‘Black Widow’ Linda Calvey on the realities of East End gangster life

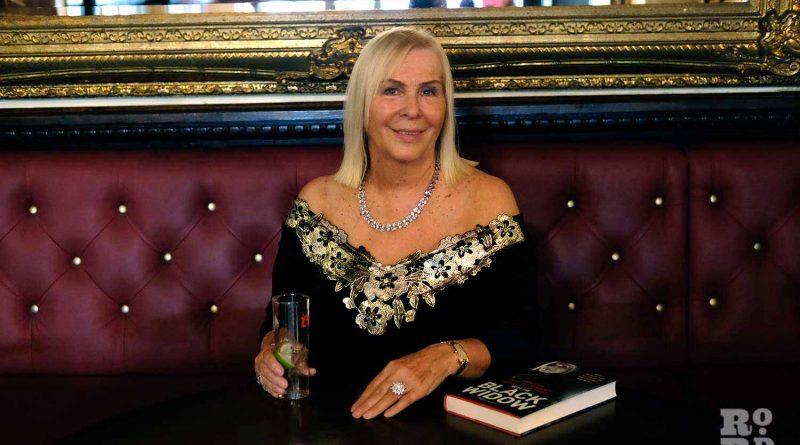

Flowery dress. Red toenails. Bleached blonde hair. Linda Calvey, 71, doesn’t exactly scream East London gangster when we meet on Roman Road, but most people would know better than to argue with her resume. She’s been a getaway driver and armed robber. Reggie Kray proposed to her once, though she told him not to be silly. Eleven years ago she completed an 18-year prison sentence for killing her partner, a charge she denies to this day.

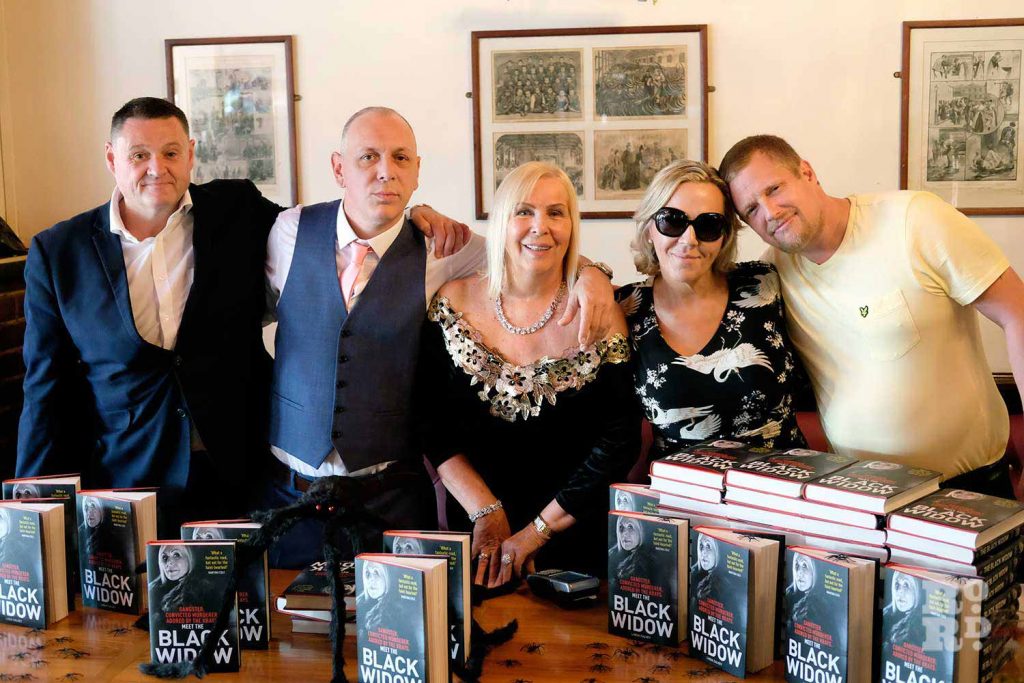

Calvey has written a book spanning her childhood in Stepney to the present day – The Black Widow. She has done so for two reasons. One, to take ownership of her own story, and two, to clear her name. Calvey owns up to all her crimes but one. She hopes by telling her own story she will inspire figures from her past to come forward and vindicate her.

You tend to get two extremes when talking with people about East London’s criminal underworld, neither quite complete. Some shrug it off as an irredeemable period of violence, poverty, and corruption, while others drift to romantic pictures of plucky, streetwise cockneys finding success in the only ways available to them.

Having gone from a loving childhood to bank robber to convict, Calvey has lived both sides of that world, and she wanted to give the full picture.

‘I didn’t want to sugar coat it,’ she says. ‘It’s not glamorous, it’s not wonderful. It’s terrible. While you’re doing these things you think it’s fantastic, but the flipside is a totally different story. When they say crime doesn’t pay, in 95% of cases it really doesn’t.’

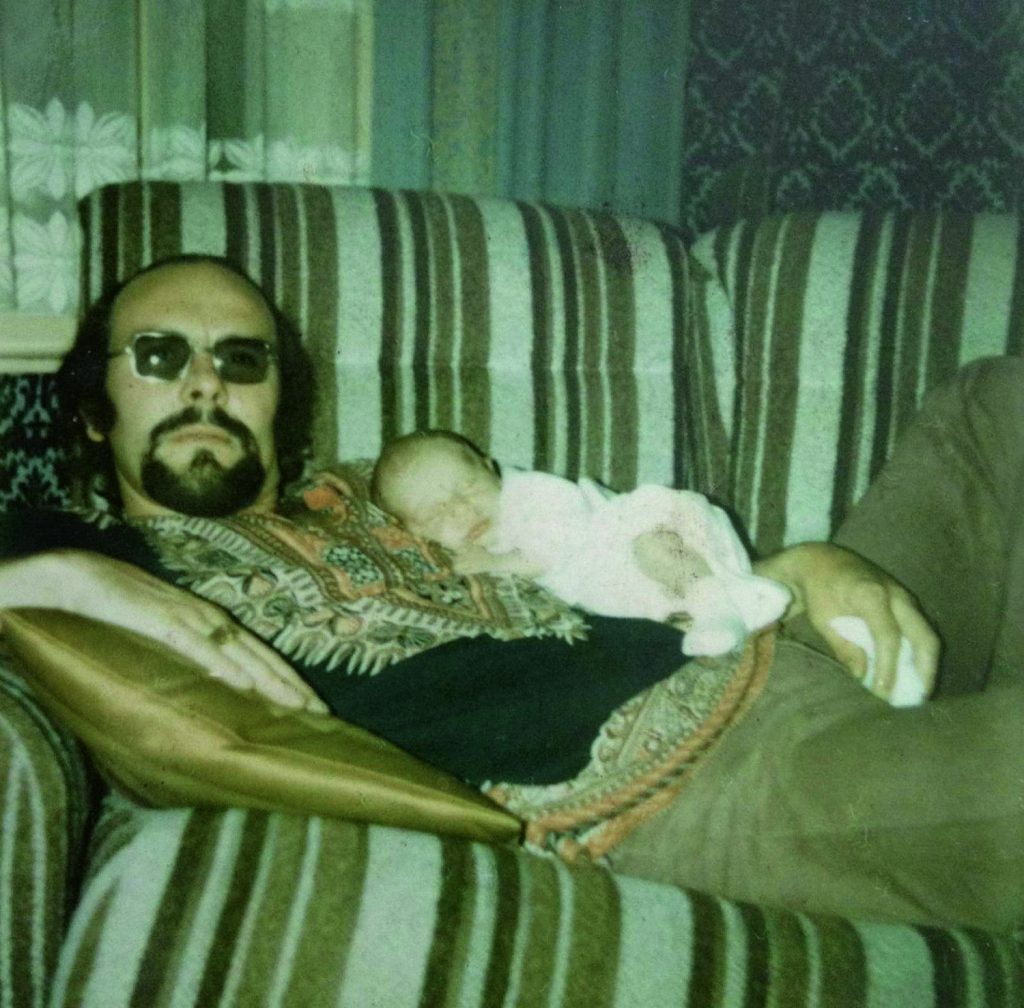

Two events loom large over Calvey’s past: the death of her first husband, Mickey Calvey, in 1978, and the murder of her then partner Ron Cook in 1990. The first tipped her into a life of crime, the second made her one of the UK’s longest serving female prisoners.

Mickey Calvey was shot in the back by a policeman during a botched robbery on 9 December, 1978. After a period of grief, his widow found herself behind the wheel as a getaway driver. Soon after that she was the one wielding a shotgun.

Looking back she can scarcely believe how it escalated so quickly. ‘I think I lost my brains a bit,’ she says. ‘I look back now and think how did I go out and do robberies? It’s really alien looking back now. I’m not saying it was post-traumatic stress, but there was something that happened in me that switched my brains around. I thought, right, I’m going to do that now.’

The terror she inflicted during that time hit home when she was finally caught. Staring down the barrel of a gun wasn’t all that pleasant for her either. She was sentenced to seven years and served three. Calvey’s unreservedly repentant about that time of her life. ‘I can’t justify it at all, what I did. I would never try to justify it.’

Calvey grew up in a loving household. Her mother ran a wig stall on Roman Road Market, and her father was a blacksmith who made dockers’ hooks. It was not until she fell in love with a bank robber that she began to see a rougher side to life, and even then it wasn’t immediately obvious.

‘Maybe because I was 19 I was quite impressionable,’ she says. ‘I thought, Oh, this is wonderful. I never looked past him coming in and putting money on the table and saying, Go on, get yourself what you want, get the kids what you want.’

Calvey was on the fringes of a bygone world, a world of armed robberies, protection rackets, and dumped bodies. It almost sounds cartoonish to Calvey as she remembers tricks of the trade – fake bus stops for would-be robbers to loiter by, fake workmen’s huts to store gear in.

And it had its glamorous side, the nightclubs and prestige and wealth. That’s what Calvey experienced to begin with. Working at her mother’s stall on Roman Road Market was more than work, it was a chance to flaunt status.

‘It was a bit like a fashion parade. All the girls used to get done up to the nines to walk down Roman Road. You look back now and you think, that was weird. Why did people get dressed up to go down the market?’ The hardened bustle of post-war East London underpinned Calvey’s early life. ‘I loved it. I like talking to people.’

She was a regular The Needle Gun on the road. (Vodka lime and soda, always.) The pub has since closed, though rumours persist that money was found under the floors when it was renovated. ‘I’m not surprised. A lot of the crooks went in The Needle Gun. I wonder if some of it was mine.’

She’s quick to restore the balance when these lighter memories come up. They were only one side of the story. ‘The other side is the horrible side where people end up doing years and years and years in prison, or dead. And it destroys families.’

Calvey sees parallels with youth today. While she came from a relatively well-to-do family, most in the criminal underworld did not, including Mickey. For them crime was the only way out. ‘I still do understand when youngsters look and think I’ve got nothing, why can’t I have this, I’ve got no chance of getting a good job, but I would say please, please think twice.’ Her own two children, Neil and Melanie, live life straight and narrow, and that’s just the way she likes it.

The second great upheaval of Calvey’s life is far less clear cut, and one of the main reasons for the book. In December 1990, her partner Ron Cook was shot and killed in their kitchen. She and Danny Reece were sentenced for the crime. The jury heard that Calvey had paid Reece £10,000 to do the deed, then fired the final shot herself when he lost his nerve.

Calvey insists otherwise. ‘On the day they treated me as I was – a witness to a murder,’ she recalls. On the day she did not ask for a solicitor. Police asked to do the tests, swabbing her hands and face. She remembers being given a white handkerchief with a blue initial and then being told they’d eliminated her as a suspect.

The next day she was charged. The tests had disappeared. Calvey obviously had previous with the police, chief of which was her insistence that Mickey’s death be investigated.

‘Instead of thinking, well it was her husband and she wanted to get to the truth, I think they was thinking, “That bitch, why didn’t she just sign our paper and this would all have been done and finished.” It’s gone back a long, long time.’

Cook’s murder is the one crime she does not own up to. ‘I’m hoping by bringing this book out it might prick a conscience.’

Whether it does or not, the book is a stark, unfiltered window into the underbelly of criminal life. If Calvey’s time in the East End crime circuit opened her eyes, her time in prison opened her mind.

She has shared prisons with Rosemary West and Myra Hyndly, even having to dye the latter’s hair for a time. She was the subject of proposals from Charlie Bronson and Reggie Kray. She married then divorced Danny Reece, the man who she claims really killed Ron Cook, a decision she has since recognised as PR faceplant. The lurid details have understandably been the focus of the press Calvey has received so far, but they’re not what seem to stand out to her.

It took Calvey going to prison to fully realise how good her upbringing had been. Many of her fellow inmates were young, aimless, and abandoned. ‘A lot of them had horrific stories. Broken homes, or they didn’t know who their dad was, or their mum was a junky and they was dumped from pillar to post. You could see what had happened to them.’

‘A lot of the youngsters in there felt more at home and safe in prison than they did outside, and I think what a sad thing that is.’

It shook her. They were criminals, yes, but many were also victims. As an elder stateswoman of sorts, they were drawn to her. Some of the girls called her mum (or ma when she was up north). Calvey’s own family was a huge help to her. Eighteen years in prison was no picnic, but it was tolerable.

If The Black Widow is successful she would like to do another book on prison stories. Good and bad. Having served with some of the UK’s most notorious murderers, Calvey is under no illusions as to some prisoners best being kept behind bars. As has been the case this time around, she simply wants to give an insider’s perspective.

In the meantime Calvey is enjoying her freedom. Out of prison for 11 years, she describes herself as a homebird now. She married for a third time in 2009, this time to George Ceasar. The Black Widow headlines duly rolled in when Ceasar passed away from cancer in 2015.

It’s all past now. Surreal, painful past. Calvey might not be able to believe she was part of it if not for bumping into the ‘old guard’ at fundraisers from time to time. They are veterans of sorts. They know. She crossed paths with Freddie Foreman recently. ‘When I had a picture done with him I went, Fred, do you regret meeting the Krays. He went, You bet your life!’

East London has changed massively since Calvey’s criminal heydey, and she’s pleased about it. She likes the evolution. It keeps things fresh. The current ‘yuppy invasion,’ as she calls it, only makes her laugh. ‘There’s nothing wrong with diversity at all, it’s nice. As long as everybody’s nice to each other that’s all you can ask for.’

There is a visible relief at her having finished the book. We may never know the full story, but Calvey has at least shared her side, and in her own voice. ‘It puts pay to all the speculation of what people thought or didn’t think.’ Could there be a final twist?

The Black Widow is available to buy on Amazon. If you enjoyed this article you may like our piece on East End gangster Freddie Foreman.