Bow Porcelain Factory: the gruesome ingredient that changed the future of ceramics

The origins of the 18th-century Bow Porcelain Factory are shrouded in mystery, but archaeological excavations have unveiled the forgotten history of what was once England’s largest china manufacturer.

In 1744, on the banks of the River Lea and a stone’s throw away from Bow Church, an Irish artist and Bristol clothier began experimenting with porcelain production. By 1760, the experiment had paid off and Bow Porcelain was the largest factory in England. But how did it all begin?

In Bow, Thomas Frye and his partner Edward Heylyn found themselves a short distance from one of London’s oldest industrial sites, Three Mills Island, which had been milling grain and distilling gin from the 11th century. Surrounded by the spirit of East End entrepreneurship, perhaps the pair caught a fervour for novel modes of manufacturing.

At the time, China was the main producer of hard-paste porcelain and had been making the material since the seventh century. The porcelain was originally comprised of finely ground feldspathic rock and kaolin clay, fired at an extremely high temperature of 1400 °C.

Kaolin was the most vital ingredient, envied by other countries who lacked access to this valuable raw material. From the Middle Ages onwards, China’s porcelain was globally admired for its impermeability, whiteness and remarkable translucence, allowing light to pass through the vessel.

Countries couldn’t source the kaolin to produce ceramics of comparable beauty and durability, triggering huge demand across Europe in the 16th century for China’s costly ‘white gold’.

In 1710, the first European hard-paste porcelain was manufactured in Meissen, near Dresden. It wasn’t until December 1744 that England entered the industry when two Bow-based entrepreneurs began experimenting on the banks of the river Lea.

That winter, Frye and Heylyn filed their first patent for the production of porcelain utilising not kaolin, but ‘uneka, the produce of the Chirokee nation in America’. The patent said:

‘At a considerable expense of time and money in trying experiments, [we have] applied ourselves to find out a method for the improvement of the English earthenware, and had at last invented and brought to perfection a new method of manufacturing a certain material, whereby a ware may be made of the same nature or kind, and equal to, if not exceeding in goodness & Beauty China, or porcelain ware imported from abroad.’

The Cherokee are a people indigenous to the American Southeast, and uneka is a Middle Cherokee word for ‘white’. It seems Heylyn’s mercantile background may have enabled him to source and import quantities of the clay 8,000 km across the Atlantic Ocean to Bow, in a valiant attempt to mimic the grandeur of Chinese porcelain.

Nevertheless, for all their optimism, there is little recorded evidence of much porcelain being made under this patent on the west side of the River Lea. In 1744, Frye and Heylyn may have thought uneka could rival Chinese kaolin, but it turns out the secret ingredient was far closer to home, and a bit more grisly: bone ash.

The year 1748 heralded a relocation across the river, and a new, if grotesque, money-making material for the enterprising duo.

That November, Fyre filed a patent for porcelain production on the northwest side of Stratford Highstreet, between Sugar House Lane and Marshgate Lane. This new-and-improved factory was conveniently located closer to Three Mills Island, the industrial site full of piggeries and slaughterhouses providing a ready-made supply of animal bones for the eager experimenters.

Ground-up cow bones may seem a far cry from the finished product of a dainty porcelain mannequin. Nevertheless, it turns out calcified animal bones were integral to Frye and Heylyn’s winning formula.

The business partners may have been unsuccessful in manufacturing hard-paste porcelain, but they found bone ash added strength to their soft-paste mixtures, and a pleasing, milky-white finish to their ceramic masterpieces.

Today, a rare Bow Porcelain peacock from 1758 is worth around £7,888.40, and a pair of 1755 pheasants sold for almost £20,000 in 2011. But what were the ceramics worth in the 18th century?

The first recorded Bow Porcelain Company invoice is dated February 1749, issued to a Miss Bruce for ‘8 Arguile cups and saucers; 2 pint Sprig’d Mugs and 6 handled Sprig’d cups’ for the sum of one pound, nineteen shillings and sixpence, or about £230.42 in today’s currency.

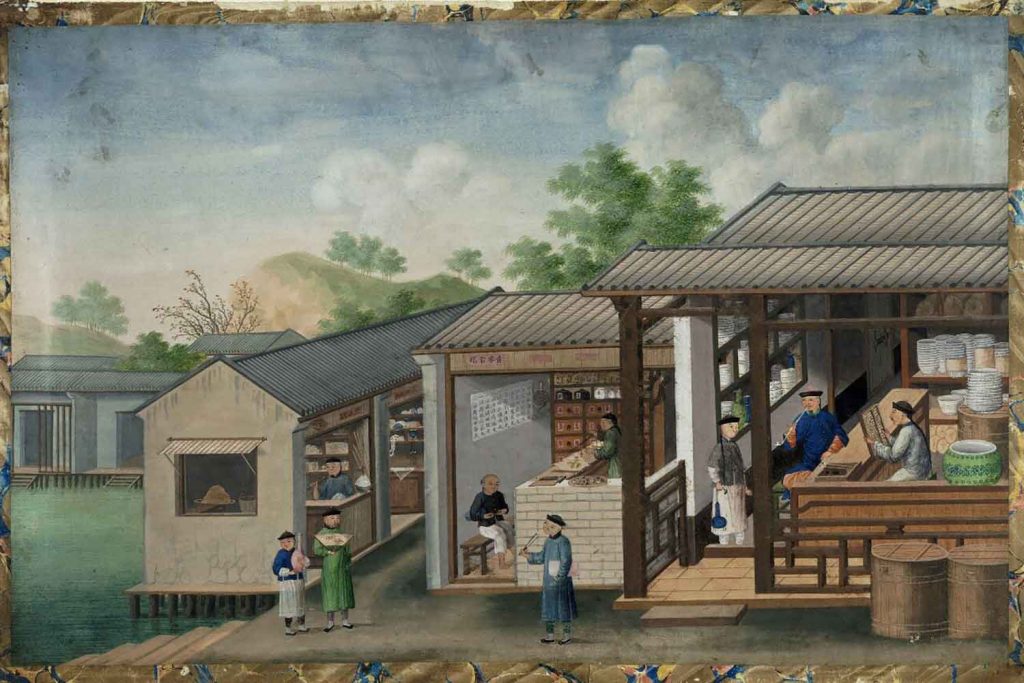

Like their first industrial site west of the River Lea, the Bow Porcelain Factory east of the river no longer exists. But in its heyday, Frye and Heylyn’s manufacturer was known as ‘New Canton’, rivalling the factories on the bank of the Pearl River in Guangzhou, China.

For years, the creative experiments of the East London entrepreneurs were overlooked, but excavations of the industrial site in 1867, 1921, 1969 and 2006 have shone a light on the unprecedented achievements of the Bow factory. By piecing together buried fragments of centuries-old china, archaeologists have salvaged the true extent of Frye and Helyn’s innovations.

By the end of the 18th century, the duo’s ingenious use of calcified bone ash to make ‘bone China’ was taken up by almost every other porcelain factory in the country. In its prime, the Bow Porcelain Factory employed around 300 hundred workers, 90 of whom were painters, all working under one roof.

Even in their heyday, Bow porcelain was not as celebrated as the cobalt blue-and-white masterpieces from China. The factory was notorious for manufacturing ceramics with an uneven finish, tending towards ivory as opposed to the pristine whiteness of Chelsea porcelain, a major competitor. Throughout the 1750s and 1760s, the factory directly copied Chinese, Japanese and Meissen designs, but couldn’t emulate their fine quality.

But the East London manufacturers were more than just imitators and were catering towards a different, more diverse market.

As well as meeting the demand of wealthy consumers, Bow Porcelain Factory produced an abundance of domestic wares for the middle classes on a more modest income. In this sense, the Bow manufacturers defined themselves against their more exclusive competitors in Chelsea, whose expensive wares were only enjoyed by royalty and elite collectors.

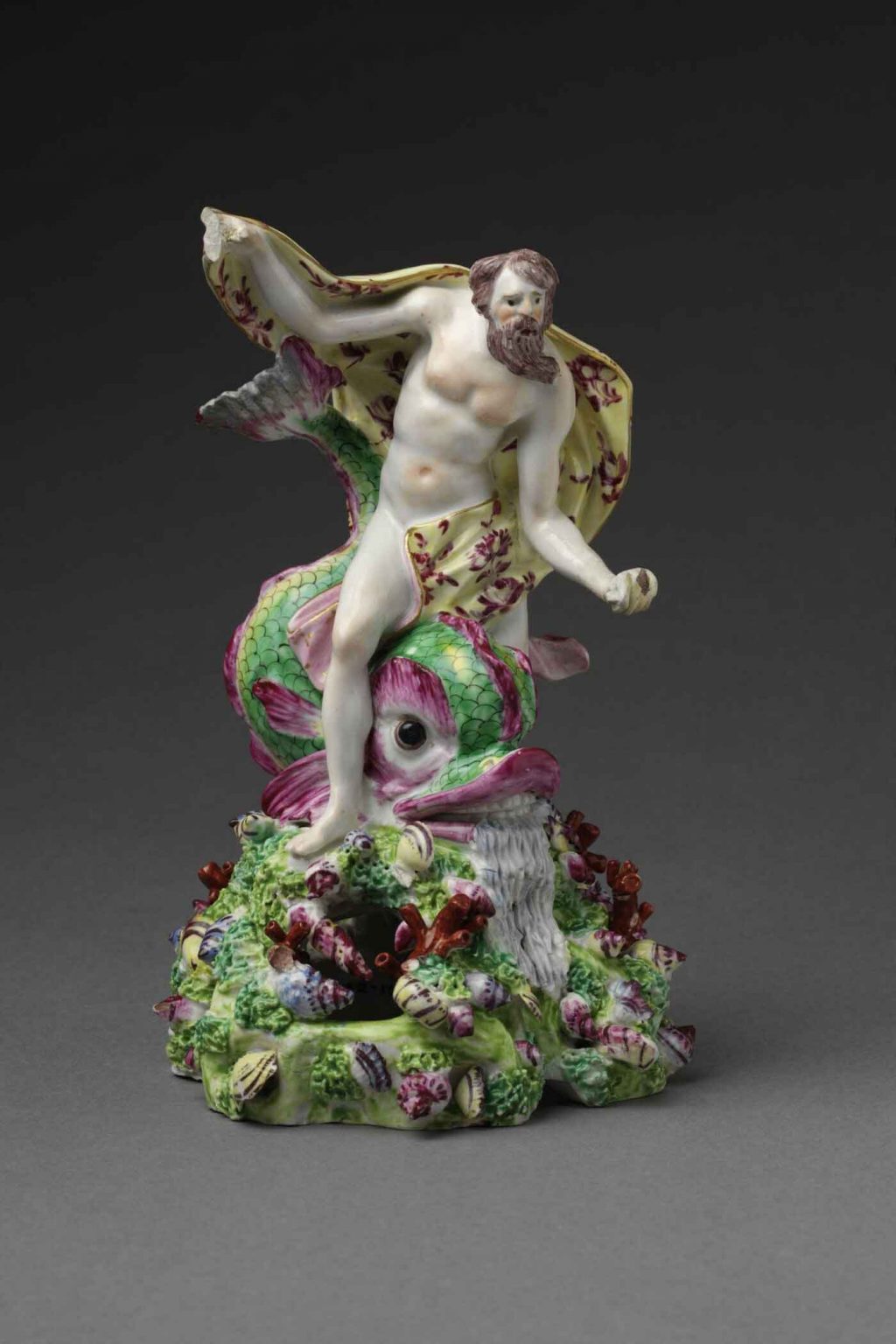

You could still rely on the Bow factory for decadent ceramics. Indeed, amongst their collection, you’ll find a majestic miniature Neptune astride a dolphin and an exotic lime-green parrot with intricate feathers. But by mimicking the prized elegance of the Chelsea factory without the price tag, the East London manufacturers allowed middle-class families a slice of luxury.

By 1750, the factory had passed into the new ownership of John Crowther and Weatherby, and Fyre was serving as manager. After booming in 1758, quality at the Bow Porcelain Factory declined and production decreased, and the company was eventually sold for a small sum in 1776.

While their success was short-lived, Thomas Frye and Edward Heylyn were an integral part of Britain’s global industrial legacy. Since the 20th century, countries worldwide have been producing bone china, utilising the ingenious method discovered by a pair of aspiring manufacturers in 18th-century East London.

With its inventive bone ash concoction, the Bow Porcelain Factory rivalled the celebrated majesty of Chinese porcelain from the banks of the River Lea.

If you enjoyed this article, you might like Something Smells a Bit Fishy! Jellied Eels: The Quintessential Cockney Cuisine.

Great article Imogen. The Bow factory holds a very important place in the history of British Ceramics. I hope the new V&A will seize the opportunity to showcase through exhibitions the arts and crafts, creative industries, architects and artists who have contributed so much to this area.

I inherited a piece handed down through my family which I was told is Bow Pottery, but local auctioneers/valuers etc all say they do not know enough to verify it (or otherwisde). Can Paul Miller suggest anyone in the Brighton or London areas who can do this?