Unearthing the oldest Jewish cemetery in the UK

In the second of an ongoing series mapping the hidden Jewish history in our area, local contributor Siri Christiansen takes a rare look at the Velho Cemetery in Mile End, the oldest Jewish cemetery in the UK.

It was while researching her Jewish ancestry that archivist and genealogist Imogen Rush came across the first ever Jewish cemetery in the U.K – the hidden Velho Cemetery, enclosed by brick walls, steel fences and locked gates just a stone’s throw off Mile End Road.

Together with members of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews’ Congregation, Rush has spent the past two years deciphering timeworn tombstones and matching them with the list of names, in order to create a map of the burials at the cemetery.

On a stormy Sunday morning, Queen Mary campus security opened the door to the cradle of the Jewish resettlement in England, and we ventured inside to unearth its remarkable history.

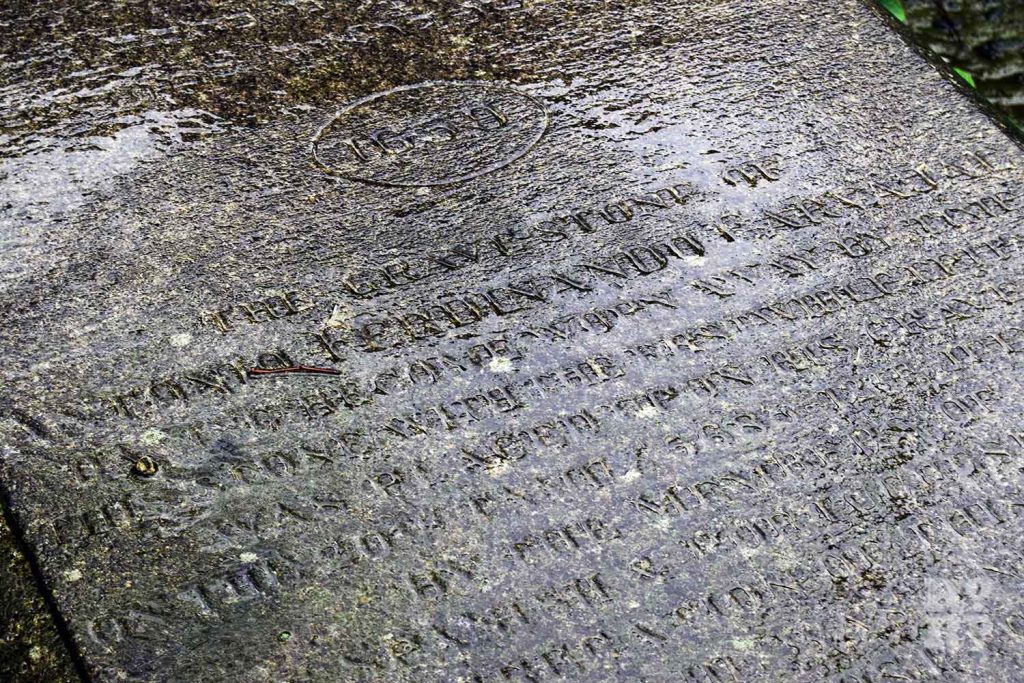

The trimmed grassfield in front of us is a vibrant green spliced with grey rectangles in symmetrical rows. Aligning with Sephardic Jewish tradition, the gravestones lie flat on the ground, their edges hugged by soft grass strands, raindrops gathering in faded trenches of forgotten names. We had picked a date to visit before looking at the weather forecast. I’m drenched; Imogen is thrilled.

‘This is actually the best kind of weather to visit the cemetery,’ she says, ‘because the gravestones are at their most legible when they’re wet.’

As we zigzag from one gravestone to the next, it becomes clear that Rush and I have a different understanding of what counts as ‘legible’. The Velho Cemetery opened in 1657 and reached its full capacity in 1733. The subsequent years have scratched off names, surnames, years of births and years of deaths on most of the graves, leaving behind silent blocks of stone. Making out the withered inscriptions requires skills, patience and knowledge of Portuguese, Spanish and Hebrew.

Rush’s involvement with the Velho Cemetery started out as a personal quest for the truth behind her family’s speculations of Jewish heritage. By consulting online resources made available by other hobby genealogists, she discovered that she had Jewish ancestry dating back to the 17th century. In hopes of tracking down their gravestones, she arranged a visit for her birthday.

‘Since I had read online that all the graves were blank, I was expecting to be disappointed. But I arrived after it had rained, and with the water pooled on the surface I could actually make out the inscriptions. I found all of my ancestors by the end of that day.’

Rush wipes the rain off her phone with her sleeve and scrolls through an app containing her family tree. ‘Let’s see where Sarah is… Sarah’s definitely buried here.’ After circling a group of gravestones in the middle-right end of the cemetery, Imogen recognises the grave of her eighth great-grandmother; Sarah, wife of Abraham Paz Morano, who died in 1717.

‘Can you read that?’ she asks. Without the aid of Rush’s finger outlining each letter, the bleary inscription reclines into the rugged stone, and Sarah fades away.

Much like its worn-down gravestones, the Velho Cemetery itself is strikingly anonymous. I search in vain for a sign or even a few letters, that can speak to an outsider of its historical significance. According to Google Maps, the cemetery is nothing but a grey unidentified square between a Qmotion Sport and Fitness Centre (the Queen Mary University gym) and a Wetherspoons.

While the Velho Cemetery is unknown to most Mile End locals, it is celebrated by the Jewish community in the East End and beyond as one of the most significant sites of Anglo-Jewish history. It marks the end of 366 years of Jewish expulsion in England and holds the men who put their own safety at risk to make it happen.

Following King Edward I’s expulsion of the Jews in 1290, Jewish people were banned from residing in England. This did not stop them from entering under disguise; a small community of Sephardic Jews, fleeing their persecution in Spain and Portugal, emerged in London in the 1630s.

Using their Spanish and Portuguese names and language to claim themselves as Spanish and Portuguese Christians, the Sephardic Jews managed to conceal their Jewish identity.

As successful merchants with international networks and large revenues, several members of the community rose to prominence and proved their value to their new country; Antonio Fernandes Carvajal (1590-1659), the first endenized English Jew who provided Oliver Cromwell with intelligencers who reported on Dutch and Spanish activities, and Simon de Caceres (d. 1709) was appointed as Cromwell’s advisor during the acquisition of Jamaica.

However, as war broke out between England and Spain in 1655, the Sephardic merchants found their disguise to be less favourable. As Spanish nationals, their ships and cargo were suddenly at risk of confiscation by the English authorities. When the merchant Antonio Rodrigues Robles was arrested on these grounds, he decided to protest the ruling by announcing himself as a Sephardic Jew who, due to Spain’s expulsion of the Jews in 1492, could not be considered a Spanish national.

The controversial case brought attention to the presence of the Jews in England and persuaded them to take action to secure their rights. In 1656, Antonio Fernandes Carvajal and Simon de Careces, together with other prominent members of the Sephardic community, revealed themselves as Jews by signing a petition to Oliver Cromwell asking for the right to practise their religion and bury their dead.

While Cromwell did not officially end the Jewish expulsion, he gave his word to Carvajal that their demands would be met, thereby appointing him as the principal agent of the English Jews. In 1657, he leased an orchard of fruit trees in Mile End for ten times its market value to establish the first Jewish cemetery in England.

Only two years after the Velho Cemetery was finished, Carvajal became one of the first people to be buried there. He would later be accompanied by influential contemporaries such as Dr. Fernando Mendes (d. 1724), royal physician and one of the first Jewish members of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, and David Nieto (1654-1728), an accomplished physician, astronomer and theologian who served as rabbi of Bevis Marks Synagogue and established the first Jewish orphanage in England. The gravestones of these prominent figures in history were restored with new headstones in the early 1900s to ensure their remembrance.

While Rush thinks that the Velho Cemetery should be more widely recognised for its importance to the establishment of the modern Anglo-Jewish community, she believes that the restricted access has been an advantageous measure in protecting the cemetery.

‘If you look at the Novo Cemetery, which is open to the public, there’s wrapping paper and plastic bottles lying around everywhere. This place shouldn’t be taken lightly and the fact that it is hidden is the reason it’s been preserved so well. It weighs up the fact that it’s unknown.’

Ever since Rush discovered the graves of her Jewish ancestors, she has been working with the Spanish and Portuguese Jews’ Congregation to commemorate the first generations of Jews in England and ensure that each and every one of them will be remembered.

‘After that first visit to the cemetery, the Chairman of the Disused Sephardic Cemeteries called me up and we started chatting about my discoveries. He told me about his idea to put up a map of the burials in the cemetery and I decided to help out.’

In the following two years, Rush has mapped out the over 1,500 burials at the Velho Cemetery as well as the roughly 1,700 burials at the Novo Cemetery around the corner. By cross-referencing the gravestones with the existing burial records, which lists burials in row order, Rush has managed to match the names of the buried with many of the illegible gravestones at the Velho Cemetery. Furthermore, her project has led to the discovery of new names that were never included in the original transcript.

‘Because stillbirth and children under the age of ten didn’t have gravestones and weren’t written down in the burial records before 1708, they’re essentially nameless. But recently, I have actually found several children’s gravestones.’

We walk up to one of the foot-sized graves. Following Rush’s finger, the only remaining record of a little boy who died in 1697 becomes visible: Moses, son of Isaac Rois Mogadouro.

‘No-one has known that this child is here since his parents buried him over 300 years ago. It’s a special feeling, being able to write his name down, telling the world: he’s here, this child is here!’

With the completion of the project, the map will be put up by the entrance to help future descendants locate their ancestors and connect to the past. In addition to this, Rush intends to publish the map on the website of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews’ Congregation.

‘Back when I was researching my own family history, the genealogy community helped me so much by publishing their findings online. This is my way of paying it forward.’

The Velho Cemetery is currently accessible to the public only with special permission from the Sephardic Jewish Congregation, which can be obtained by sending an email to velhocemetery@sephardi.org.uk

If you like this piece, you might also be interested in the reading about Novo Cemetery in Mile End.

I’ve just found using Ancestry that my 5th Greatgrandfather, Abraham Montefiore, was the Keeper of the Grounds for the Spanish & Portuguese Jewish Burial Ground (here) in the 1841 census.