Rachel Whiteread’s House: why was this Bow landmark demolished?

Every day people walk past Wennington Green, on the corner of Grove Road and Roman Road, without realising this was the spot on which stood Rachel Whiteread’s controversial inside-out concrete cast of an East End terraced house. Why was this Bow landmark demolished?

Wennington Green, Bow, London

At the intersection of Roman Road and Grove Road lies Wennington Green – a patch of land in Mile End Park principally sculpted by flying bombs. In fact, an English Heritage plaque on the railway bridge a little further down Grove Road commemorates the first one to strike London.

The blitz largely levelled the hundred or so turn-of-the-century terraces, common stock of the working class East End, on what is now the Green but up until the early ‘90s a row of dilapidated dwellings persisted. These residences were mostly derelict, abandoned and occasionally squatted, but for one, ex-docker Mr Sidney Gale of No. 193, a condemned house remained a home.

Indeed, in 1993, the final row was fated to be demolished as part of Tower Hamlet’s council’s plan to create a Green Corridor, unifying the broken line of parkland between the Isle of Dogs and the established lung of Victoria Park. It was a means to cleanse the area of the legacy of prefabs that had homed the dislocated population post-war and a redemptive space for those in the high-rise accommodation which had replaced the traditional terraces. ‘What people who live in tower blocks want is parkland,’ declared Councillor Eric Flounders.

Yet psychogeographer Iain Sinclair was sceptical of the council’s motives, calling it ‘an Arcadia for the underclass… the whole scheme was a disinterested attempt at municipal aesthetics’. Pointedly, the area was in direct sight of Mrs Thatcher’s commerce baby, Canary Wharf, and the call for a Green was not a far cry from the original motivations to create Victoria Park, opened in 1845. Vicky Park is the oldest purpose built recreation ground in London, conceived to curb disease contracted in damp and cramped conditions and as a means harness working-class wildness. Indeed, Bow is an area rich with connotations of a strong working-class community, but also radicalism and revolt.

Mr Gale forcefully resisted eviction from No. 193 by the council for a number of years, even festooning the property with banners to affirm his unrelenting presence, but, realising his campaign was ultimately futile, he eventually yielded and was re-homed nearby. Gale’s loss was artist Rachel Whiteread’s gain. The practitioner had been seeking a condemned property in London for over two years to realise a project which was essentially a development upon her Turner Prize nominated sculpture, Ghost (1990); a room-sized cast of a bedsit contained in a Victorian property in Archway.

Whiteread, supported by art commissioners Artangel, approached the London Borough of Tower Hamlets council about utilising the property and the authorities duly consented. In the beginning, the council were of the opinion that, ‘It won’t cost the neighbourhood a penny and will provide an unusual landmark for the area,’ however, by the time the bricks were removed and the sculpture was exposed, Councillor Flounders, Chair of Bow Parks Board, denounced it as ‘excrescent.’

Building Rachel Whiteread’s House

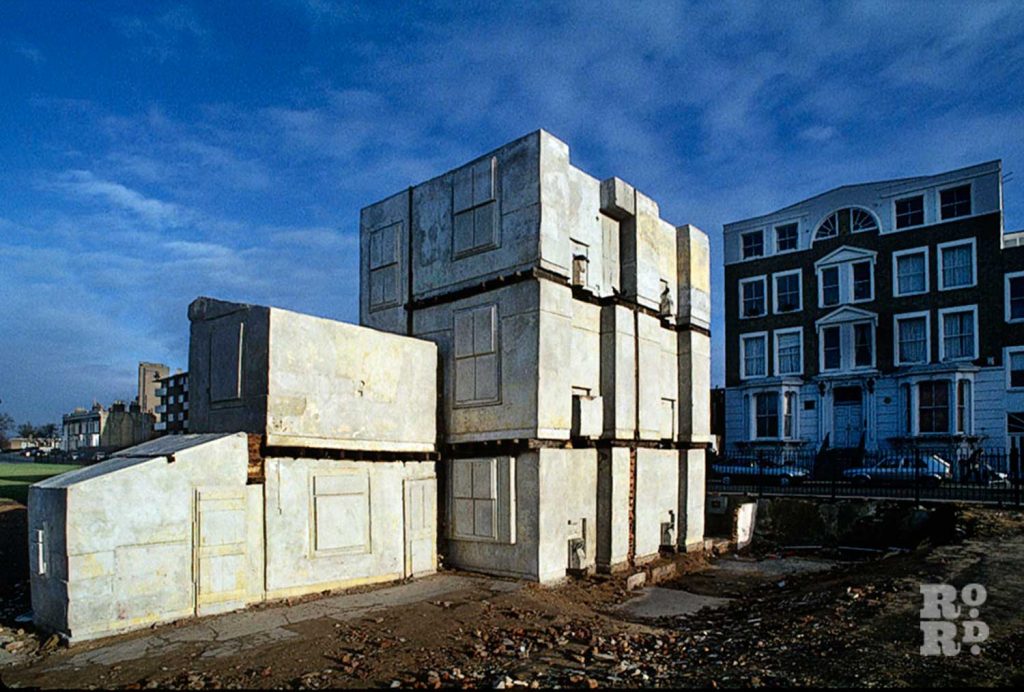

To make House, Whiteread used the physical house as a mould, making a cast from the interior by spraying a skin of liquid concrete around a metal armature constructed to support the weight of the work. Coating the whole house took over a month and an additional ten days were needed for the concrete to cure and set. Once solid, scaffolding was erected and Whiteread and her assistants began to remove the exterior brick structure.

What was revealed was an uncanny sight – the concrete impressed with the idiosyncrasies of over a century of domestic habitation. Depressions translated into protrusions; the industrial material betraying past human intimacies: soot marking the fire; yellow paint from a top-floor bedroom. The floors in-between stories could not be cast so, as local Markham Hall recalls, it resembled a ‘wedding cake.’ But the marriage at hand, between the art world and the East End, was to be short-lived and volatile.

Reactions to Rachel Whiteread’s House

It was essentially a neutral process, with no specific moral agenda, but Whiteread conceded ‘I knew of course, while I was making House, it had a political dimension. You can’t make a cast of a house in a poor area of London and not be political.’ Yet it became ‘far more political than I could have predicted.’ Seemingly, the council had also underestimated its resonance, as it quickly became front-page news, attracting scores of art-pilgrims and causing traffic chaos. Its status was even brought to debate in the House of Commons. The council couldn’t wait to get rid of the work fast enough, coming to regard it as a politically embarrassing monument to an impoverished history and standing in the way of the construction of a less threatening green space.

People reacted to House so strongly as it transcended the individual and became an archetype; an emblem for the area’s time-honoured mode of living. Indeed, it raised pressing questions regarding degrading housing stock and what should be done with it, the creeping gentrification of a historically tight working class community and scepticism towards the authority of those instigating change for the supposed ‘greater good’. In whose name was this change really for? And poignantly, it confronted these questions on its own material terms – concrete being the material used to fix the original Victorian House’s bricks; the embossed surface betraying the umbilical cords of pipes and power-lines which linked the individual house with the local, national and global public.

At base, Whiteread made an empty space, the negative void of the vacated property, into a positive object but insists ‘the work is to do with absence not presence.’ Implicitly, House was defined by the object it was not. When one refers to a ‘house’ we generally mean the façade as publicly viewed from the street, the interior is intimate – that is the home. Whiteread’s sculpture was resolutely an interior; an unsettling mass of inside, out.

The form elicited unease as when we have an intimate relationship with a space, we start to ignore its intricacies, instead handling navigating through the general form unconsciously. Thus, the sculpture was uncanny as it solidified the overlooked, demanding a long-looking, deep contemplation, as one attempted to decipher the inverted forms. Whiteread neglected to furnish her House with meaning but it was predominantly envisioned as what the populace of Bow would soon lose sight of. The interior, a family home, was left out in the cold and significantly, Whiteread chose not to cast the attic space, as if riffing on the idiom ‘left with no roof over their heads.’

It’s understandable then, that there was some resentment from locals towards House as they perceived it to be adding insult to injury over the demolition of such homes in the area, and a crassness in exposing working-class abode for the ‘arty’ leisure classes. Yet, this wasn’t just a case of Art World vs. East Enders, the opinions were split within both camps: in the Art World, Andrew Graham-Dixon proclaimed it ‘a strange and fantastical object which also amounts to one of the most extraordinary and imaginative public sculptures created by an English artist this century.’ To Brian Sewell, it was a ‘meritless gigantism.’ Sewell’s scorn found resonance in one local’s assertion that ‘an engineer could have done it; I don’t see it as creative.’ Whereas, another neighbour to the site regarded it as ‘brilliant,’ reckoning it to be ‘a new way of looking at traditional things.’

House’s evicted resident, Mr Gale, protested, ‘They’re taking the wee-wee.’ He questioned, ‘How can they get grants for arts projects when we can’t get grants for homes? I could have bought a new home for my family with this money.’ His sentiment was echoed in graffiti scrawled on the sculpture: ‘WOT FOR?’ Another renegade scribe rebuffing ‘Why not!’

House’s economics became even more contentious when Whiteread won the £20,000 Turner Prize for the work (the first woman to receive the honour), and then £40,000 from the rebel K Foundation (composed of members of the defunct pop group KLF) for the ‘worst artist of the year.’ Whiteread split the latter money between Shelter, a charity for London’s homeless, and a fund to supplement young artists. On the same day, the Council made the decision to refuse House a stay of execution. By this time, many people (philanthropists, dealers, galleries) had offered to purchase House, but money offered to the Council to retain its presence was blasted by the authorities as ‘bribes.’ In any case, Whiteread was adamant that the sculpture was ‘absolutely specific to the site’ thus preferred its destruction to relocation.

The bulldozers came on January 11th 1994. The East London Advertiser reports that ‘art lovers’ chained themselves to the railings in attempt to save the work, quoting one as protesting, ‘We’re doing this because House represents the destruction of not only homes but whole communities in East London.’ Another suggested its removal was a sacrilegious act, perceiving House as ‘a headstone to the houses that were here.’ But the sculpture’s fate was sealed. As Whiteread succinctly mused ‘it took three and a half years to develop, four months to make, and thirty minutes to demolish.’

The legacy of Rachel Whiteread’s House

The Houseless Park has now had over 20 years to bed into the community’s psyche and flourish naturally. In all of the articles and art history books I have trawled to substantiate this article, House’s legacy is written off as a featureless Green with little footfall. As a local, I know this to be a fallacy: children play; peace-seekers read in the sun cocooned by the natural amphitheatre. However, I fear many are unaware of the political battle this site was home to.

House is still a succès de scandale in Art History, lumped with the other provocative creations of the YBAs in the early ‘90s – but lest we forget this was our House, E3. There is no blue plaque to House, like there is to the incendiary V-bomb, but next time you are at the Green look for the two simple benches close to the railings on the Grove Road side. As you tread the closely cropped grass, trace the silhouette – our fossil-monument to the East End vernacular.

If you liked this piece you may enjoy reading about local printmaker Ali Smith.

I really enjoyed this article. I remember House well and the controversy around it. Thanks.

Great article. I had no idea this is where that house stood.

You might like to know that the green, and Mile End Park in general, were actually planned in 1943, as part of the County of London Plan. These green spaces took time to realise because of the need to acquire the land by compulsory purchase. Weavers Fields was part of the plan too, although it was supposed to be bigger than it was.

Thanks for this article – so interesting to read more about the house, its making and history. I’ve lived in the area since 1981, and remember feeling excited to see House gradually emerging. It brought people to the area and made them think. I’m still amazed and sad that the Council swept it away so thoughtlessly.

Really enjoyed the article – I was always fascinated by House

I think the story behind the why and wherefores of House being demolished is controversial and, IMHO, sometimes becomes political. But if House hadn’t been demolished, would people be still talking about it today as possibly a great lost artwork of E3? Wouldn’t we have long since taken it for granted?

I am using your wonderful article for my thesis on public sculpture and artists’ moral rights. Thank you very much!

Hi Fiona,

That’s great to hear! Your thesis sounds fascinating. By the way – are you at UvA? I did a Masters there too!

– Anna

I watched the house emerge. I used to live round the corner on Antill Road, and in my mind it grew out of the shadows when I was still there, but if your article is right about the dates that was just my memory rewriting history, because I moved away in 1991. Mile End Park, before it was smartened up was a weird and wonderful mixture of the accidental, the wrongheaded and the well-intentioned. There was a pub by the canal which had been preserved as the corner of some long-demolished terraces where I used to drink occasionally. The House just beautifully summed up something about the surreal/unreal quality of the space and I was really sad when it went. Councillor Eric Flounders’ legacies to the area were generally negative.

The Slave masters statue remain and Rachel’s work is gone. 6pm Friday outside the Geffrye museum. Challenge the Geffrye Museum rejection of the will of the people, to remove it to a proper historical context.