Mile End Pogrom: the violent aftermath of the Battle of Cable Street

Amid a climate of record high antisemitic crimes, writer Siri Christiansen uncovers the history of the Mile End Pogrom. It is a story that uncovers how far right sentiment can go further in local and national politics than expected.

This article is part of a series by Siri Christiansen uncovering the history of the local Jewish community.

Many of us who live in the East End are familiar with the Battle of Cable Street, which is now commemorated on a mural near Shadwell. But less well documented is the Mile End Pogrom that took place a week after; it was a targeted, violent attack on the Jewish communities that spilled onto Grove Road, Roman Road and Victoria Park. It is acknowledged as being the worst case of antisemitism in interwar Britain.

On Sunday 4 October 1936, Londoners took to Cable Street to stop the Blackshirt fascist march through the heart of the East End, intended as the celebration of the fourth birthday of the British Union of Fascists (BUF).

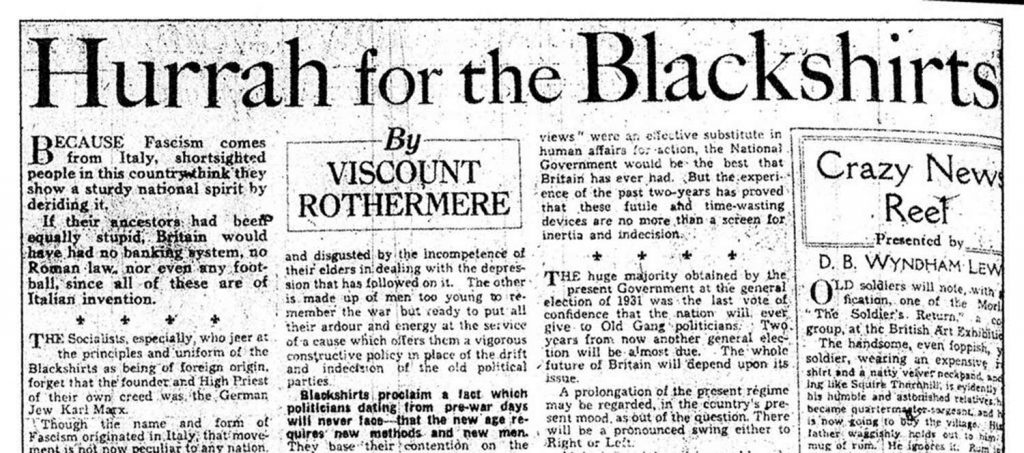

In those four years, the political party had grown to approximately 50,000 members and had even gathered some unlikely supporters, most notably the Suffragette Norah Elam and the Daily Mail, who published the headline “Hurrah for the Blackshirts!” in 1934.

The Great Depression had fuelled antisemitism among the aristocracy as much as in the working classes, but particularly in the deprived neighbourhoods of East End with its large Jewish community.

Jewish people in the UK were struck by a catch-22, blamed as much for being too poor and driving down labour costs as they were for being too rich, which is based on the antisemitic stereotype of exploitative landlords.

The BUF had a strong presence in the East End and had terrorised the neighbourhood for years by tapering the area with anti-semitic posters and graffiti, distributing antisemitic poems and leaflets, and terrorising Jewish residents.

But six months previous to the Blackshirts’ Cable Street march, the Jewish People’s Council against Fascism and antisemitism (JPC) had been established, and they were determined to stop the march

Together with the trade unions, the Independent Labour Party and the Labour League of Youths, the JPC urged locals to stop the fascist procession through the Jewish quarters. Tens of thousands of protesters showed up and held up the barricades against the 6,000 police that attempted to clear the area with excessive brutality. The fascist troops did not reach further into the East End than Tower Hill before they were forced back.

The Battle of Cable Street is remembered still to this day as a striking mobilisation against the rise of fascism in the years leading up to World War II; a turbulent day in which barricades were raised, bottles and bricks were thrown, and the fascists were defeated.

But the Battle of Cable Street was not the end of the war.

The BUF were quick to capitalise on the counter-violence by portraying themselves as innocent British citizens whose rights to lawful demonstrations were endangered by Jews and Communists. An estimated 2,000 new members were recruited soon after the Cable Street riot.

Only one week following the battle, Mile End would suffer the worst outbreak of antisemitic violence in inter-war Britain.

But the protestors were unaware of this coming terror. With roars of “They shall not pass” from the antifacist crowd at the Battle of Cable Street still lingering in the air, a peaceful antifascist demonstration to celebrate the victory was swiftly organised by the Ex-Servicemen’s Movement against Fascism and Antisemitism.

The next Saturday, on 10 October, an estimated ten thousand people gathered in Tower Hill to take back the streets that the Blackshirts had intended to march through, united under hundreds of banners carried by the Stepney Council for Peace and Democracy, the Dockers, the Furnishing Trades Association, the Communist Party and others.

But as they proceeded deeper and deeper into the heart of the East End, tension grew stronger between protestors and passers-by.

When the march turned onto Grove Road, hostile women and teenage girls lined up on the sidewalk, gesturing and screaming ‘the Yids, the Yids, we’ve got to get rid of the Yids’. At the corner of Bethnal Green and Roman Road, a double wall of police held back hundreds of young men and women shouting, ‘up the fascism, dirty Yids’. Under strict order to not let anything discredit the march, the protestors calmly replied ‘Mosley shall never pass’.

When the procession reached the gates of Victoria Park, the fascist youth had climbed onto parapets and railings. With one hand raised in the fascist salute, the other throwing bacon and rotten apples, chants of, ‘we are the boys of the bulldog breed’ were interspersed with the national anthem, each verse ending with the crowd spitting on the marchers.

By this point, after the march stopped in Victoria Park to deliver speeches and proceeded walking back to Tower Hill, the verbal abuse tipped over into physical violence. What began with fist fights quickly deteriorated into attacks on non-violent marchers as the fascists picked up weapons.

Two protestors had their faces and hands slashed with razors in Victoria Park; fireworks were thrown into the procession as they passed Roman Road. In Stepney Green, the fascists attacked protestors with iron weapons up to a foot long.

But the violent clashes only served as a decoy to occupy the police while the real attack was carried out. As police forces monitored the march towards Tower Hill, the fascists set out to destroy the local Jewish businesses. 150 fascist teenagers ran unimpeded down a deserted Clinton Road headed towards Mile End Road, smashing the windows and looting all the Jewish-owned shops in their way.

The sheer number of the fascists overwhelmed the shopkeepers, and the few who tried to stop them were attacked with stones and wooden planks. A Mr Samuel Jelen, who owned a hair salon on Mile End Road, was hurled through a shop window together with a four-year-old girl. Another Jewish man had his car flipped over and set ablaze.

The Jewish businesses in Mile End suffered financial losses and destruction of property as a result of the Mile End Pogrom, but the attack did not just affect the community financially.

As the culmination of years of ramped-up antisemitism in the neighbourhood, the incident made the Jewish people in the East End concerned over their safety in the area, as captured in the following interviews by a correspondent from the Jewish Chronicle shortly after the attack:

‘As I was speaking to one shopkeeper, his mother-in-law, who had just heard the news, rushed in. The look of terror on her face and her hysterical questions showed clearly that this attempt to terrorise the Jewish people of East London is having some effect. Another shopkeeper wanted to know what to do, and had decided to lay in a store of timber to barricade himself in against future attacks. […]’

Although these shopkeepers were naturally indignant at what had taken place, I noticed the apprehensive tone in their voices. One shopkeeper voiced this when he said, ‘I fear this is only the beginning.’

From our contemporary perspective , it’s difficult to picture the BUF taking power and turning the U.K into a fascist dictatorship. But in the 1930s, as one European country after the other was overthrown by fascists, it may have seemed like a real threat.

Italy was under Mussolini’s dictatorship, Germany had been overtaken by Hitler; one year prior to the attack, the Nuremberg Laws had stripped the German Jews of their basic rights; in July 1936, three months before the Mile End Pogrom, Spanish fascists rebelled against the far-left regime and threw the country into a civil war.

In the London County Council election five months after the Mile End Pogrom, the BUF polled 8,000 votes in Bethnal Green, Limehouse and Shoreditch, adding up to 19 per cent of the votes in some areas of Bethnal Green. While it didn’t suffice to win a seat, it was enough to fuel concerns over the growing support for fascism in Britain.

The Jewish community in the East End would suffer four more years as neighbours to a fascist party; four years of antisemitic posters, harrassment, fascist demonstrations, and a lingering fear that this may be the new normal. But with the start of World War II, the BUF’s close ties to Nazi Germany and Italy had them falling out of grace with much of their supporters before being banned by the government in 1940.

There’s a reason why the memory of the Battle of Cable Street has been detached from the counter violence it sparked merely one week later; it doesn’t fit into our narrative of what Britain is, what it represents, in particular during World War II. But with right-wing nationalism still present in modern times, it’s more important than ever to recognise our local fascist past; that it can – and did – happen right here in our own streets.

If you enjoy uncovering the hidden history of the Jewish community in your local area, why not read about the oldest Jewish cemetery in the UK that’s right on our doorstep?