Richard Lubbock on life after meth and his relationship with his son

Mile End resident Richard Lubbock, 72, has garnered national attention as Britain’s milder, altogether more pleasant answer to Breaking Bad’s Walter White. His journey from coin dealer to meth dealer, and the redemption that followed, has been immortalised in his son’s book Breaking Dad. As the dust settles on another extraordinary chapter in Lubbock’s life, he speaks with us about coming out the closet, living in the East End, and why everyone could do with a bit of therapy.

The book documents Lubbock’s unlikely metamorphosis from the perspective of his son, James. Lubbock had been married for decades when he came out to his wife and son. He moved to Limehouse in East London, began a voyage of self-discovery on the clubbing scene, and developed a methamphetamine habit. Habit became business, and his arrest in 2009 made national headlines. The publication of his son’s book has thrown Lubbock back into the spotlight.

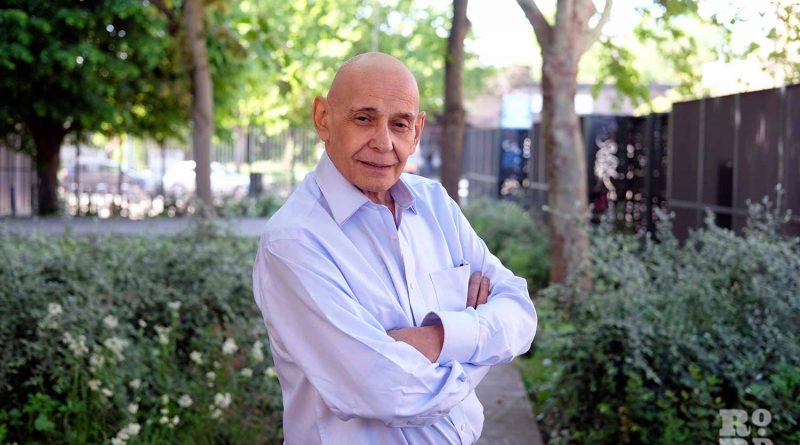

The fanfare seems to have taken Lubbock aback, a slight, lively man with a sharpness of mind that defies his age and recent history. Out of prison for five and half years, Lubbock has had ample time to digest his experiences and rebuild his life. Looking back on the events of the book, a stranger-than-fiction cocktail of sexuality, mental health, and drug abuse, he seems grateful for the chance to give them some closure.

Not unreasonably, the drug dealing has taken centre stage in much of the press surrounding Lubbock’s story. Methamphetamine is a highly addictive, highly damaging stimulant that became a household name with the success of Breaking Bad, in which the drug is central to the story. Meth use is not as prevalent in the UK as it is in other parts of the world, but it is on the rise.

To Lubbock the drug almost seems incidental, a consequence of unresolved issues surrounding his mental health and sexuality. He was a user first and a dealer second. After decades of repressed sexuality, it was a way to make him feel comfortable talking to people.

‘I never thought of myself as a drug dealer,’ he says. ‘I mean I know I was dealing drugs, that’s a ridiculous thing to say, but it was a social thing.’ Lubbock was 55 when he came out to his wife Marilyn, which was something he’d known about himself for decades.

It wasn’t until 2003 that Lubbock felt he could come out. ‘I was aware the mood had changed. It wasn’t such a terrible thing [as it was before]’ He certainly didn’t get the responses he was expecting. His friends laughed and said they’d known for years, and his then wife Marilyn went one better. ‘She was gay as well. I came out and told her, then she told me, and poor James had to be told by both.’ He says this somewhat sardonically, as if the irony has worn thin.

‘Funny isn’t it.’

The stigma hasn’t completely gone. Even today nearly half of LGBT+ millennials have not come out, a fact that can play out as isolation, depression, mood swings, or, in Lubbock’s case, selling meth. Coming out was liberating, but it couldn’t resolve decades of living a lie.

What should have been the most freeing period of Lubbock’s life became the most desperate. His physical condition deteriorated as his habit spiraled. Although spritely and clean cut today, he still wears the mark of meth on his fragile frame. James says his father is a step slower than he used to be.

It also wreaked havoc on Lubbock’s family life. He and his ex wife Marilyn initially maintained a friendly relationship, but when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer he missed the chance to join her and her partner on a final vacation. Such was the warped effect of his meth habit, he felt an obligation to be there for his clients. The low point was offering his son drugs, a memory that still disgusts him.

He characterises being arrested as a blessing.

And yet that period of his life served a purpose, if a warped one. ‘If only you saw me clubbing back in the early 2000s. I felt really strong. I mean I was nearly dead walking because I was so full of drugs, but I loved it. I can’t pretend I didn’t.’

He found a kind of ‘between worlds’ haven in East London. ‘You can do what you like here. I used to go to the opera and then go clubbing. That’s bizarre but it was great.’ He misses elements of those days, though not enough to go back to them. It was a release rather than a resolution.

There is shame in Lubbock’s past, but he is wary of compartmentalising his experiences as black and white. People are complex, and placing them in boxes does little to address the underlying issues. And what’s more, it isn’t realistic. ‘I’d have to have about 18 boxes to say who I am,’ he says, ‘but I think everyone’s like that really.’

Lubbock has attended 12 sessions with mental health charity Mind since being released from prison, and acknowledges resources for those struggling are improving, albeit slowly. People are learning to open up about things previous generations wouldn’t dream of acknowledging, let alone discussing. People think if they leave the problem alone, don’t look at it, it will go away.

‘That whole area is something they’re starting vaguely to understand now, government people and all that, though it will take them a lot longer yet. It is so crucial. If you’ve got people’s minds healthy in a country then they do a lot better.’

Although an intelligent man, Lubbock’s own father was a mercurial character. ‘The bad bits were really bad. There was no inbetween.’ He made a point of not passing on that experience to his son, but it still left his mark on him.

‘I think most people need a bit of therapy somewhere along the line because perfection doesn’t exist. You can’t have an idyllic childhood, no-one does.’

His time in prison, a period Lubbock characterises as a ‘rebirth’, confirmed his belief in the power of psychology. The forced proximity meant lots of interaction, and as Lubbock sobered up and rebuilt his strength he found himself acting as something of a father figure to other inmates.

Lubbock went to four different prisons during his sentence and his gentle personality made him popular wherever he went. Fellow inmates began to approach him, men laden with their own sins and their own demons, and open up about their experiences. ‘I felt like a father figure for the first time,’ he says.

This culminated in a series of motivational talks he gave to his wing’s football team during his stint in HM Prison Portland. After befriending by one of the team’s star players he was asked to talk to the team on the night before a game.

He stood before the semi-circle of players and asked them how they were feeling about tomorrow’s match. Everyone purported to feel fine, until the last guy, who said he’s feeling nervous.

Lubbock throws his head back as he laughs at this. ‘Finally we got someone to say the truth! And then I went into why they’re feeling nervous, into the principle that behind every fear there’s a wish.’

‘If you’re frightened of something it’s because you want to do it so much. It becomes a fear. The original feeling is that you want to win the game, but then you get nervous.’

The team won the game. And the next one. They went unbeaten for the rest of the season, with Lubbock becoming the de facto pep talk guy. Tactics weren’t his business (‘I’m still living in the days where there were outside rights and outside lefts.’); it was all about the mind.

‘They clicked onto that liked they’d understood it for years,’ he says. ‘Never let it be said that people who go to prison are stupid.’ The team won the last game of the season.

‘And that guy who actually said he was feeling nervous was heard to say afterwards, “He was inspiratirrronal!” ’ He rolls the the R with theatric relish. ‘That proved to me how important psychology is in everything.’

This has been proven again by his son James’ book, which Lubbock considers a triumph of self therapy. The press tour has been uncomfortable for Lubbock, but he has wanted to be there. Given the pain he has caused it’s the least he can do.

‘I’m not one for doing these things, I’m really not.’ he says. ‘Especially when it’s not exactly great publicity. But for my son’s sake I wanted to do it.’

Richard talks about his son with transparent pride and affection. He admires the courage necessary to not only look back on a difficult time, but to open oneself up to it.

‘That was a fantastic journey, an exercise in how to give yourself a therapy of your whole life. That is probably one of the greatest achievements anyone can do. It’s brilliant to read it.’

There’s a sense from Lubbock that his son succeeded where he failed. Lubbock was in therapy and analysis for 30 years starting when he was 19, and although he swears by the benefits there were elements of himself left unchecked. ‘My therapist would say we need to get the tears going, we need to get the tears going. That terrified me. I think I cried once in 30 years.’ Lubbock suspects this resistance contributed to his eventual slip into drugs.

‘Had I actually got to the deepest feelings I probably would never have got involved in drugs, but there you are.’

Lubbock has found an unlikely peace in life after prison. His son is married now with two children, girls, who Lubbock sees often and adores. He and his ex wife’s partner still go to the opera sometimes. Though it took time, friendships damaged by his arrest have been rebuilt.

‘Life’s not long enough for all this,’ he says. ‘When I was 20 there was no question of getting old or anything stupid like that, it wasn’t going to happen to me. Then suddenly, blink, and I’m old.’

Has he been tempted to pen his own book? To tell the full story? ‘It would be a great sequel in a way,’ he muses. ‘The period in jail I could probably write a book about it.’ But he shakes his head.

‘I can’t see myself doing it, even if I might want to do it. I’m sort of scared about doing it.’ He pauses, catching himself. ‘It’s the same thing! It’s because I want to do it myself the fear comes in.’

Breaking Dad is available to buy at Waterstones. If you enjoyed this article you may like reading about East End gent Eddie Brown’s mental health story

Really interesting story! Thoroughly enjoyed reading it. Great journalism again Fred!

I met you at The Verne, our sessions have stayed with me, I learnt so much from you and am delighted to know that your life is moving forward, positively, and that Opera is back in your life!