Sir James Pennethorne: the story behind the architect of the ‘People’s Park’

Creating a park for the community: how Sir James Pennethorne, one London’s most revered architects, was given the role of developing and designing Victoria Park.

What do the bar in Somerset House, a road in east London and a community garden near Bonner gate all have in common? They all share the name of one of London’s prominent architects, who also happened to be the creative brain behind London’s first community park.

One of London’s green gems, Victoria Park, has a long history of uniting communities and bringing people together.

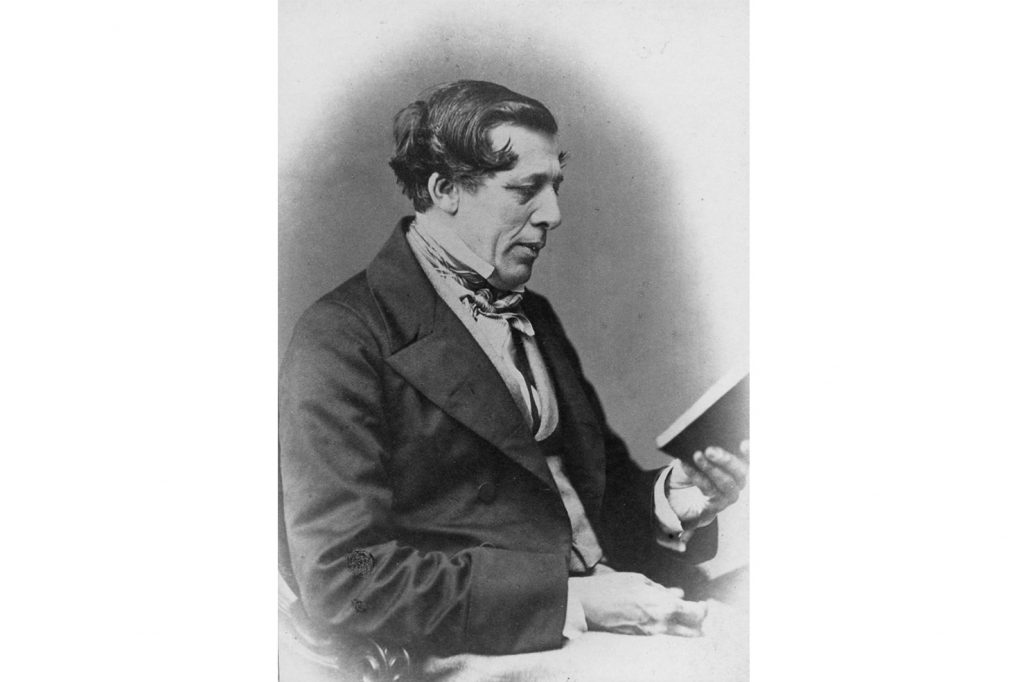

The government of the 1830s wanted to build a park in the East End of London to improve the health of the population and help stop the spread of diseases like cholera. They needed someone to bring their vision of the park to life, ideally, an architect they knew well and who had proved themselves to be capable of taking on ambitious design projects. The man for the job was James Pennethorne; a 40-year-old architect who was described as ‘quiet and conscientious’.

Pennethorne got his start throughout the 1830s designing grandiose manor houses for earls while training under the eminent city planner John Nash. Nash is best known for developing Royal estates including Regent’s Park and his support would have been an invaluable leg-up into London’s architectural elite for a young Pennethorne. Proving that nepotism was alive and well in the 19th century, Nash’s wife was Pennethorne’s second cousin, and the familial connection arguably couldn’t have hurt when Pennethorne enquired about becoming his principal assistant.

We tend to think of research connecting access to green spaces with improved mental health as a recent trend. However, it appears that the physical and mental health benefits of visiting parks were known more than 180 years ago, and it was thought that not only could frequenting a park improve your physical health but that they could potentially add years to your life. Around the same time as the report came out, a 30,000 strong petition from the local residents was sent to Queen Victoria demanding a green space for the East End of London. This only added to the mounting pressure to start work on the park.

Pennethorne’s talents came to the attention of the government, who appointed him as the architect and surveyor of the Commissioners of Woods and Forests, a government body charged with the management of Crown lands.

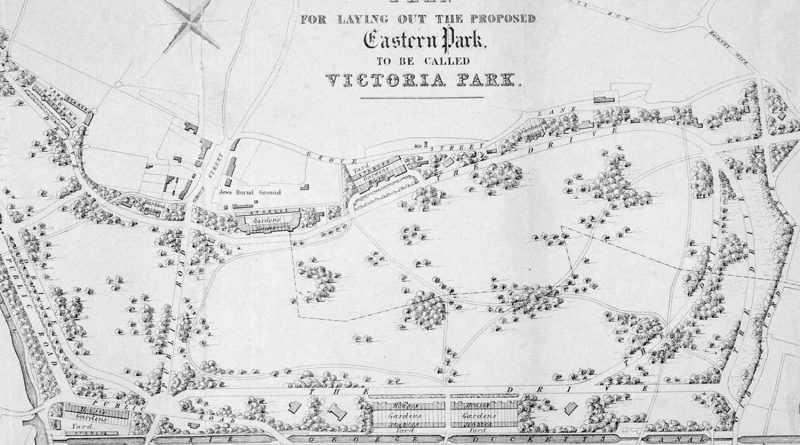

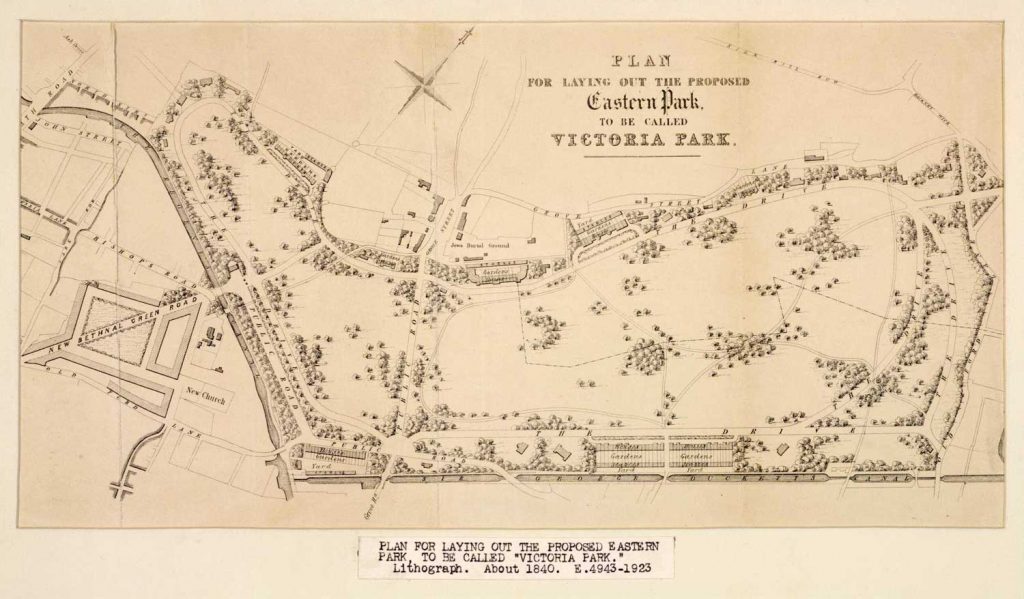

It was during this role that he came to work on the development for Victoria Park. His first designs for the park were drawn up in 1841 and included a grand archway, a pond for bathing and a landscape filled with greenery. His vision for the park included grand terraces on the perimeter, a superintendent’s lodge, and the pedestrian alcoves which had been bought over from London Bridge.

If you see a map of Pennthorne’s original designs for the park, you’ll notice how markedly different they are to the Victoria Park we enjoy today, with landmarks, such as the Pagoda and the Dogs of Alcibiades, introduced in 1847 and 1912 respectively.

It was officially opened in 1845 but the appetite for a green space in the East End meant that many people started visiting it from as early as 1843 when it was still under construction.

The park was created for the poorest people of the East End and was one of the first parks in London that was built specifically for the community. Locals would come to bathe in the ponds on a hot day, discuss politics at organised rallies and enjoy the first stretch of greenery in their area.

Although public health was a key reason for the park’s development, a less charitable reading of the reason for Victoria Park’s creation is that the park was intended to be a focal point for luxury housing to be built around. The plan to recoup the costs of the construction of the park through park-side terraced villas came to a halt when developers realised that not many people would want to buy a house that was situated next to a working canal.

Pennethorne was first and foremost employed by the government and likely didn’t take on the construction of the park as an act of benevolence towards the people of the East End. His later works included a wing of Somerset House (1849 – 1856), a ballroom at Buckingham Palace (1854), and King’s College London’s Maughn Library (1851- 1858). He was, arguably, not a salt of the earth architect for the masses, and taking on projects such as Victoria Park may have been vehicles to further his career rather than taken out of a sense of duty to the people of the East End.

However, his influence and expertise was key to the design of some of London’s most famous buildings, and to this date, he is one of the East End’s key planners and architects. Although Pennethorne died over 150 years ago, his architectural legacy lives on in the green spaces that millions of tourists and Londoners alike enjoy every year.

If you enjoyed reading this, then take a look at the story behind the Dogs of Alcibiades statues in Victoria Park.