Historian Carolyn Clark: being Bow’s superwoman

Beneath Carolyn Clark’s gentle exterior lies an unstoppable force. Community historian, NHS researcher, newspaper editor, director of the Plastics Historical Society, deputy editor of the Plastiquarian journal, director of service and development at Crisis, Tai Chi instructor, humanist funeral celebrant, mastermind behind the East End Canal Festival – Clark’s list of achievements has reached legendary status in Bow.

Based in East London for 40 years, and Bow for the last 20, the common threads in Clark’s work have always been people and their experiences. As local heritage battles against demolition, indifference, and distortion, Clark now strives to preserve the myriad stories on which East London identity is built.

Forty years down the Roman

Clark’s relationship with Roman Road dates back to 1976 when, after a brief stint in Birmingham, she moved to Shoreditch. She soon became a regular. ‘I used to come up to the Roman when I lived in Bethnal Green and Shoreditch,’ she says. ‘I love my markets. Who doesn’t love a bargain?

‘You go down the Roman Road Market and I’m still impressed by the people you see down there who have been going there for years. They’re the ones who keep it going really. It’s still a real community centre.’

To Clark it’s one of the few East End markets that has endured in spirit and strength. ‘I still love the Roman Road. I find some wonderful things down there, I don’t understand why people knock it. I think it’s a good market. Three days a week is very rare in London. Very few markets do that.’

It has changed, in some places ebbed, but impermanence adds to the novelty for Clark. ‘That’s the beauty of markets. You lose sense of direction and place in them because you’re looking at the stalls rather than the things going on around you.’

Roman Road Market is very much Clark’s local nowadays. It’s been a long and busy road to get here. She worked in the NHS for almost 20 years, producing Public Health Annual Reports. She left the NHS in 1997 to become director of service at homeless charity Crisis. Three years later she moved to the Shoreditch Trust, a community-led regeneration agency, where she stayed until 2009. During her time there she developed a healthy living centre, which still operates today, and introduced a local bus service.

During that time Clark was edging east. Her husband, Jim, is from Bow, and 20 years ago they returned home. We’re talking in Clark’s living room-come-office, a neat turquoise space looking out onto Chisenhale Road out front, and the Hertford Union Canal behind.

Clark moved to Bethnal Green because she didn’t want to leave Shoreditch, then moved to Bow because she didn’t want to leave Bethnal Green. ‘I sort of edged along a mile at a time.’ She had her heart set on the street and they waited for it.

Living beside the canal was important to Clark. ‘I’ve always loved industrial landscapes,’ she says. ‘At the time people didn’t think much of it. Canals had a bad reputation of being smelly, dirty, and industrial, but from when I lived in Birmingham I knew it was fantastic.

‘There’s a lovely quote from about 1880 from a boatman, who would have lived on a boat, who said, “We live wi’ nature, and nature lives wi’ us.” Canals are that.’

Community development to community historian

Tidbits like that are typical of Clark’s connection with the East End. Oral histories have always been part of her work. From public health to homelessness to community development, people’s experiences have been just as important as the numbers.

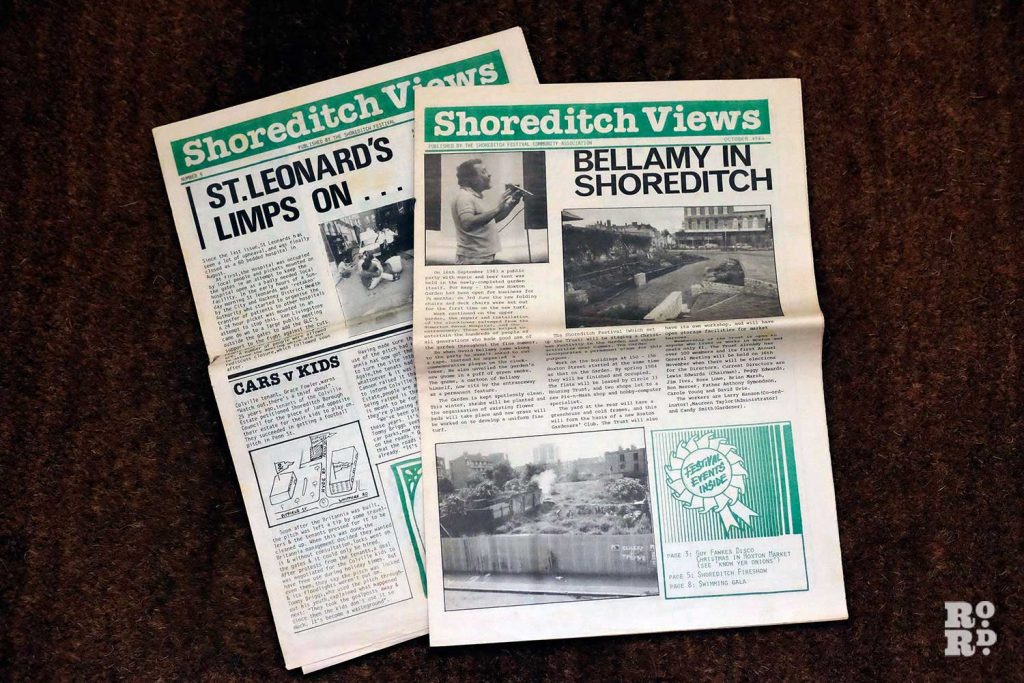

‘There’d always be stories,’ Clark recalls. ‘I just think people love stories, and I love stories, and it’s part of that process. You find out the factual stuff but you’d also have the stories to go with it.’ She started writing them down, working first as editor for Shoreditch Views, a community newspaper in the ‘80s, and later contributed a regular history column in Shoreditch Magazine.

Until recently she also worked as a humanist funeral celebrant. ‘In a way that’s the same thing, it’s telling people’s life stories.’ She had to drop it after historian commitments began to pile up, starting shortly after leaving the Shoreditch Trust in 2009.

While speaking to Laburnum Boat Club it became clear that local children didn’t know anything about the canals there were boating on. Clark successfully applied for a Heritage Lottery Fund grant in 2011 to research East London canals. The project snowballed and culminated in the East End Canal Festival.

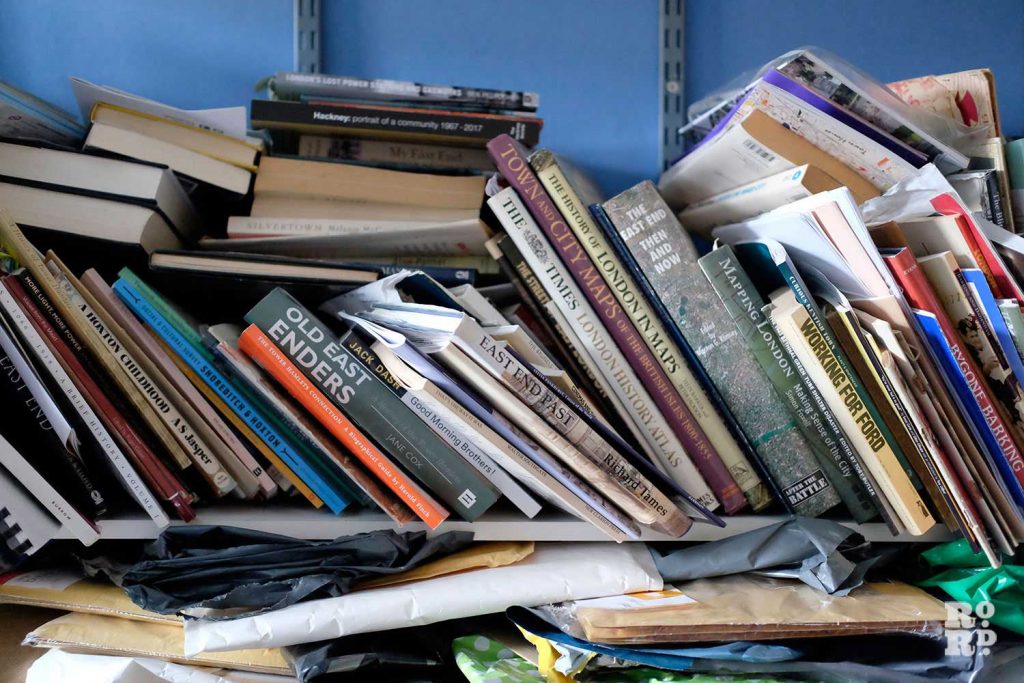

Since then Clark has written two books – The Shoreditch Tales with Linda Wilkinson and The Lower Clapton Tales on her own. She’s now working on a third book: The East End Canal Tales. Each book puts local stories front and centre, weaving together the experiences that make up London life.

Doing justice to an area is important to Clark, showing an inside view rather than one imposed by outsiders. ‘One of the things that motivated me originally was when I looked at what was available about the canals in terms of literature, it was all about West London. It was all about Camden and Regents Park, the pretty bits, and there were some really obnoxious comments.

‘You’d get artists who “discovered” East London, who’d say, ‘“When we first moved here there was a man and a dog and a pile of rubbish,” and it was the same with the canals. There were these guides saying, “When you go through Shoreditch it’s best to close your eyes until you reach Victoria Park.” Really rude.’

In response, Clark strives for the vibrant, unsanitized truth of East London, filling in the gaps of an area too busy working to document itself in real time. ‘I think it’s great to know what was where,’ she says.

And there are plenty to be found in East London. ‘The east is sort of dismissed, and in many ways it is far more interesting,’ she says. ‘Well, it was until they started demolishing every single building along the canal of any historic interest.’

Non-luxury flats

It’s fair to say Clark is fighting against the tide with her heritage work. ‘One of the beauties of London is its diversity of buildings, and we’re losing that diversity of buildings both with offices and houses.’ The booklet she made for the canal research project unearthed industrial heritage all along the Hertford Union Canal alone, a solid mile of factories, warehouses, and workshops. Now there are only a handful left.

‘In a few years’ time there’ll just be these nondescript places everywhere that are designed to be tall. Their main goal is to pack as much accomodation in the space as they can, build as tall as they can, to rake in the money without any sense of the space it’s in.

‘It’s not like people are being housed from the housing lists, because these developers seem to get away with promising a percentage of social housing and then not providing it. They seem to be allowed to do that, which I think is absolutely shocking.

‘Nobody builds non-luxury flats nowadays.’

To Clark it’s a case of killing the goose that laid the golden egg. ‘You think oh well it doesn’t matter, everything changes. And everything does change. But actually it does matter.’ Many of the stories unfolding today leave much to be desired.

‘It will be interesting to see what happens with Chisenhale Gallery down the road. The artists are in there, so it’s well used in terms of employment, which isn’t to be belittled, and the Dance Space is very successful as well. But they’re on a short lease and the building is pretty poor and needs money spent on it, so we will come to a state where there’s going to be a bit of a battle about that.’

The eternal jigsaw

Past and present merge in the life of Carolyn Clark. There’s no sign of her slowing down. She is currently working with the Young Actors Theatre to research the Islington stretch of Regent’s Canal, with a view to publish another booklet in time for the Angel Canal Festival this September. Beyond that she is already working towards the Regent’s Canal Festival, which is slated for 1 August, 2020, at the Mile End Ecology Pavilion.

Clark is also director of the Plastics Historical Society and assistant editor of the Plastiquarian journal. Her house is full of plastic items she has been collecting since she was a child. (She much preferred the plastic Easter eggs to the chocolate ones.)

She recently delivered a talk to the Raw Materials project at the Nunnery Gallery, sharing her knowledge of the history of plastics. As controversy around single-use plastics continue to reign, few are more frustrated by the frivolous, wasteful, and damaging misuse of plastic than Clark.

If that wasn’t enough, Clark also teaches Tai Chi twice a week, one at the Sonali Centre in Stepney, the other at St. Margaret’s House. She used to practice karate when she was younger. ‘It’s one of the big things I regret giving up, because you never retain that level of fitness again really once you’ve given it up.’

Fitness was a smidge more important than finesse. ‘I was not good at karate. In fact I was quite dangerous because I wasn’t good,’ Clark recalls laughing. ‘When you’re free fighting it’s really important to pull your punches and kicks, and if you’re not very good you’re not very good at doing that either. I used to draw blood a bit more than the others.’

The absurdity of it delights Clark. She’s a woman tuned in to life’s riches. She knows past, present, and future are all times defined by the people who live them, and preserving those experiences has always sat at the heart of her work. ‘I’m probably doing what I do now because it’s what I’ve always wanted to do, but every job I’ve ever done I’ve probably adjusted to suit what I wanted to do in the first place – secretly.’

And the process is neverending. ‘It’s always a jigsaw, the past, and finding the pieces is fantastic.’ With more stories to unearth, there are few safer hands than Clark’s to entrust them to.