Photographer Rehan Jamil on the changing faces of the East End

We talk to social photographer Rehan Jamil about his latest project exploring British and Muslim identities through the theme of food, and the importance of documenting the changing faces of East London.

In his 42 years, Jamil has borne witness to the shifting social dynamics of Tower Hamlets. First as a young man growing up in the Muslim community, and then as a photographer.

His latest project, which was created in conjunction with his creative partner Nurull Islam, founder of Mile End Community Project, is called Full English: a series of staged portraits exploring what it means to be Muslim and British in the East End, through food.

‘Full English is really a playful way of responding to all these claims in the media that you see about British Muslims not assimilating. But we do, and we do it our own way. We love a classic English breakfast. It’s just that for us, the meat has to be halal.’

Some portraits are particularly striking. There is one of a lady in a niqab, having afternoon tea at Victoria Park.

‘If you go to posh hotels that sell afternoon tea, it’s not unsual to see a lady in a hijab, or a Muslim man with a beard. We all like things that are traditionally ‘British’ or ‘English’ too’, he says.

These portraits showcase the diveristy within the Muslim community. There are people from different backgrounds represented – Somali, Bangladeshi and more.

The photos also show Muslims who practice their faith in different ways. There are portraits of people with headscarves, niqabs etc. And, there are those without. Portraits of men with religious beards, Islamic headwear, and those without.

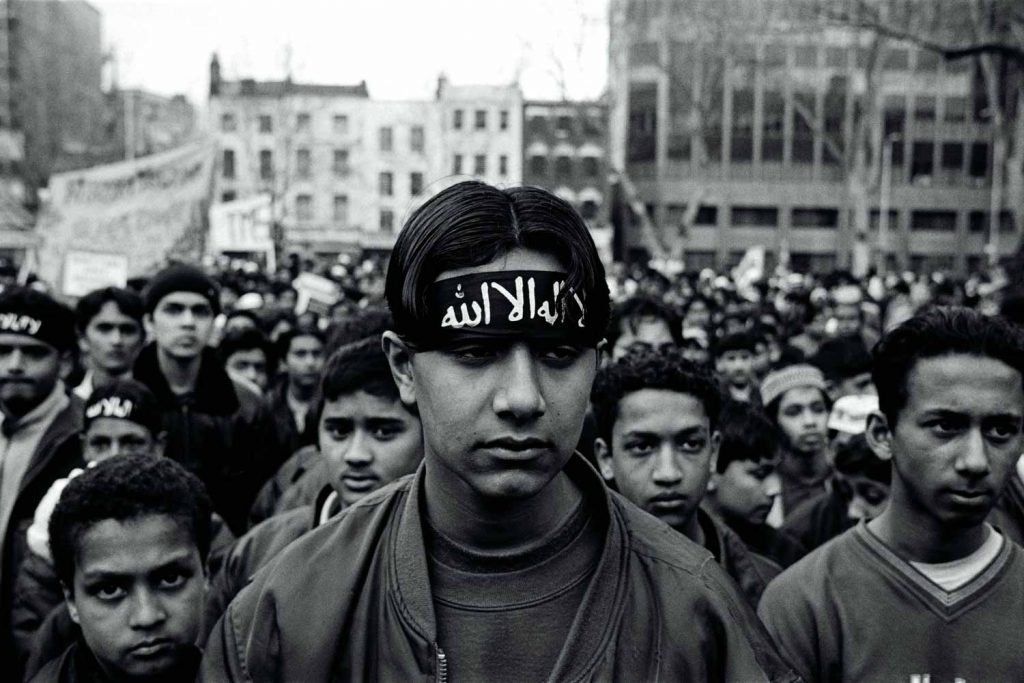

Grappling with questions of identity – who gets to be ‘English’ and who doesn’t – is an issue that Jamil could not avoid in his own life growing up as a young Muslim boy in the 80s, when Tower Hamlets was seeing the rise of violent, far right sentiment.

‘You had to be careful walking home from school because if you walk home late, you were at risk of being beaten up by gangs of men who were far right.

‘So if one of us had detention we would wait for each other so we could walk home together.’

The nineties arguably saw a shift in the Tower Hamlets Muslim community, with the successful application to extend the East London Mosque in Whitechapel into the London Muslim Centre. The centre was the subject of one of his earliest photo projects.

‘I wanted to show how mosques aren’t just a place of worship. They can also be a place for community.

‘I also wanted to show people who don’t regularly go to mosques what it is like inside. What goes on during prayers? Are women completely segregated? I wanted to shine a light for those who aren’t familiar with our culture.’

Around this time, he notes how the Muslim community gradually became more empowered in legislation, and better able to represent their interests within the local council.

‘It was around then you saw more of the market stalls being run by Muslims. From Bethnal Green market, stretching down to Roman Road Market.’

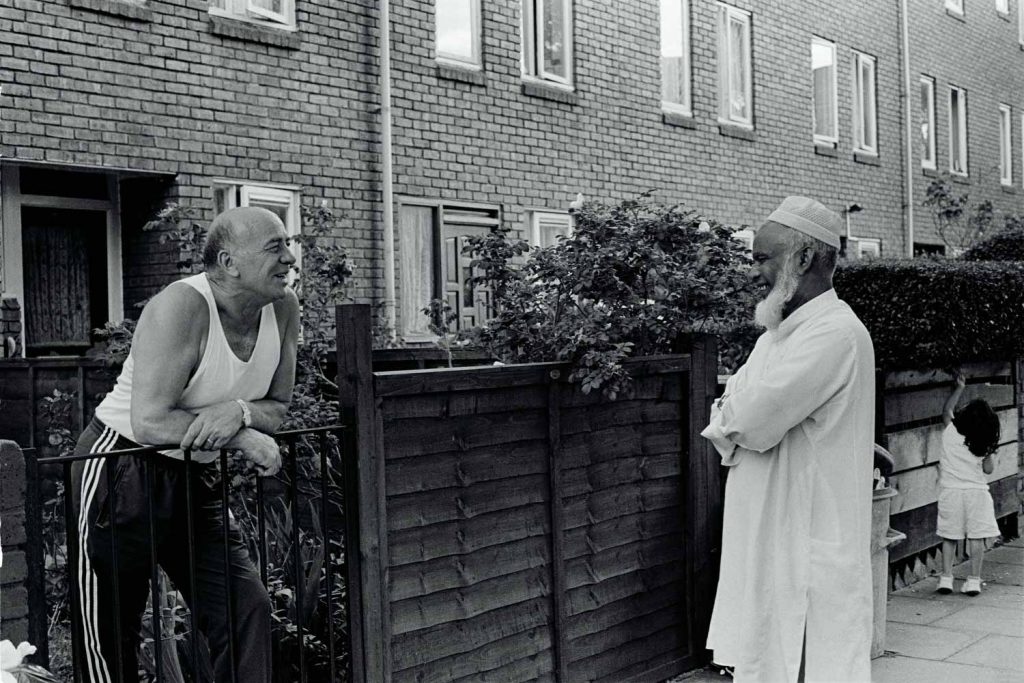

The rise and fall of communities in Tower Hamlets is a subject that generally interests him, extending beyond his own.

‘I’m interested in documenting communities in general. A friend of mine, an academic who researches into the Jewish community, said that years ago, there were dozens of synagogues in the area.

‘Now, he says there are four or five. Similarly, now there are about 50 mosques in Tower Hamlets. And East London is always changing. So maybe in the future, there’ll only be four or five mosques. That’s the nature of this place: waves of migrants who come and go.’

The worry of communities disappearing from Tower Hamlets led him to document people from all walks of life. He did a series, for instance, looking at the primarily white, working class council estate on Wager Street.

‘I talked to someone from there who said, “If I won the lottery, I would buy everyone their houses. So none of us would have to leave.”

‘If myself or you had won the lottery we might want to move somewhere nicer. But not them. They love their estates and they love their community.’

Now, Rehan is continuing his life’s work documenting the stories of those who have made the East End their home. His recent project is video-based, working with his creative partner Nurull Islam. They are recording immigrant families throughout the generations – from those who came here in the 20th century as citizens of the then-British Empire, to their children and grandchildren.