s a person at the front of it.

Men and women frequently contact him in private to thank him for example, or to ask for help. He points them towards the appropriate support system – be it Mind or Samaritans – and his work is done. That vital first step has been taken.

‘Not everyone is as confident as me to talk about their feelings,’ he says.’And I get that, because people do judge, they don’t understand.’

Tisson’s approach to mental health is gentle and accommodating. His only ask is that people take that leap towards communication. The form it takes, or who it’s coming from, doesn’t matter. From neighbours to celebrities like Tamer Hassan and Kerry Katona, who have gotten on board with the campaign, mental health can affect anybody.

‘It doesn’t matter what gender, what sexuality, what colour, what age you are,’ Tisson says. ‘Mental health don’t discriminate.’

Tisson has become something of a local celebrity himself due to his work on Don’t Suffer in Silence, but it’s a mantle he shoulders with buoyancy. People coming up to him in the street. Thank you for your videos, they really help me. ‘You’re the mental health guy.’ He laughs.

The deaths of Tisson’s parents was an unimaginable tragedy, but it has lit a fire in him as well. ‘My parents’ passing was a light for me to do what I was destined to do,’ he says. ‘If I can help one or two people, I’ve done my job.’ That said, there’s much more in store for Don’t Suffer in Silence. More events, more laughter, more tears, and maybe even a documentary.

Marcus Tisson is in for the long haul, and there’s no question how proud his parents would have been. ‘This is their legacy,’ he says.

If you liked this piece you may enjoy reading about East End gent Eddie Brown’s mental health story