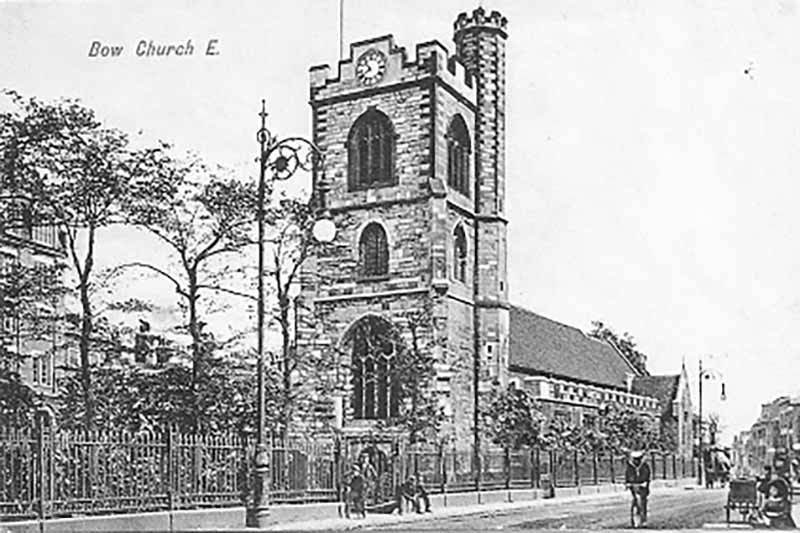

Blitzed and still standing: The beauty and endurance of the East End epitomised by Bow Church

Bow Church has been blitzed, its tower hit by storms and its bells destroyed, so how does it still stand today?

Walking down Bow road can make it hard to appreciate the beauty of the East End. Heavy goods vehicles roar past, cars outnumber pedestrians four-to-one and skyscrapers reign supreme over oak trees.

But as you step off the main road and into Bow Church’s gardens, the feeling of exposure evaporates. On this snowy winter’s day, frost glints in the sunlight, winter birds roost on its classical cupola and the last of autumn’s plants cling on to remind you of life’s beautiful yet transient state. The churchyard immediately has an opiate effect as you step into a scene befitting Victorian England.

No greater juxtaposition can be seen than between the Gothic architecture of Bow Church, with its iconic iron railings reinstated in 1984, and the looming mega-structures of nearby Stratford in the background. To think a nearby MacDonald’s is the more frequently visited building on this patch is bewildering. In the rush of life, it is easy to skip or miss out entirely on scenes that bring us closer to home.

Notice the statue of former Prime Minister William Gladstone that guards the church gates. His red right hand tells a story of protest, said to have been painted in 1988 to remind East Enders of the Match Girls Strike in 1888. That year, brave women and girls amassed in the churchyard to protest conditions at the Bryant and May Factory. It was rumoured a dock in their pay funded the statue, commissioned by the factory’s owner in 1882, leading workers to spill blood from their own hands on its base.

As you wander into the churchyard the hum of motor cars is somewhat muted, but constant. By the entrance still close to the main road, you can see a neo-classical memorial dedicated to Joseph Dawson, a lesser-known Bow philanthropist who dedicated his life to improving conditions for East Enders living in extreme poverty in the Victorian era. Dawson is only a feature of the churchyard, but an important figure in East End history nonetheless.

From this distance you can see the church tower that bears the ravages of time. In 1829 it was damaged by storms and misfortune struck again in 1896 when the chancel roof collapsed. If that was not enough, in 1941 a World Word Two blitz bomb destroyed the tower’s top half and the building’s west side. With the support of the community, a brick tower and a cupola in which the clock now rests was built in 1949. With a little help from its neighbours at Whitechapel Bell Foundry, Bow Church acquired new bells to remain a beacon of pride for the area.

Along the church path, welcoming benches sit on either side and delicate yew trees are interspersed to keep them company. To the left you can see gaps between a couple of yews. It was rumoured that just after they were planted the rector dug one up having left it late to get his own Christmas tree, and never returned or replaced it.

As you walk under the ivy-adorned arbor you approach the church’s chestnut brown doors. The buzz of traffic fades to nothing when you enter. Undistracted by the outside world, the stained glass window on the west side draws into sharp focus. It was installed after the blitz destroyed the original and features small animals, including mice, a cat and an owl portrayed in renaissance style.

Despite the fact that much of the upper tower was reconstructed, if you step outside and look at the lower part of the building you will find yourself gazing at medieval history. The tower has a 14th century Kentish ragstone base with Tudor additions and in that time Bow tradesmen chipped in to fund the church. This includes John of York, a baker, who left £14 4d to pay for candles and £3 towards a steeple, and carpenter John Laylond, who gave his stock of timber to make doors and floors of the new belfry.

Bow Church is one of East London’s oldest churches and has stood for over 700 years, with St Dunstan Church in Stepney the earliest built. During the reign of King Edward III in the 13th century, parishioners from Bow lobbied for their own chapel to avoid the slog to Stepney in harsh winter conditions. Now the last reminder of Bow village life and a haven among a booming metropolis, Bow Church stands as evidence of patient and tough East Enders who braved flood-hit roads to pay their dues at St Dunstan before wishes for their own chapel were granted.

As you near the exit towards the back of the church the gardens are less ordered. Scattered tombstones and creepers dominate as you step closer toward the alienating Stratford crossing where Bow Bridge once stood. Savour the last few steps of calm in this unlikely sanctuary that sits upon a traffic island created by the A11 dual carriageway.

From the parishioners who struggled to Stepney in the depths of winter, to the renewal efforts of Bow locals in the modern age, Bow Church represents East Enders’ action and pragmatism in the face of hardship. In particular, the aforementioned new west window with its animal drawings emblemises this, re-designed by architect H Lewis Curtis after World War II as a likely tribute to Arthur Broome, curate of Bow from 1820-24 and a founding member of what is now the RSPCA.

Small details such as the reconstructed stained glass window and upper tower remind us of our past struggle. But, just as they indicate an ordeal, these features demonstrate the stoicism of East Enders in surpassing these setbacks and acknowledging those who came before, rather than letting the church fall into disrepair. It is fitting that the church stands today from East Enders past who offered all that they had.

Read another of our heritage pieces on the world’s largest Victorian gasworks in Bromley-By-Bow.