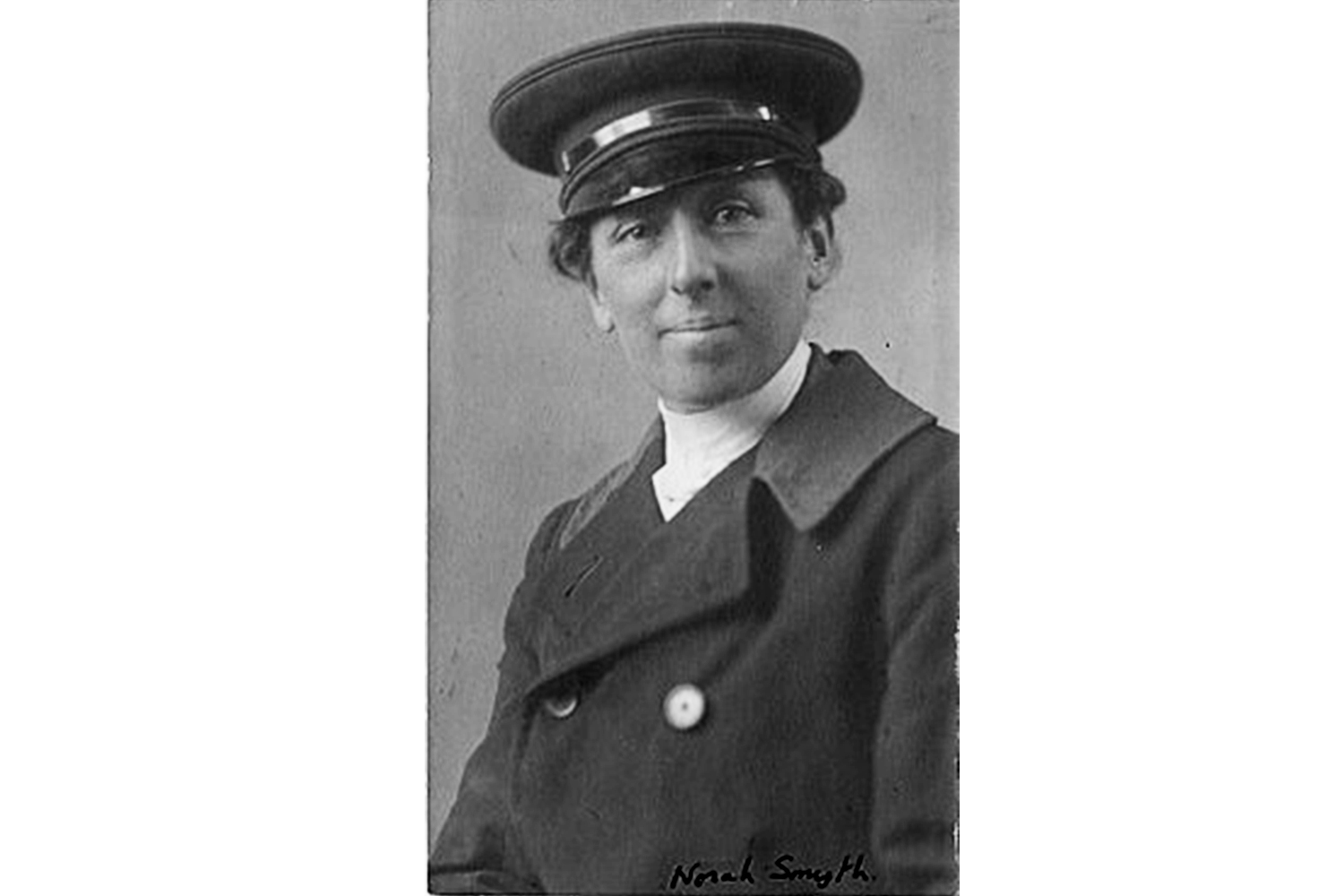

Norah Smyth: East End suffragette, photographer and chauffeur to Emmeline Pankhurst

Norah Lyle Smyth was a British suffragette, novelist, photographer and a socialist activist who worked alongside Sylvia Pankhurst on the suffrage movement in Bow, the heartland of the East London Federation of Suffragettes.

Smyth is well known for her close relationship with Sylvia Pankhurst, whom she accompanied and supported. Although she is one of the lesser known pioneers, she has not only dedicated her life to fighting for women’s rights, she also captured some of the key moments and figures in the history of women’s suffrage.

Smyth was born into a wealthy family, and was the niece of the composer and suffragette Ethel Smyth, the first female composer to be awarded a dame-hood in 1922.

Throughout her whole life and until his death in 1912, she was patronised by her father who controlled many aspects of her life, refusing her permission to attend university or marry her cousin, as she had hoped. Unable to gain higher education, she devoted her time to private study and the arts. Only after his death, she was able to leave her family home.

It is said that Smyth sometimes smoked a clay pipe and owned a pet monkey called Gnome. She also allegedly cut her own gravestone, with the date left blank.

In 1912, Smyth joined the Pioneer Players, Edith Craig’s feminist theatre company. It was around the time when she also started working as an unpaid chauffeur for Emmeline Pankhurst and joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). However, her greatest interest was in promoting the cause of working women, and this led her to join Sylvia Pankhurst’s East London Federation of Suffragettes.

The two became friends and began to work closely together on fighting to establish women’s rights. Smyth was very vocal about the ideas of feminism and showed great courage when planning revolutionary enterprises and joining bloody battles.

In 1912 she was involved in an arson attack on the country home of the vehemently anti women’s suffrage politician Lewis Harcourt. She managed to escape and leave the country, and only confided the story to her nephew many years later. She claimed the attack was on an empty part of the house to minimise risk to life and the art works it contained.

In 1914, Smyth established and led a group called ‘People’s Army’, undertaking a parade in Old Ford Road. ‘People’s Army’ also known as ‘Labour Army’ was a makeshift army designed to act as a form of protection from the police persecution of suffragettes. The army drilled every Tuesday night after the Bow Federation meetings. Drilling usually consisted of 80 to 100 people marching in formation, carrying clubs. The army was also supposed to defend free speech, drive out police spies and prevent wrongful arrest.

Its inaugural meeting was held at the Bow Baths where Sylvia Pankhurst was speaking. Three hundred mounted police turned up, furious that Pankhurst has escaped arrest despite the expiration of her Cat and Mouse license. Police officers tried to chase away people standing outside the Baths, but members of the army managed to dishorse some of the officers and drive the rest from the area. The next day, the triumphant army marched through Bow in celebration.

Two years later, East London Federation of the Suffragettes (ELFS) appointed Smyth its treasurer.

Although generally seen as a loyal supporter of Sylvia Pankhurst, Smyth was sometimes able to change her opinion; for example, she strongly advised her to remain active in the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom when Sylvia had been planning to resign. When the ELFS set up a toy factory on Norman Grove, Smyth was a strong supporter, and when in 1920 the factory was in financial difficulties, Smyth sold personal items to bail it out.

The ELSF also became involved in the Labour Party, and Smyth was elected to the Poplar Trades Council and Labour Party in 1919, alongside Melvina Walker and L. Watts. However, when the three appeared at a Labour Party meeting arguing in support of Bolshevism, they were expelled.

For many years, Smyth had used her photography skills to provide pictures for the newspaper of East End life, particularly of women and children living in poverty. She used her photographs for the ELFS weekly newspaper, The Woman’s Dreadnought. The name was ‘symbolic of the fact that the women who are fighting for freedom must fear nothing’.

Sylvia Pankhurst also appears in her photographs. One of them captures Pankhurst in 1913, recovering from hunger strike after her release from Holloway prison. Suffragettes were released to regain their health, then rearrested under the notorious ‘Cat and Mouse Act’, an Act that allowed for the early release of prisoners who were so weakened by hunger striking that they were at risk of death. They were to be recalled to prison once their health was recovered, where the process would begin again.

By the time some women finally gained the vote in 1918, the Russian Revolution had changed everything. The East London suffragettes were calling for international Socialism and trying to keep their vision of East End militancy alive. Yet political debates alongside financial hardships led to a dissemination of its members and the closure of the Dreadnought in 1924.

After a period in the Communist Party of Great Britain, Smyth followed Sylvia Pankhurst into a new, left communist, organisation, the Communist Workers’ Party. She was one of the leading speakers for the new party, alongside Pankhurst and A. Kingman.

When the party dissolved few years later, Smyth moved to Florence where she had family, and continued her adventures surviving a siege in Malta. Her and Pankhurst remained friends and stayed in contact until Pankhurst’s death in 1960. Smyth died three years later, in 1963.

Following the outbreak of WW1, the East London Federation of Suffragettes established clinics offering relief to mothers and babies affected by war poverty. The clinics provided free milk and eggs, as well as information on infant health.

With kind permission of Paul Isolani Smyth from the International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

Thank you so much for putting this up. I have lived in and loved the East End. It’s wonderful to hear these stories.