When Mahatma Gandhi stayed in Kingsley Hall in 1931

In 1931, Mahatma Gandhi came to London for the second Round Table conference, aiming to achieve independence for India, and he stayed in Kingsley Hall, Bromley-by-Bow.

Today, Kingsley Hall houses the Gandhi Foundation and has preserved a special cell room in its loft. This is the room where Gandhi lived from September to December of 1931.

Muriel Lester, who ran Kingsley Hall, befriended Gandhi when she visited India to learn about his social justice mission. While in India, she stayed at Gandhi’s ashram. When Gandhi decided to attend the second Round Table conference with the Indian National Congress, the British government offered to put him up in the Hilton Hotel.

Preferring to interact with the working-class people of London, he instead opted to stay in a small cell room in Kingsley Hall with Muriel. Accompanying him in London, his son Devdas Gandhi also stayed at Kingsley Hall.

The East End locals were excited by his arrival. In her pamphlet called Two Sisters and the Cockney Kids, Lylie Valentine wrote,

“When he arrived, I think all the people in East London waited outside to see him.”

Outside Kingsley Hall, Gandhi met the Pearly Queen and King of East London among many other locals, all eager to interact with the famous political ethicist.

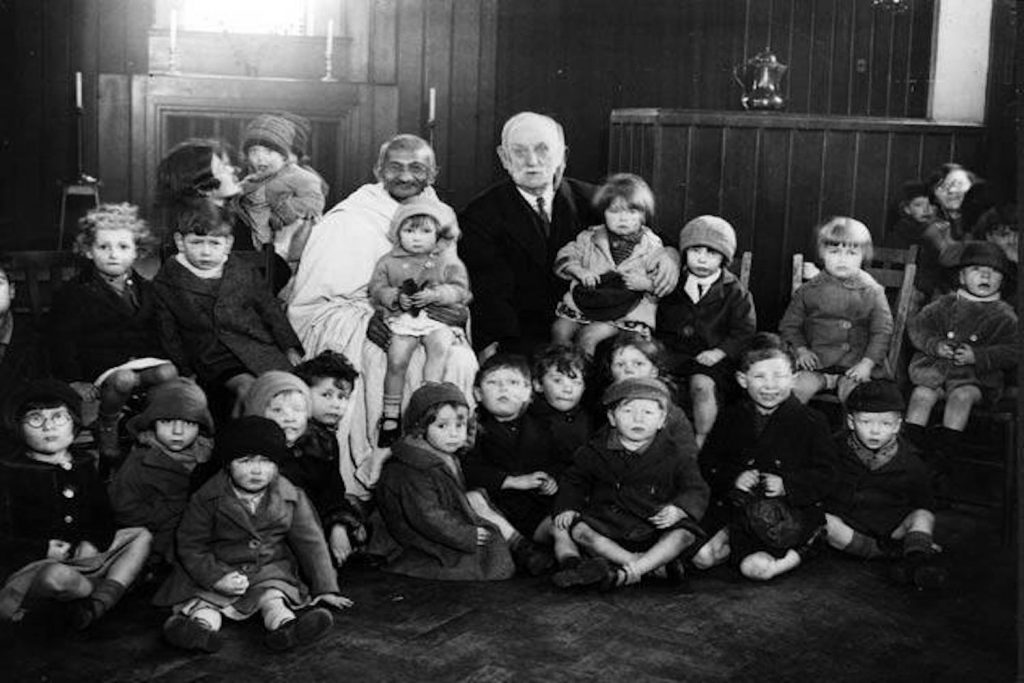

While staying at Kingsley Hall, Gandhi spent a lot of time interacting with Bow’s locals, many of whom were living in states of extreme poverty. On his daily morning walks, he would be accompanied by the children who were looked after by Kingsley Hall’s nursery.

On one of these walks, he was accompanied by the ten-year-old, William Saville who wrote an essay about Gandhi’s visit when he was still a child. His writing displays the intimacy that Gandhi experienced with the people of Bow during his stay. Saville describes,

‘He has given up all his belongings and is trying to be one of the poorest Indians. That is why he wears loin-cloth […] When he came visiting, he came to my house and my mother was ironing, but he said ‘Don’t stop for I have to do that myself,’ I have shaken hands with him.’

Saville’s juvenile writing provides us with a fascinating insight into how Gandhi spent his time in the East End, including his industrious fabric-making. Gandhi never travelled without his handloom and spinning wheel which he used to make the fabric for his own clothing.

While he was in the East End, he spent many hours at this craft. He weaved the fabric for his iconic dhoti which you can see in the picture above. A dhoti is a long loincloth that men in southern Asia traditionally wear.

There is an important context to such production. In colonial India, one of Britain’s main economic advantages was selling its manufactured cloth to Indian people. By underselling the village hand-spinning and weaving industry with cheaper cloth, Britain decimated India’s local economy. Gandhi’s clothing was therefore itself a protest against colonial rule.

On 20 October 1931, Gandhi gave a famous address to the people of Bow, outside Kingsley Hall, which he called ‘My Spiritual Message.’ In this speech, he said,

“I do dimly perceive that whilst everything around me is ever-changing, ever-dying, there is underlying all that change a living power that is changeless, that holds all together; that creates, dissolves, and recreates. That informing power of spirit is god.”

Whether religious, spiritual or neither, today’s East Ender can appreciate Gandhi’s sentiment. As iterations of the brutality of coloniality and classism pass by, an undercurrent of humanity in the people who protest them remains.

While we always have further to go—and the UK still exerts colonial exploitation on a large scale—decolonial and socialist movements are alive within the East End and the UK more broadly.

Though his intention to achieve Indian independence at the second Round Table Conference failed, Gandhi’s work with the poorest people in the East End should serve as a reminder that coloniality and class issues are interrelated and that our community should look after everybody in it.