Celebrating Sarah Chapman and the other unsung heroes of the Match Girls Strike

Citizen journalist Nicola Rushton talks to Sam Johnson, a descendant of one of the women who led the Match Girls riots, about her campaign to acknowledge the contributions of the lesser-known working women who took part in the 1888 strike at the Bryant and May factory.

Sam Johnson, 53, went to find the grave of her great-grandmother Sarah Chapman after discovering she was one of the Matchgirls. She was shocked to find that Sarah had been buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave and planned to erect a headstone – only to learn the site is under threat.

Inspired by her great-grandmother’s revolutionary spirit, Johnson has set up The Matchgirls Memorial charity to save Sarah Chapman’s grave and raise funds for a permanent memorial to recognise the achievements of the Matchgirls. Their victory is not only remembered as a feminist working-class movement but it was also one of the first organised labour movements.

‘I knew my Great-Grandmother’s name was Sarah Chapman and on a census it said she was a matchmaking machinist – but it didn’t say where and I didn’t think anything of it.’

Typing her great-grandparents’ name into a search engine, the top post was from a genealogy forum in 2003 from Anna Robinson, now a poet and lecturer at East London University. Anna had been looking for information on Sarah as one of the leaders of the 1888 Matchgirls Strike against the Bryant and May factory in Bow.

Johnson couldn’t believe it, ‘Suddenly we had all of this information but if Anna hadn’t posted that plea for information thirteen years before, we never would have known.’

Buried in Manor Park Cemetery, Johnson had successfully gained permission to erect a headstone, with donations from Unite London and Eastern Region and GMB National. Now the grave has been threatened by mounding – a process where the existing gravestones are removed, the ground levelled and new earth put on top.

Once the earth has settled, new burials are made. The cemetery, which is a private business, has refused to answer basic questions about the mounding process, leaving the family with concerns about the impact on existing remains.

Johnson believes the discovery of her ancestor’s story has been timely, with resonance between the events of 1888 and inequities in society today.

‘I feel passionate about sharing the story so that the new younger generation can learn from it – particularly in the East End because it’s their story.’ Partly her charity aims to bring the Matchgirls back to the front of the national curriculum.

‘They had very low pay, terrible conditions, 12-14 hour days, 6 days a week. Some people couldn’t afford shoes and then they would be fined if they had dirty feet,’ Johnson explains.

‘They started out with low wages and then after the fines they would receive, they could end the week with hardly any money.

Then they had Phossy jaw to contend with. Workers had been made to eat their lunch inside the factory where toxic white phosphorus was in the air, contaminating their food and resulting in deterioration of the jawbone and in worst cases, brain damage.

The collective frustration of this tight-knit East End community had reached a tipping point. 1400 workers, predominantly teenage girls, walked out in what was the first successful strike by women, with all of their demands met in only twelve days.

Johnson believes what made this strike so effective was the combination of social reformers on the outside working with the people suffering on the inside.

‘We know that largely the workforce were very young, predominantly women and we understand that probably a lot of them were Irish, so a lot of immigrants who would have been very poor – but obviously very feisty as well. There was change in the air.’

The influential socialist think tank, The Fabian Society, held a meeting discussing the state of female labour, prompting journalist and social reformer Annie Besant to interview workers outside the factory and publish their experiences in the newspaper, The Link.

Bryant and May threatened Besant with libel, the workers were fired and they were all ordered to sign a document to say the article was untrue.

In response, the girls stuck together and fought back, in what Sam describes as ‘the power of women, undoubtedly.’

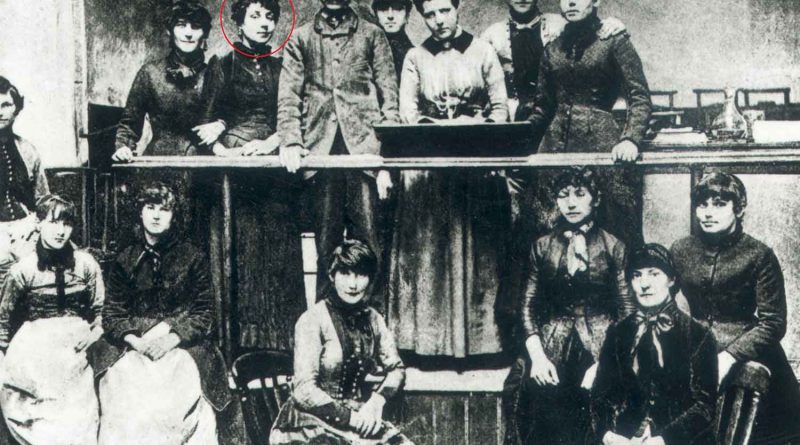

From Mile End they marched to Besant’s office, where three women including Sarah were invited in and together they formed the strike committee. Besant used her contacts to spread the word, resulting in more bad publicity for Bryant and May. She took the girls to the House of Commons where they gained support first from MPs, followed by the London Trade Council and Toynbee Hall.

‘They had a couple of failed strike attempts before so they always had the will to do it, but they didn’t have anyone to back them up,’ Johnson says.

‘So what was different about 1888 was they had people on the outside who were willing to help them.’

Saving Sarah Chapman’s grave and building a statue would ensure that the contributions of the working-class girls are recognised, along with the work of wealthier, more powerful women like Annie Besant.

‘More and more, we are finding these amazing women in history who have just been brushed under the carpet’, she says.

‘The Matchgirls are so significant because you can’t ignore the girls in it; although lots of historians have called it the Annie Bessant Strike and she has often been the only one named.

‘Which is not to take away from the help she gave them but it’s almost as if in lieu of a man to give the credit to, they gave it to the next best thing which was a well-known middle-class woman.’

The Matchgirls Memorial charity is looking at various ways to memorialise the strike, from street names to murals or most meaningfully, statues of the girls.

As Johnson explains, ‘There are a woeful lack of statues that are real women. Stats from 2018 say real women (not nymphs and angels etc) make up 3% of statues in Britain. So to have a statue for an entire collective of women who have actually made a change would be fantastic.’

Johnson is keen to engage with the community and says that, ‘in an ideal world we would love to have a young local East End female sculptor to do the work just because it would be so representative of that event.’

Currently she is running a petition that at the time of writing has gained over 6600 signatures to save Sarah Chapman’s grave and will be working on plans for memorials and awareness with her chairty’s patrons, Anita Dobson, Diana Holland and Barbara Plant.

So what does Johnson think is still so relevant about the Matchgirls for people today?

‘There are so many different workforces today that are coping with terrible conditions – zero hours contracts, people being paid meagre wages for long hours. You would think today that sort of treatment would have ceased to exist but it’s still a struggle.

‘Take heart from what happened 132 years ago and think that you can make a change if you stand up for your rights and say: we deserve better than this.’

If you would like to support Sam Johnson’s campaign, visit the Matchgirls Memorial campaign website.