How an article by activist Annie Besant led to the Bryant and May infamous Match Girls Riots

Born in 1847 and rising to fame as a political activist in the mid-late 1800s, Annie Besant was a key figure in the area’s famous Match Girl Riots. You may know Bow Quarter as the smart gated community on Fairfield Road, but this historical residential complex – all exposed brick, mezzanine levels and light-filled living spaces – was once London’s largest factory and home to a landmark event of the early days of socialism.

The figure-head behind it all was Annie Besant, a socialist and women’s rights activist. A Londoner by birth, Besant married at age 20. Her husband, Frank Besant, was a member of the clergy, somewhat of a sticking point for Annie as she became increasingly interested in secularism and opposed to the idea of the state and its laws being so intrinsically linked to the church and religion.

It was not to be. Just six years after tying the knot, Besant separated from her husband. Divorce was not an option at the time but thanks to her standing in society, she was able to live separately from him and still continue to see her children. It was in this period that she became a leading speaker for the National Secular Society and formed a friendship with writer Charles Bradlaugh, who held many of her views.

Annie Besant activism

She lived with Bradlaugh and his children for some time, as he was standing to become an MP for Northampton. It was in this period that Besant gained notoriety in society and with the public. She and Bradlaugh agreed to publish a controversial book by Charles Knowlton, an American birth control campaigner who insisted that working-class and lower-income families could only rise up the social ranks if they were able to decide and control how many children they would have.

The publication of the book made both Besant and Bradlaugh famous. It was an absolute scandal, seen as salacious and irresponsible. The church opposed the book, of course. The election of Bradlaugh as MP for Northampton in 1880 indicated the support and popularity they had gained with the ‘common’ people of Britain due to their socialist leanings.

The book was a catalyst for Besant’s life as an activist from the 1880s onwards. She studied at the Birkbeck Literary and Scientific Institute, where her political and anti-religion activities intensified. The institution took offence and became unsettled by her free speech and open opposition of the church and secularism, instead of welcoming her. The university’s governors even tried to withhold the publication of her exam results at some point, so as to restrict her political sway.

This didn’t stop Besant though, who by now, was also writing regular columns for The National Reformer, a publication that aimed to dispel secularist myths and spread the notion that Britain would function better as a society if free of the shackles of the Church of England. As well as writing this column, she started to speak at public lectures on the same topic, travelling the country as a sought-after orator on social rights, women’s rights and secularism.

Annie Besant and the Bryant and May Match Girl Riots

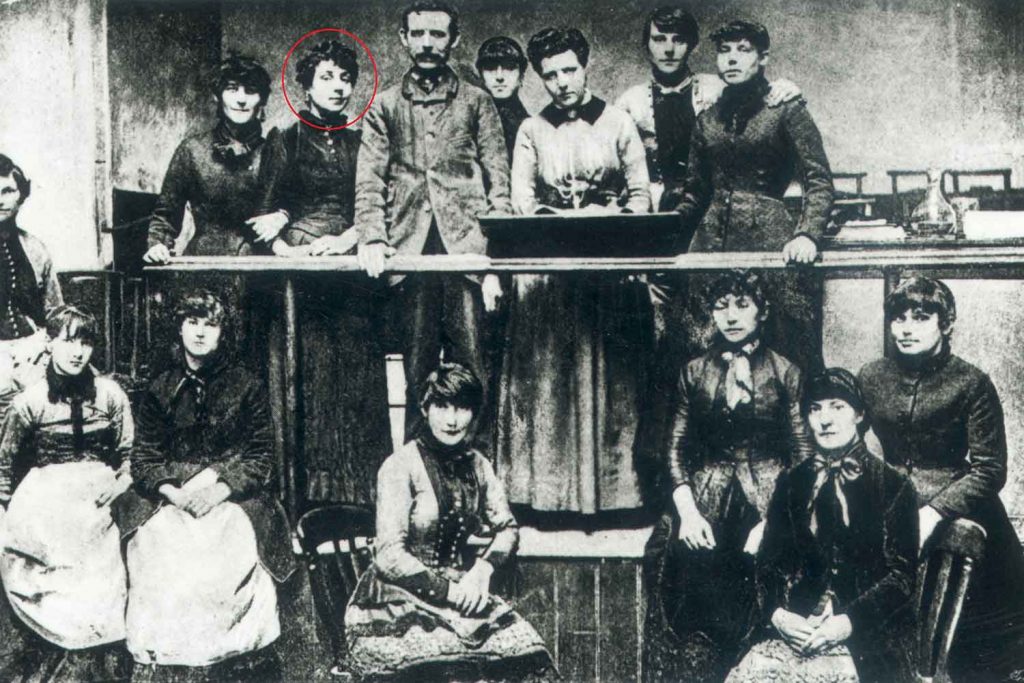

It was Besant’s interest in workers rights and women’s rights that led her to write a now infamous article published in The Link, her own socialist paper, on 23 June 1888. The article was an attack on the Bryant and May match factory (now Bow Quarter) and its poor treatment of the workers there, many of which were young women and girls working fourteen-hour days on paltry wages.

The article accused the factory and its owners of terrible working conditions. Constant exposure to phosphorus was resulting in many developing phossy jaw, a health complication in which the skin of the jaw slowly rots away (and you thought your job was bad.) To add to the terrible hours and pay, workers were often required to pay excessive fines and had their wages docked unfairly by the company.

Some years earlier, the factory owners had faced public scrutiny for their decision to deduct wages from their workers, including many children, in order to fund and erect a statue of William Gladstone in Bow Church. Once the statue was unveiled, the workers and their families expressed their outrage by repeatedly smearing Gladstone’s hands with blood-red paint.

The statue still stands today, hands still scarlet, in spite of the number of times authorities have tried to shine, polish and scrub them clean.

Besant’s article led Bryant and May to demand all workers sign a paper that opposed the claims. The workers refused, which led to an unfair dismissal of one match girl, which in turn led to the entire workforce (1400 women) striking for the entire day of 5 July 1888. Work ground to a halt for a full 12 days due to the strike, which for the largest factory in London, meant huge losses.

Besant met the workers at the factory and set up a committee to make the strike more official. Thanks to her visible support of the women, the public also got behind the strike and the ‘Match Girl Riots’. with demonstrations that promenaded the streets of the East End. Bryant and May gave in within a week and promised to improve pay and the working conditions at the factory. Three years later in 1891, another match factory opened in Bow. Owned by the Salvation Army, this factory committed itself to using less toxic materials and to paying better wages.

Tenacious in her belief in the match girls’ cause, Besant helped the women set up a union and a social centre. The strike and the match girls’ subsequent win was no easy feat at the time. Electric light was still widely unavailable and match sticks were a commodity. The matchstick industry wielded immense power, surpassing even the government and successfully resisting any proposed tax increases. The match girls’ campaign marked the first instance of challenging and defeating the match manufacturers, resulting in a significant victory not only for the workers but also for British socialism as a whole.

Annie Besant’s Legacy

Following all this, Besant continued as a writer, orator, socialist and women’s rights activist. She was the only woman to be elected to the London School Board for Tower Hamlets at a time when women didn’t even have the right to vote. Besant then moved to India to develop her interest in Theosophy, where she helped establish the Central Hindu College and campaigned for democracy in India.

She died at the ripe old age of 86 in Madras, where she continued campaigning for the rights of common people until her very last day.

The East End Women’s Museum is also profiling many of the important female activists of Bow, should you want to find out more about the heritage of worker’s right and suffrage in the east end.

If you liked this, you may also enjoy reading about Sylvia Pankhurst and the Toy Factory.