When Fish Island powered Fleet Street – the story of John Kidd & Co ink works

The site of 419 Wick Lane on Fish Island was once home to John Kidd & Co, a printing ink manufacturer that shipped its products all over the world. Nestled on the bank of the River Lea in East London, Kidd & Co fed Fleet Street with the ink that made news possible. You could say it produced the original black gold.

Newspapers wouldn’t get very far without ink. Mythology surrounding Fleet Street tends to focus on the thunderous rumble of the presses, eye-watering expenses, and maverick upstarts speaking truth to power while nursing double vodkas. Although such characters make for a fun story (and aren’t without merit) the core idea of the newspaper remains beautifully simple: information printed on paper and made available to the masses. Writers, paper, and ink.

For nearly 200 years Fish Island was essential to that triad. At its zenith it was the beating heart of John Kidd & Co, and one of the world’s leading suppliers of printing ink. Little remains of the Riverside Works, whose workforce once boasted ‘a world-wide fame for the excellence of their production,’ but its legacy lives on.

Riverside Works

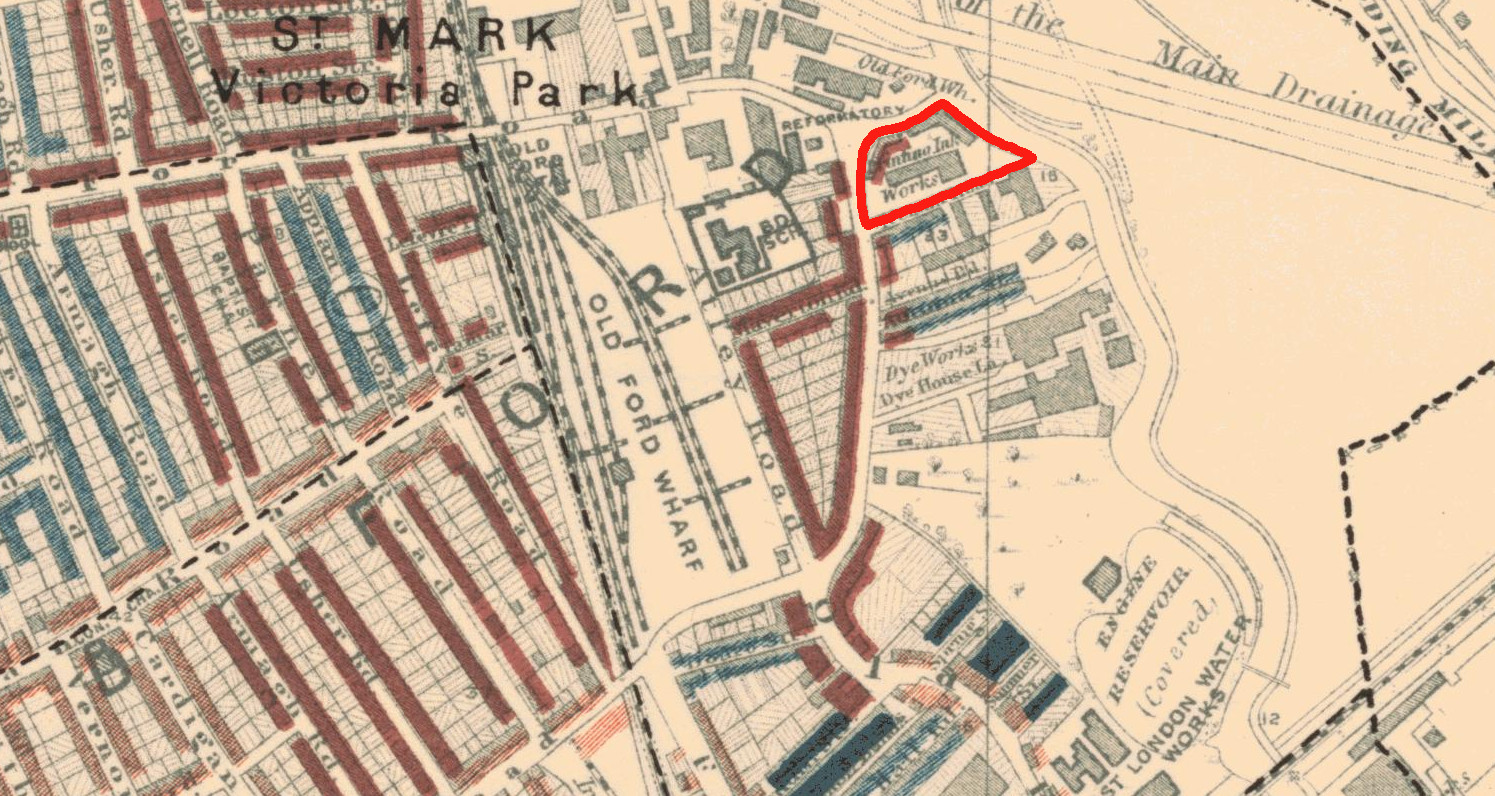

John Kidd & Co ink was produced at its Riverside Works, 419 Wick Lane. The site of the works was a dye works before being converted into a printing-inks works in 1765 by Benjamin Smith & Son. Smith & Son’s earliest printing related invoice is dated 1796.

Over the ensuing decades the works grew in means and in reputation. In 1862, the site was acquired by John Kidd. It was around this time that Dr James Sheridan Muspratt wrote that Smith & Son ‘have a world-wide fame for the excellence of their production.’

The steam powered, two acre site sat on the bank of the River Lea, a placement that made shipping simple. Barges shepherded goods straight to and from the Thames. Another perk of the location, in all likelihood, was it was handy for washing away some of the works’ dirtier produce.

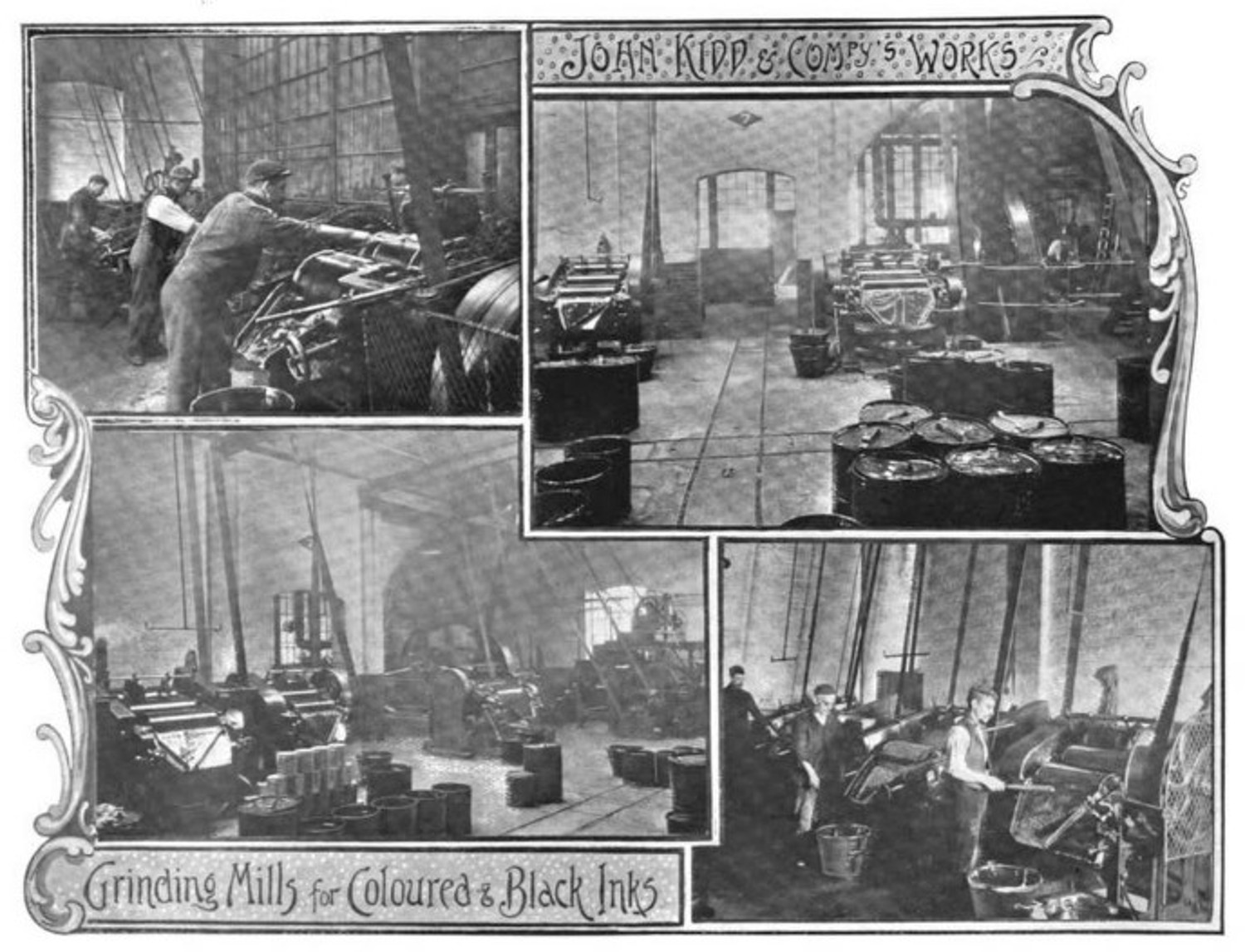

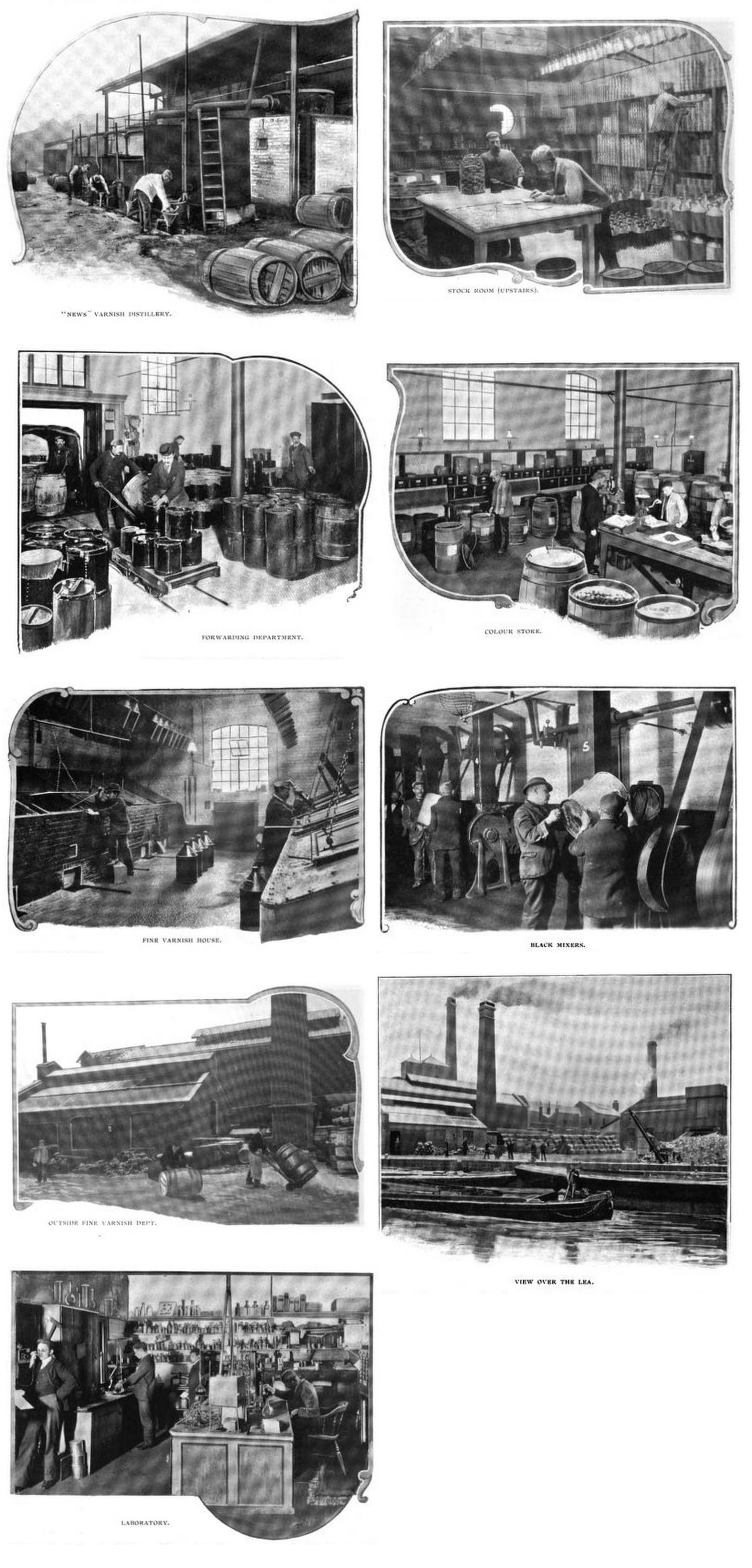

The clearest insight into life at the Riverside Works comes from an 1899 feature by The British Printer, a printing periodical. The publication was invited to have ‘a run around the works’ guided by ‘Mr. Percy Squire, the eminently practical and progressive managing director.’ They don’t make sentences like that anymore.

They also don’t make works like that described in the ensuing tour anymore. Passing through the steps of ink making, from varnish making to packing, the author describes a sprawling, meticulous centre of production. Vats hold 20 tons of varnish, others 30 tons of ink. One of the mixers is so large, even by the standards of Kidd & Co, that it has been nicknamed ‘Jumbo’.

At the tour’s conclusion, the author marvels at how ‘everything is up-to-date, cleanliness is studied and insisted on, and waste seems unknown.’ Although a feature about the guided tour of an advertiser should be taken with a grain of salt, the scale and efficiency of the old Riverside Works is obvious. The author notes that ‘neatness, cleanliness, and order are everywhere visible,’ and the accompanying images (shown below) support those observations.

Despite a rather unique potential for mess, Kidd & Co’s Riverside Works looked and operated more like a laboratory than a factory. During the British Printer tour the author observes that thousands of barrels are neatly stacked and numbered, waiting to be shipped to Hiogo, Otago, Melbourne, Demerara, Calcutta, Cochin, China, Madrid, and Buenos Ayers, amongst others. Kidd & Co imported raw linseed oil from Calcutta, and its ink was shipped all over the world. It was a truly global outfit.

At the time of the British Printer feature a number of Kidd’s clients received their entire ink supply from the Fish Island manufactury. The company produced several types of black, as well as around 300 colours, and newspaper ink was a flagship product. It’s not unlikely that the dispatches of journalistic titans like William Howard Russell were printed with Kidd & Co ink.

Inked

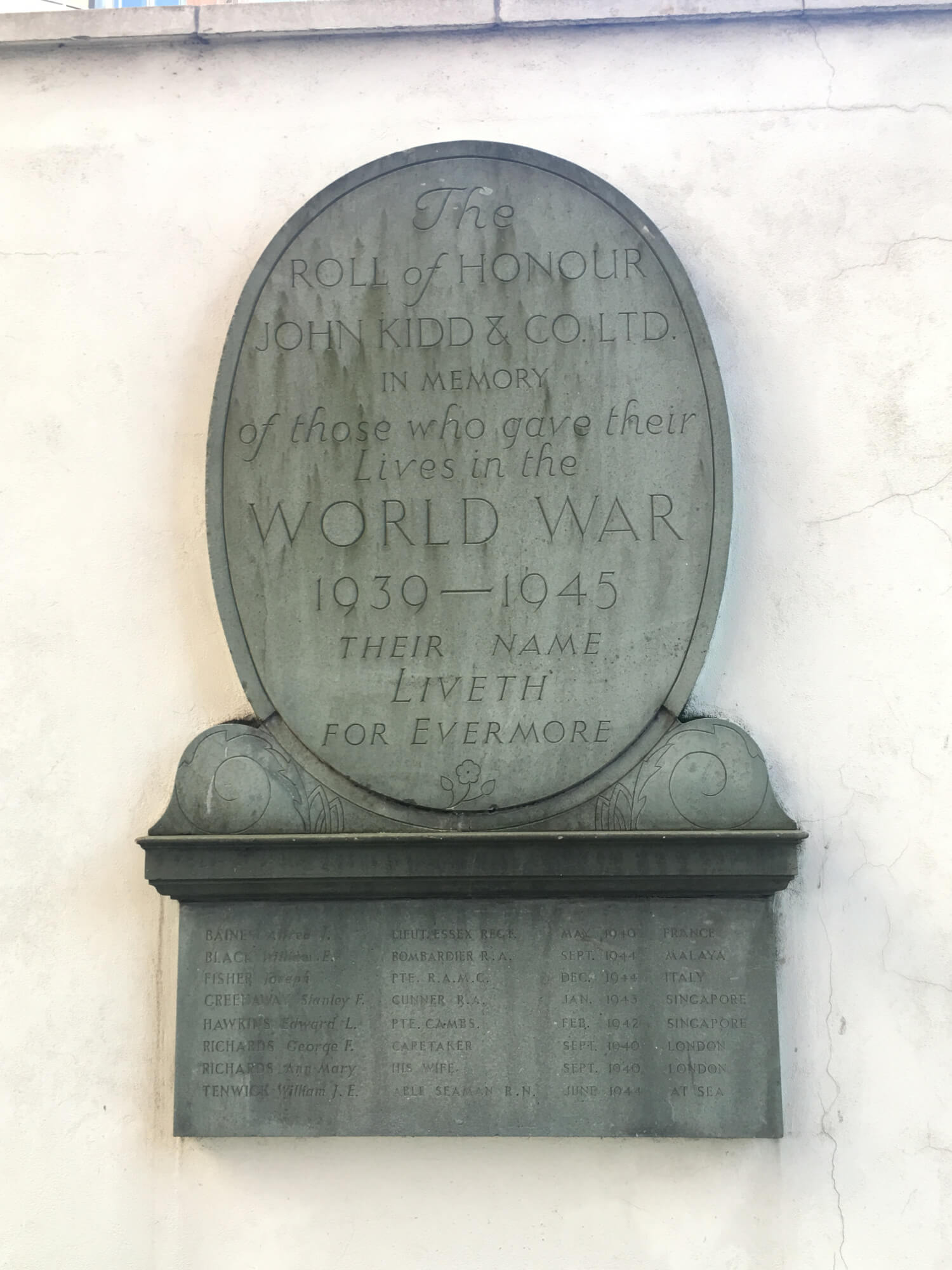

Kidd & Co merged with Mander Brothers in 1937 and continued until around 1952, when it folded. The site was then adapted as a furrier, before being vacated in 2003. An effort by local historian Tom Ridge to have the site listed was unsuccessful. The site was demolished in 2006 and replaced by flats, as is tradition. One of the buildings on the site is called Ink Court, in a nod to the old works. Aside from a World War II memorial plaque for its workers, practically nothing of Kidd & Co remains on Fish Island.

Appropriately, the Kidd & Co works made its lasting mark on the world with ink. Bold, vivid Kidd & Co ink advertisements – some well over a century old – remain a testament to the quality of its products. All these years later the colours still pop. A selection are shown below, and watermarked previews of others can be viewed at Alamy.

Newspapers have become a mainstay of modern life, but they wouldn’t have been possible without outfits like Kidd & Co. Like much of East London industry, its work was peripheral, thankless, and utterly essential. Where on earth would society be without ink?