The Novo Cemetery: a landmark of Jewish history hidden in plain sight

Local correspondent Siri Christiansen investigates The Novo Cemetery, a 287 year-old Sephardic Jewish cemetery in Mile End as part of a new series looking into the long history of the Jewish community in Tower Hamlets.

In the middle of the Queen Mary University campus lies the Novo Cemetery, now no longer in use and cut off from the outside world by the densely erected buildings surrounding it.

I carry my photographer on my shoulders as she tries to fit the cemetery into a single shot. Stretched out before us is the final resting place of over 2,000 people, frozen in time as fresh-faced freshers crisscross past each other in the narrow passages around the perimeter of the cemetery.

The Novo Cemetery is not just a reminder of our inevitable death, misplaced in a buzzing campus, but a site of immense historical value as one of two remaining Sephardic Jewish cemeteries in the U.K, for which it received a Grade II listing status in 2014.

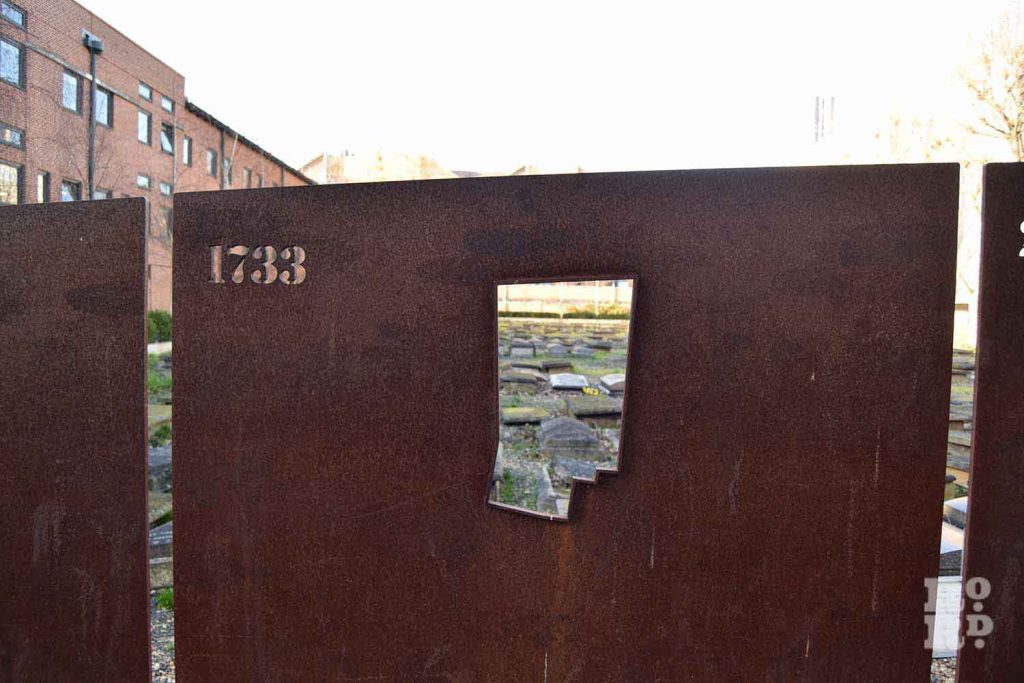

If we had visited about 100 years ago, the cemetery would not have been as easily concealed; the surviving fraction is only one fifth of its original five acres, where approximately 9,500 people were buried between 1733 and 1918.

There would have been a mortuary chapel by Mile End Road, and those who went inside could have glanced upon a plaque and tasted the first lines of its bittersweet inscription: ‘Rich and poor, the just and wicked, all as one’.

No verse could have been better suited for a Sephardic Jewish cemetery, an institution ruled by the principle of equality in death. The plaque is gone, as is the mortuary and 7,500 human remains, but looking out upon repetitive rows of stripped-down, horizontal gravestones, its egalitarian message still comes to mind.

Tracing the remains of the disused cemetery, one finds a compelling account of the first generations of Jews to be readmitted to England after their expulsion in 1290.

Faced with forced conversion, massacres and expulsion, the Sephardic Jews fled Spain and Portugal in the fifteenth century. By the end of the 1650s, around 35 Sephardic Jewish families were living in London in secret, and in 1656, a few brave members handed over a petition to Oliver Cromwell, demanding the right to practise their religion and bury their dead.

The following year, Velho Cemetery was built on a small plot of land in Mile End, marking the resettlement as the first Jewish cemetery in England. Now able to root themselves in London, the Jewish community grew roughly six times its size in the following 40 years, and the larger Novo Cemetery was ready in 1733 to put future generations to rest.

When first gazing out upon the Novo Cemetery, it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the number of laid-flat tombstones before you, nearly melting together in their uniformity. The design adheres to Sephardic tradition, where graves are kept unembellished as a reminder that we exit the world just as empty-handed as we enter it.

The rich variety of the headstones can only be distinguished when walking through the rows of graves. Many are shaped like rolled-out Torah scrolls and open books, arks of paper and doors. There are religious motives, such as the Star of David or the Cohen hands arranged for the Priestly Blessing, as well as decorative wreaths and flower arrangements. Other motifs are personal, giving some insight into the lives of the deceased. A tree cut down by an arm reaching out from the clouds, symbolising a life cut short.

The Novo Cemetery reflects a community in transition, as argued by Dr Caron Lipman in her book on the subject. Just as the Velho Cemetery marks the end of 400 years of Jewish expulsion in England, the Novo Cemetery marks the beginning of an integrated Anglo-Jewish community.

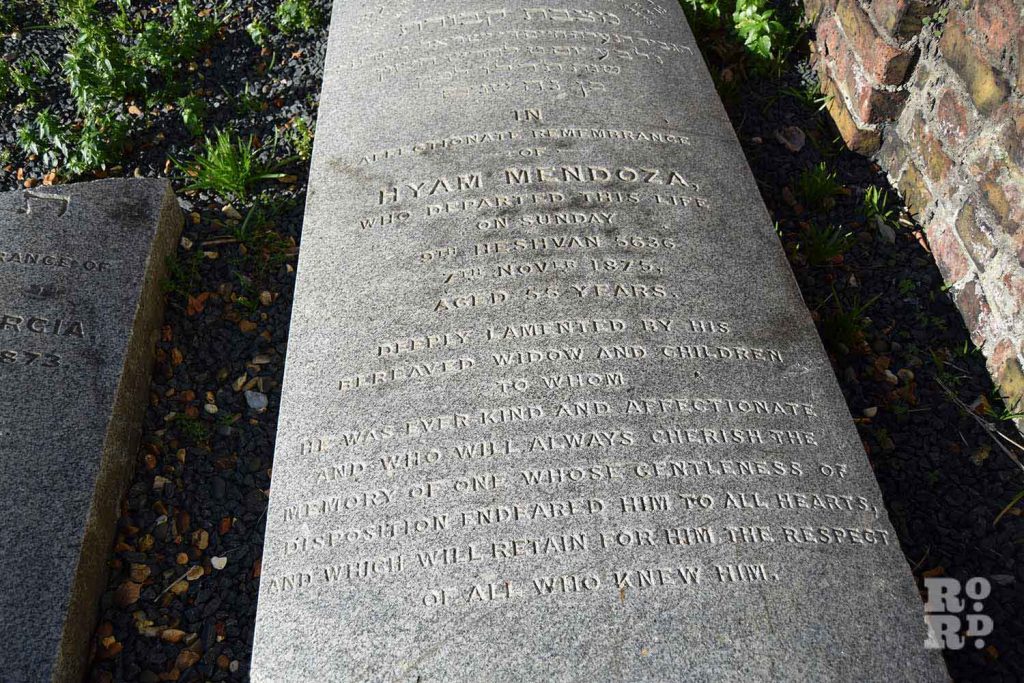

The influence of the British host culture is modest, but apparent. While many of the graves at the older Velho Cemetery are inscribed in Portuguese, most epitaphs at the Novo Cemetery are written in both Hebrew and English, with English calendar dates translating and occasionally replacing the Hebrew calendar dates.

Along with the embellished gravestones, members of the community increasingly adopted sentimental epitaphs, disregarding the long-standing Sephardic tradition of keeping them strictly factual. Many epitaphs immortalise the departed, preserving parts of their identity in stone; Benjamin Wooley Hart (1813-1893) was “a respected member of the congregation”; Eugenie Compertz Montefiore (1862-1893) was “a perfect wife, mother and friend” who “sang herself to sleep.”

Epitaphs consisting of lengthy, emotional verse are also common. The gravestone of 19-year-old Edith Hannah de Pass, who died in childbirth in 1893 and reunited with her infant seven months later, is inscribed with the final lines of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem ‘Footsteps of Angels’: “Oh, though oft depressed and lonely, all my fears are laid aside/ If I but remember only, such as these have lived and died.” Some epitaphs are short statements of loss, grief, and love. The gravestone of a husband buried next to his wife 22 years after she passed away, reads: “Together once more.”

The Novo Cemetery grew with its community, nurtured by a steady stream of immigrants, and by 1918 every patch had been filled. By that point, the community had sprouted from a small group of wealthy merchants to a full-blown microcosm of society at large.

The cemetery reflects this rich diversity, hosting some of the richest Jewish families of their time, such as the Montefiores, Sassoons, da Costas and Disraelis, together with the working-class Jews who would make up half of the annual burials, as well as foreign Jews from countries like Jamaica, Morocco and Australia, South Africa, and Gibraltar.

Undistinguishable, rich merchants from the West Indies lie next to poor cigar makers from Whitechapel; factory owners a foot away from their workers. The grave of a poor ostrich feather sorter, Hannah Genese, who passed away “after a long and painful illness” at age 31, is only a few rows away from the heiress of a wealthy ostrich feather manufacturer, Lizzie Finzi, who died even younger at age 26.

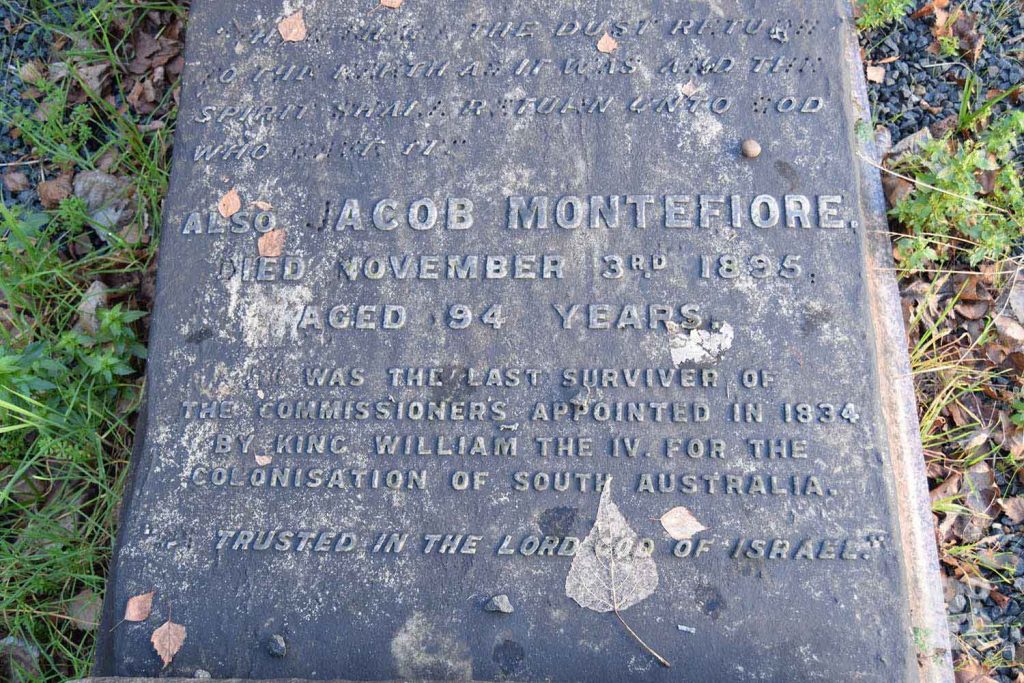

Some of the people buried at the Novo Cemetery are notable figures in global history. Henry Napthali Hart (1818-1891) was a merchant and a key figure in establishing the first synagogue in Argentina, and Jacob Montefiore (1819-1885) was one of the first commissioners for the colonisation of South Australia.

Others influenced the U.K through significant contributions to science as well as society. Jacob de Castro Sarmento (1691-1762) was one of the first Jews to graduate from a British university and a pioneer of the smallpox vaccine in England. Solomon da Costa Athias (c. 1690-1769), was a writer and merchant who donated the foundation of the British Museum’s collection of Hebraic literature and material.

Perhaps the most famous is the boxer Daniel Mendoza (1764-1836), whose scientific technique revolutionised the sport, combated Anti-Semitic stereotypes and made him the most accomplished boxer of his time.

But if you’re looking for Jacob de Castro Sarmento, Solomon da Costa Athias, or Daniel Mendoza, you’re too late. In 1974, 56 years after it was officially closed, Queen Mary University acquired the cemetery in order to expand the campus. A library, student accommodation, lecture halls and student cafes now covers the former burial ground.

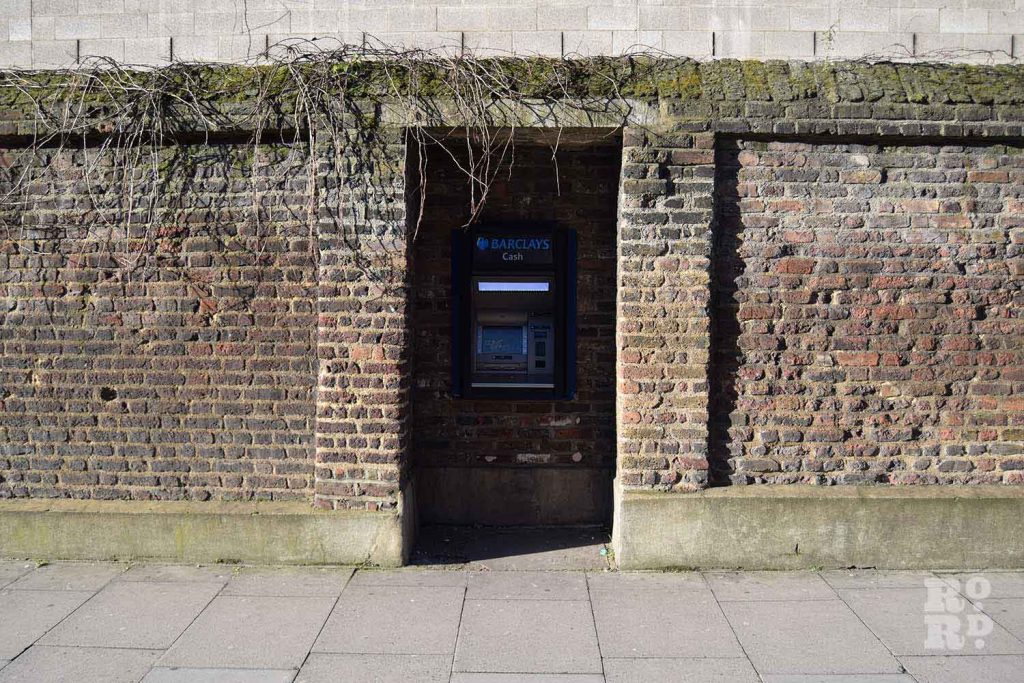

In consideration of their living relatives, the patch holding the deceased of the past 100 years was kept intact and those buried between 1733 and 1875 were exhumed and reinterred in a mass grave in Brentwood, Essex, further entangling the rich and the poor, the famed and the unknown. Parts of the old brick wall still outlines the former width of the cemetery, a Barclays cash machine jammed into the side facing Mile End Road.

On our way out, we pick up scattered Red Bull cans, a soy sauce pouch, a Starbucks cup crinkled into the space between the graves of mother and daughter. Visiting the Novo Cemetery, it’s hard not to reflect on the ethical issues that arise when city expansion clashes with heritage sites of historically dispossessed groups.

We leave small piles of pebbles untouched. They have been left on top of gravestones by visitors as a humble declaration of remembrance. Much like the dead, the Novo Cemetery is gone, but not forgotten.

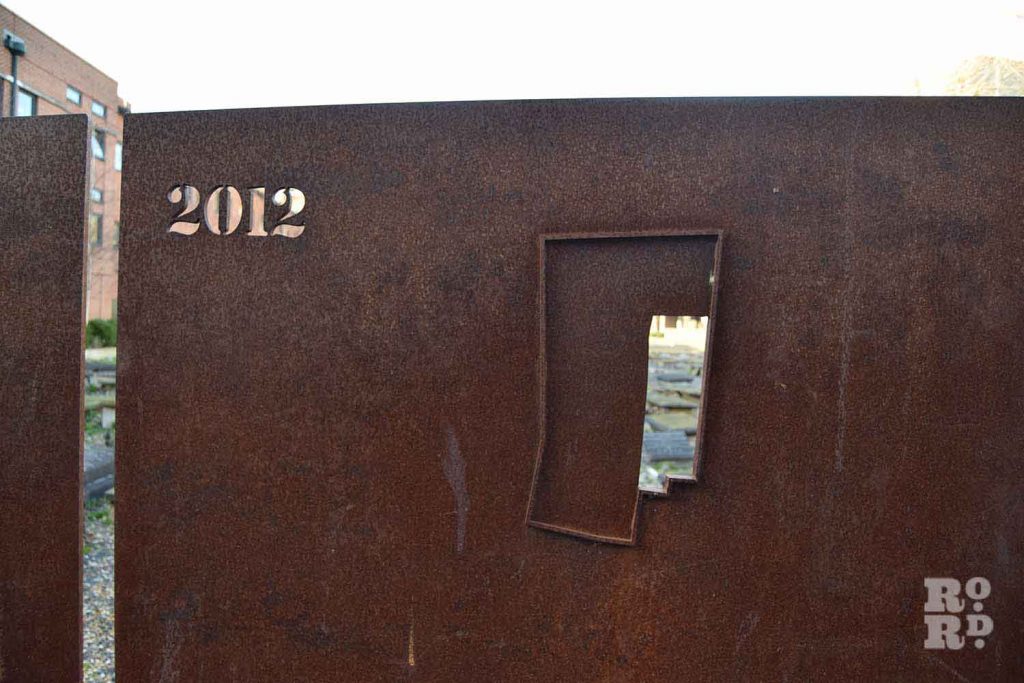

The cemetery is found on the Queen Mary University campus, which is accessible to the general public. Research for this article draws on Dr Caron Lipman’s book “The Sephardic Jewish Cemeteries at Queen Mary, University of London”, 2012, London: Queen Mary University of London.

What an excellent article is it possible to visit this site ? Thankyou for your research we have such an amazing cultural heritage to admire on our doorstep.

Thank you for this article, Queen Mary University shamefully neglects this site as it shamefully neglects the local population.

Zilpha Lake it is just a cemetery thats why they dont care. They are dead now and there is no need to feel bad for it

Massive credit for the shout out to the jewish members of our community and their history in Bow and their contribution to our city. I love that London has these secret and special corners so thank you for sharing them with us.