Migrants and the working class: How the populous has shaped the political history of Tower Hamlets

Often seen as a rambunctious and at times vociferous borough, Tower Hamlets should be proud of its role in shaping democracy as we know it today

Some say Tower Hamlets doesn’t have a good image. MP Paul Scully certainly did when he described it as a ‘no-go’ area in February 2024. Tower Hamlets may be known for its vocal, sometimes riotous, populous but from our irrepressible East End, we’ve witnessed political movements that have shaped our modern-day democracy.

In 1720 John Strype’s Survey of London split the city into four parts: the City of London, Westminster, Southwark, and ‘That Part beyond the Tower.’ This was the first known time the East End was referred to in writing as a distinct area.

Since then, the area has cohered into one of the UK’s most colourful sites of political change, known for its progressive movements and influential social reformers, who have been willing to lay down their lives for their causes, whether through battles, hunger strikes, or imprisonment.

The strikes that founded Workers’ Unions

In the late 19th century, Tower Hamlets was a site of dense industry. Due to being downwind from the rest of the city, the area was populated with smokey factories and strong-smelling industries like tanning. There was also the increasingly busy Eastern Dock, near which many Irish migrants worked and lived. In Whitechapel, the clothing industry was largely staffed by Jewish migrants.

Politically, in these times the East End constituencies were mostly Conservative, except Whitechapel which tended Liberal. Whitechapel also hosted an intriguing underground movement of Jewish anarchists.

Although the factories, industries and docks of the East End were extremely profitable, the people who manned them were making very little money, while working and living in cramped and unsafe conditions. One such case was the Bryant and May factory Match Girls strike in 1888, where the factory’s largely female staff went on strike to improve their working conditions and pay.

The factory was forced to recognise the resulting Union of Women Match Makers and was later exposed for covering up the harm caused to the workers by their exposure to toxic phosphorus. The strike preempted the emerging New Unionism movement, which hugely increased the bargaining power of ‘unskilled’ workers.

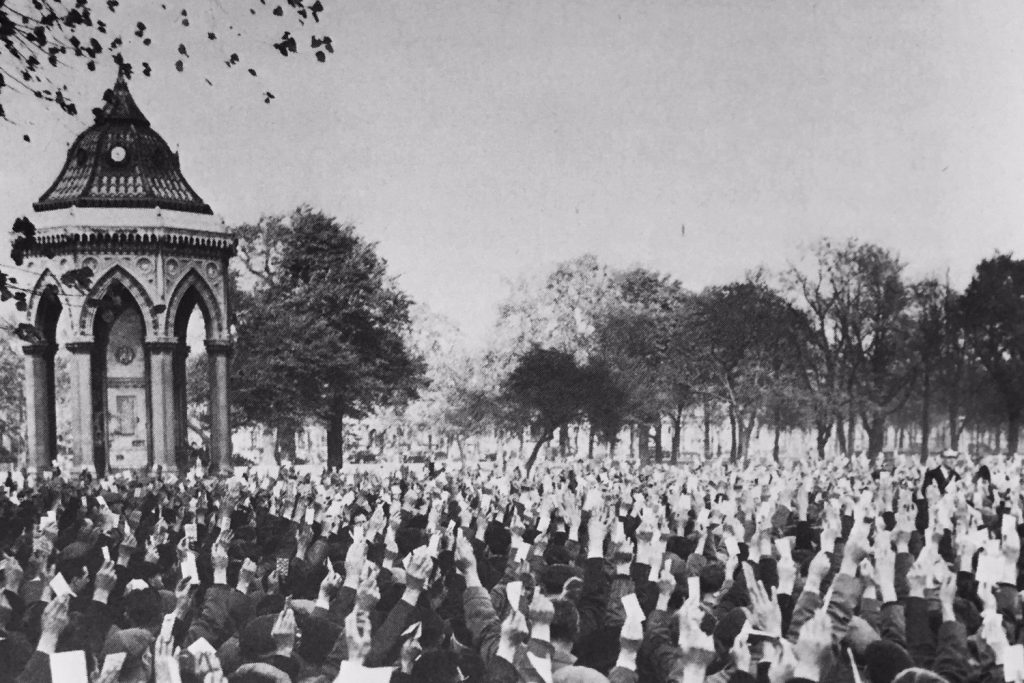

In 1889, dockers in the East End went on strike. More than 100,000 dockers brought the world’s largest trading port to a halt, over low pay and bad working conditions. Dockers at the time were forced to line up at intervals throughout the day for the possibility of work, which was badly paid and never guaranteed.

The largely Irish workforce was concentrated in Poplar. Union leaders met in Poplar’s Wade’s Arms pub and were kept nourished by its sympathetic landlady.

Two weeks into the dockers’ strike, 10,000 of Whitechapel’s mostly Jewish tailor community also went on strike. They were also seeking improved pay and working conditions.

Tailors were used to cramped working conditions and long, exhausting days, at the end of which they were often made to bring home unfinished work. The organisers would meet at the White Hart Pub in Greenfield St.

Both groups of striking workers were supported by their local communities and ended up sharing resources bringing previously insular communities closer together.

The mass strikes of 1889 paved the way for stronger, more politically involved unions in the UK. Over the next ten years, trade union membership grew from 750,000 to over 2 million. This newfound strength of the unions led to the rise of a new party, the Labour Party, in 1900.

Middle-class Liberalism and Philanthropists

In the late 1800s, the East End suffered from extreme poverty, dangerous working conditions, overcrowding, and poor sanitation services. These conditions bred high rates of crime, addiction and mortality.

The Victorian middle classes profited largely from cheap labour supplied by places like the East End. Simultaneously, poverty was seen as a social disease which could be cured with good morals, and/or with the help of the more fortunate.

During this period wealthy benefactors like Dr. Barnardo, Baroness Angela Burdett-Couts, and Samuel Barnett led progress in the East End by funding projects for housing, schooling, green space and education.

Despite huge social benefits, philanthropic social reform at the time was undemocratic and completely up to the whims of the philanthropist. For example, Dr. Barnardo, whose focus was child poverty, was accused of kidnapping the children he was protecting.

Yet these early charitable ventures put down roots for more comprehensive public services later on. The ‘Ragged Schools’ which provided a free education to very poor children laid the foundations of what later became free state schooling.

The Suffragetttes and the fight for women’s votes

Throughout the late 1800s, the movement for women’s votes was slowly gaining traction. In 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) to gain female emancipation.

In 1912, Sylvia Pankhurst broke away from the original WSPU and set up her own branch in Tower Hamlets, Bow. Sylvia’s politics were more radical than that of her family and many other Sufraggettes of the time. She sought the support and mobilisation of working-class women.

Pankhurst was familiar with Bow due to previously campaigning there for Labour MP George Lansbury. The same year she set up her branch of the WSPU in Bow, Lansbury resigned from his Labour seat in the constituency. This was because Labour was unsupportive of the women’s vote.

The fight for women’s votes in Bow produced several revolutionary figures aside from Pankhurst, including Minnie Lansbury, Julie Scurr, and Nellie Cressall.

The group led marches and protest actions for suffrage, but they also set up cooperative factories and food banks for working-class women during the war. By 1918, some women in the UK (householders over 30 with university qualifications) had gained the right to vote. It took another ten years for full voting rights.

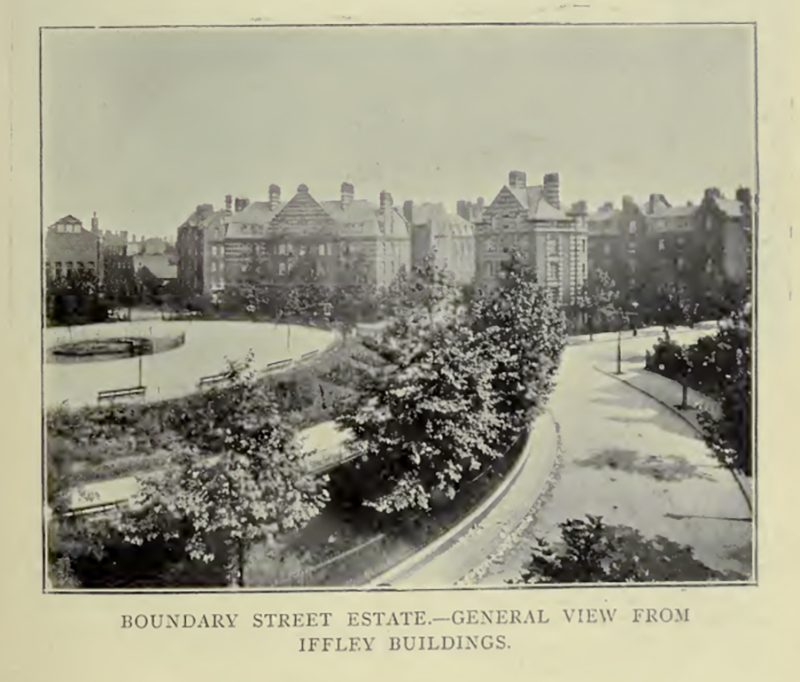

Housing reform and the birth of Council estates

In 1900 Britain’s first council estate opened, the Boundary Estate, in Tower Hamlets. It was a project of the London County Council, then newly created, and housed 5,100. The Boundary Estate was controversial because only eleven residents of the demolished slums it replaced were housed in the new estate. Nonetheless, it marked the start of a long history of social housing in the UK.

The next chapter of housing reform continued in Tower Hamlets with the political figure George Lansbury. Prior to becoming the leader of the Labour Party, Lansbury was twice elected the mayor of Bromley and Bow.

In 1921 Lansbury attempted to reduce the amount poor residents had to pay to the London authorities, known now as the Poplar Rates Rebellion. Residents were charged higher rates than wealthier neighbourhoods because their lower rents made the authorities less money.

Lansbury refused to collect the higher rates from residents of Bromley and Bow as a form of tax protest. The action led to his arrest and imprisonment for six weeks, but it made him a local hero and helped define Labour’s reputation as a party for the working class.

The term ‘Poplarism,’ was coined as a result, referring the the revolt of local government against the national. In 1931, Lansbury became the Labour Party’s leader and remains one of its most respected figures today.

By the late 1930s, housing costs were a mounting issue in Tower Hamlets and the Second World War was around the corner. The government’s 1915 Rent Control Act had faded into disuse, leaving landlords free to steadily up rents. Bethnal Green’s Quinn Square was no exception. Its landlords had been raising rents for years while neglecting repairs.

In 1938, Quinn Square’s tenants, led by women, organised a rent strike. The women picketed the agents daily, demanding rent control, recognition of their Tenant’s Association, and the carrying out of repairs.

Not one tenant from the 247 flats paid their rent until the landlords accepted the demands two weeks later. With the Conservative government refusing to moderate rents, Quinn Square’s tenants took matters into their own hands. Inspired by their success, rent strikes spread across the East End.

From setting the precedent for council housing to ‘Poplarism,’ rent control and rental unions, Tower Hamlets saw some of the earliest and most effective forms of housing reform.

The fight against fascism

In the 1930s, Tower Hamlets’ high Jewish population was a political hotspot with the rise of anti-semitism in Europe. In 1936, Oswald Mosely of the British Union of Fascism (BUF) planned a march with his ‘blackshirt’ party members through the East End.

The BUF was closely aligned with Hitler’s principles and chose to march through the East End to terrorise the Jewish community. Instead, it’s said that hundreds of thousands of people showed up to stop the march from going through.

Led by Phil Piration, the leader of the Communist Party of Great Britain, locals barricaded the streets to stop the march, including Cable Street. They bitterly fought the police who tried to allow the blackshirts to pass, and the day was known as ‘The Battle of Cable Street’. The event informed future protest law in the UK, making it so protestors had to notify the police before marching, and banning political uniforms in public.

After the Second World War, the UK government encouraged workers from Commonwealth countries to immigrate to the UK to help rebuild the country. The concentration of manufacturing industries around the docks made the East End one of the areas most heavily impacted by the Blitz and required many new workers to rebuild. This prompted Bangladeshi migration from what was then Pakistan.

By the 70s, the Bangladeshi Declaration of Independence meant a new wave of refugees came to join an established community in Tower Hamlets, largely in Whitechapel. With the Jewish community moving up North, the demographics and politics of Tower Hamlets shifted completely again.

In 1978, Bangladeshi Altab Ali was stabbed in a racially motivated attack on his way home from work in Brick Lane. At the time harassment and abuse of Bangladeshis was common in the area. Racial tensions were high in the borough, and the National Front, a far-right racist party, was gaining support across the country.

Altab Ali’s murder spurred a new wave of anti-racist action and organising in the British-Bangladeshi community. Groups like the Bangladeshi Youth movement formed to fight for their voices to be heard politically. The National Front was driven out of their offices near Brick Lane within the year.

In 1982, the first Bengali politicians were elected to Tower Hamlets council. Almost thirty years later, in 2010, Rushanara Ali would be elected as the Labour MP for Bethnal Green and Bow, making her the first person of Bangladeshi origin to be elected to the House of Commons.

The rise of working-class politics

In the pre-war years, the main parties in Tower Hamlets were the Conservatives and the Liberals. Figures like George Lansbury converted the Liberal sentiment to a Labour one, both defining and strengthening working-class politics.

In 1924, the first Labour government was formed. Tower Hamlets (at the time three separate boroughs of Bethnal Green, Poplar and Stepney), remained a Labour majority until the late 80s. With few interruptions in the modern day, the borough is still regarded as a Labour stronghold.

Between 1986 and 1990 Tower Hamlets had a brief and surprising departure from its Labour stronghold. The borough was first a SDP/Liberal Alliance, followed by the resulting freshly formed Liberal Democrats party. At the time, Tower Hamlets’ Labour group was on the right of the new urban Labour. The borough was facing issues like poverty, lack of housing, loss of industry and racial tension, and ready for a change in leadership.

When the Liberals took power, it was with the motto ‘Power to the Hamlets.’ While in power, the Liberals trialled a radical form of decentralised local government. The borough was split up into seven neighbourhoods, each run by an independent local committee. The idea was to spread out power hyper-locally.

The decentralisation had mixed results, one issue being the difficulty created for residents trying to move between neighbourhoods. In 1993, the Liberal Democrats distributed racist leaflets implying that Labour-controlled neighbourhoods were disadvantaging white tenants. The controversy linked the area’s housing shortage to Black and Asian people.

The Liberal Democrats lost popularity in the borough, and the same year the racially divisive British National Party (BNP) won its first-ever elected official in the Isle of Dogs. The surprising win spoke to rising racial tensions in the borough.

The next surprising loss of a Labour seat came in 2006, when George Galloway became the MP for Bethnal Green and Bow. In large part, his campaign was in protest of the Iraq war. It emerged later that the Islamic Forum of Europe had supported Galloway in his campaign.

In 2010, the Tower Hamlets council, which at that point had been a unified borough since 1965, changed its power structure. Whereas previously the borough was led by a cabinet and leader, a referendum was passed to replace these with an executive Mayor.

Lutfur Rahman was the leader of Tower Hamlets Council from 2008 to 2010 for the Labour Party, and was initially selected as that party’s candidate for the 2010 Mayoral Election. After allegations of links to a fundamentalist group and of signing up ineligible voters for the selection process, he was removed as Labour’s candidate and left the party to contest and win the election as an independent candidate.

He was re-elected at the 2014 Mayoral Election as the candidate for his party Tower Hamlets First, but the result of this election was declared null and void when he was found guilty of electoral fraud, and the following year Labour’s John Biggs took the seat. After a five-year ban, Rahman stood once again for Mayor and was re-elected in 2022 as part of his new party called Aspire, a seat he still holds today.

Rahman has the support of both the Muslim community and also of ‘left-of-Labour’ supporters disillusioned with what is seen as the Labour Party’s ‘rightward’ path under Keir Starmer. Many supporters of Jeremy Corbyn praise Rahman’s unabashed socialist policies.

What’s next?

Our borough’s intense struggles have birthed some of the UK’s most important political movements. From the first social housing, votes for women and Poplarism, to the rise of the Workers’ Union, and rent reform, the journey isn’t over.

Today, Tower Hamlets continues to be at the coalface of some of modern society’s biggest challenges. Our borough struggles with high child poverty rates, a cost of living crises, homelessness, low air quality and overcrowding, to name a few.

But as we’ve seen over the years, these challenges test our democracy and force us to find solutions. Often, our solutions become the blueprint for nationwide change. Much of the development of democracy has happened in areas of hardship, and Tower Hamlets is no exception – it might even be the rule.

If you liked this, you may enjoy the ‘Never Mind their Fingers’: A history of strikes in the East End.