Camera as liberation: the founding of Four Corners and Camerawork

As Four Corners edges towards a full reopening, we glance back over its radical history, inextricable from that of the road it serves.

Founded in 1973 by four film students, Four Corners has long been one of the Roman’s important cultural institutions. A gallery, archive and film-making space, the organisation has played a key role in shaping the politics and practice of the UK film industry.

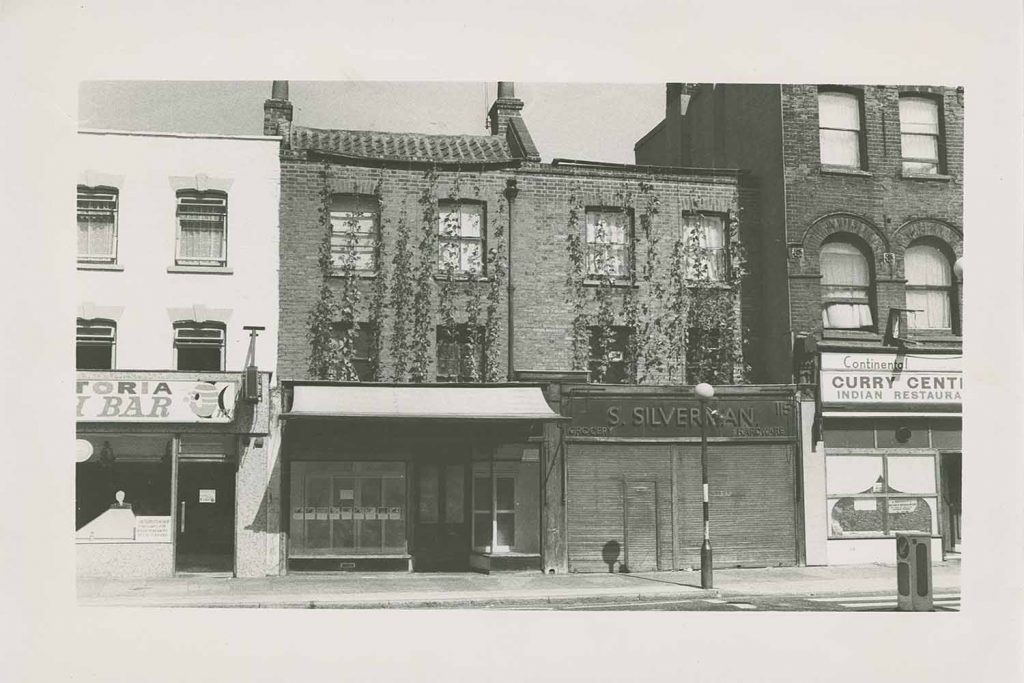

Today, Four Corners stands at 119-121 Roman Road, painted orange and plated in panels of galvanised steel. This elegant facade bears little resemblance to the organisation’s first home. As Ruby Rees-Sheridan, the centre’s current Curatorial and Archive Co-Ordinator explains, the founding members ‘began by squatting a greengrocer’s and a haberdashery’ at 113 Roman Road.

In the 1970s, the Roman was a very different place. It was a turbulent decade defined by oil shocks, widespread strikes, and the three-day working week. These national crises played out at local level, meaning the area often went without power or heat, and during the Winter of Discontent, rubbish piled high in the streets.

Back then the community was a diverse hotchpotch of ethnicities, religions and subcultures. ‘At that time it was a very working-class area,’ reflects Rees-Sheridan. Without smartphones, film remained an inaccessible medium to many. Cameras, projectors and editing suites were well beyond the budget of ordinary folk.

Expensive and technically complex, film was in danger of becoming a professional space reserved for ‘experts’ and the wealthy.

For many, this trend had deeply political implications. Thanks to the work of cultural critics like Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes and John Berger, the supposed ‘neutrality’ of the camera had come into question.

It was increasingly clear that the camera did not represent an ‘objective’ view of the world, but rather one that had been staged, framed and influenced by the filmmaker’s opinions and prejudices.

In this context, Four Corners offered East Enders the chance to represent themselves. ‘We aim to work with progressive groups,’ reads one of their posters from the 1970s, ‘in order to aid the representation of usually ignored, marginalised or misrepresented groups’.

At a time when there was no internet and only three TV channels to choose from, Four Corners played a key role in challenging dominant cultural representations. During the 1970s, lazy racist, classist and sexist stereotypes were commonplace. In the fight for equality, the camera was an important weapon in the arsenal.

To this end, Four Corners opened a cinema and production workshop, running screenings for local audiences. Expensive equipment and technical training was made widely available to the community.

At the same time, the Half Moon Photography Workshop (HMPW) was operating just a few doors down. ‘They were basically next door to each other on Roman Road,’ says Rees-Sheridan. Similarly innovative and workshop-based, the two collectives had shared aims.

‘The whole thing was about democratising photography,’ says Peter Kennard, an early member of the HMPW. As well as running exhibitions, workshops and darkrooms, the HMPW published Camerawork, a pioneering photography magazine.

In a statement published by Camerawork, the HMPW described itself as aiming to ‘demystify’ the photographic process. ‘We see this,’ the statement reads, ‘as part of the struggle to learn, to describe and share experiences and so contribute to the process by which we grow in capacity and power to control our own lives’.

In the wake of the British community arts movement, and the cultural revolution of 1968, many radical film collectives came into being. Cinema Action and the London Film-makers Co-op were forerunners, followed by the Berwick Street Collective, the Newsreel Collective, and Sankofa.

Following their Workshop Declaration of 1982, these co-ops flourished under the aegis of Channel 4. When funding dried up, however, lots of these organisations folded. How did Four Corners survive when so many others fizzled out?

‘Committed staff,’ says Rees-Sheridan, ‘and a big part is that we own our own building. That makes a huge difference in terms of not having to pay increasingly high rents in East London.’

In the early 2000s, Four Corners and Camerawork* merged. According to Rees-Sheridan, the group remains committed to ‘promoting accessibility film and photography’ to this day.

Following a £1m build project, the centre reopened in 2007. Today Four Corners runs exhibitions, offers co-working spaces, and provides members of the community with access to industry-standard film and photography facilities.

There is a focus on analogue filmmaking techniques; you can hire old film cameras and rent out the darkrooms which have been there since 1972. Today, when photographs are often throwaway units of communication, Four Corners offers locals the chance to explore the artistry and politics of the medium. “It’s a different way of working with images,” says Rees-Sheridan. “You can slow down”.

Over the years, Four Corners has mounted a series of important exhibitions in its gallery space. In 2019, they displayed Norah Smyth’s arresting photographs of the suffragettes, using history walks and panel discussions to explore the legacy of the East End’s suffragette movement.

More recently, Four Corners has been working on a three-year project called Brick Lane 1978: The Turning Point. Among other things, this campaign will explore the Bengali community’s response to Altab Ali’s racially motivated murder. Four Corners will display Paul Trevor’s photographs of the 1978 Brick Lane protests along with the oral testimonies of those who took part. As Rees-Sheridan points out, ‘there’s potential to reach a different audience’ with a window exhibition.

Infinitely adaptable, the centre has also been running a Zoom Film School throughout the Covid crisis. The course provides disadvantaged Tower Hamlets residents with free industry-standard film training.

These initiatives are just as crucial today as they were fifty years ago. Although the equipment was harder to come by in the ’70s, it was easier for film co-operatives to prosper in a lot of ways. ‘There was more arts funding around at the time,’ reflects Rees-Sheridan. ‘They got a combination of grants and access that doesn’t really exist in the same way today’.

Despite the digital revolution and access to video on mobile phones, today’s film industry remains the preserve of the wealthy and well-connected. Against this backdrop, Four Corners’ work is as vital as ever. In the words of Rees-Sheridan, ‘there’s still a lot more work to do’.

*In 1981, the HMPW renamed itself Camerawork, after its magazine.

If you enjoyed this article, you can explore the 2018 “Four Corners and Camerawork: Radical Visions” exhibition here.