‘Never mind their fingers’: the strikers who bled for the East End

The East End has a vital history of industrial action. From the Match Girls Strike of 1888 and ‘The Great Unrest’ between 1911-1914, to the rent strikes of the late 1930s, East Enders throughout history have bled for the greater good.

If you amble past Bow Quarter on a morning stroll just a stone’s throw from the Roman you may notice a blue plaque indicating where The Bryant and May Factory once stood in 1888. The charming gated community bears no resemblance inside or out to the prison-like conditions endured by 13-year-old girls exploited for a steady profit in the Victorian era.

London Docklands is now similarly a site of urban renewal, with lavish apartments overlooking a quayside abundant with well-off young professionals. The West India Quay is quiet, as it often is, but not as eerily so as in the summer of 1889 when strikes brought the port to a standstill. But these binary silences signify entirely different moments in time.

You could be forgiven for passing by Langdale Street in Shadwell without a moment’s thought. The street sign is accompanied not by a historic plaque, but a barely attended notice board. But sometimes our remarkable history is hidden, because in 1939 an unlikely alliance between Jewish garment workers and dockers, facilitated by a German anarchist, sprung up to combat draconian landlords of the Langdale Mansions.

The years 2022 and 2023 have seen a relentless wave of strikes. The 1 February 2023 was the biggest day of industrial action in more than a decade. Teachers, university staff and civil servants were among tens of thousands who walked out for better pay and conditions. So what moments in our past compelled East Enders to stand up and be counted?

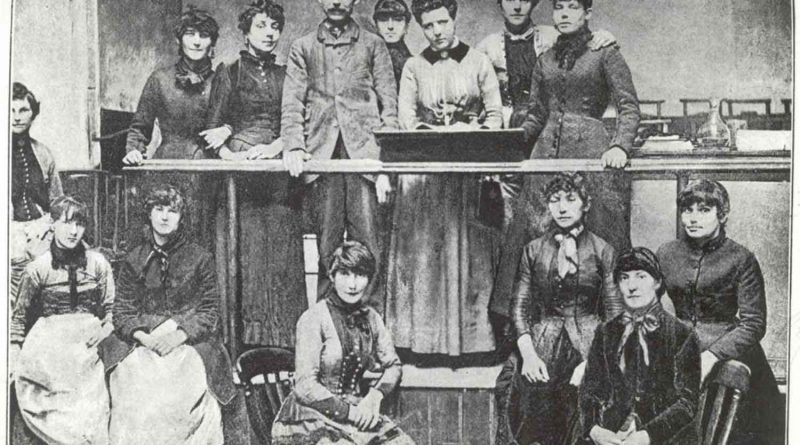

The Match Girls Strike of 1888, where young girls and women protested conditions at Bryant and May Factory, demonstrated the crucial role of East End women in industrial action. Scores were disfigured by cancerous ‘phossy jaw’ after exposure to white phosphorous, routinely had their pay arbitrarily docked and worked 14-hour days. ‘Never mind your fingers’ was as far as safety advice went, so East End women took matters into their own hands.

Activists Annie Besant and Herbert Burrows rallied a walkout of 1,500 workers and forced management to abolish fining practices. Yet, the cancer-causing substance remained in use until banned by the White Phosphorus Matches Prohibition Act in 1908. Twenty years after the strike, progress had been too slow but the heroic deeds of the match girls set a crucial precedent for effective, organised action rooted in the East End. This was the first time an unskilled workers union successfully walked out for better pay and working conditions in London.

The city-wide Great Dock Strike that followed in 1889 was inspired by the match girls’ success. Picture a docker and you think of a burly, self-dependent man. But the actions of the East End’s young girls showed longshoremen the power of industrial action. Class unity was another decisive factor in the 100,000-strong strike that established the Dock, Wharf, Riverside and General Labourers’ Union as a force for change.

Despite the solidarity between dockers and women, a divide between East and West London remained. Gentile tailors in the West and their Jewish counterparts in the East End did not see eye to eye until 1912 when forced together during ‘The Great Unrest’. Jewish tailors had been known as scabs for taking the work of their striking West End counterparts, but peace was brokered by the unlikeliest of figures.

Rudolf Rocker, a German anarchist, convinced Whitechapel’s Jewish garment workers to unionise. Rocker spoke before 8,000 people at Mile End Assembly Hall and two days later 13,000 tailors walked out in the largest East End strike since the match girls. Three weeks later, East and West End tailors won shorter hours, improved sanitary conditions and their factories became closed shops. Jewish tailors in Whitechapel later took in starving dockers’ children showing that humanity had triumphed over factionalism.

Though the dockers, many of whom Irish, did not achieve the same gains as Jewish tailors that year, a crucial alliance had been established. Irish-Jewish communities came together once more to combat Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists at The Battle of Cable Street in 1936. Bill Fishman, a historian who once taught at Morpeth School in Bethnal Green, was an eyewitness at the battle.

Fishman said: ‘It was moving to me to see bearded Jews and Irish dockers side by side as comrades. Some stories, it seems, take decades to play out.’

And just two years after the Battle of Cable Street, renters took up the striking mandate. In the summer of 1939 tensions at Langdale Mansions in Whitechapel reached their limit. Frustrated renters demanding repairs, necessary decoration and rent reductions turned the blocks into a de-facto base. Barbed wire and guards were imposed to keep landlords out, but bailiffs got access. The police moved in with brutal force and tenants had to defend themselves with saucepans, rolling pins, sticks and shovels.

In stepped the Stepney Tenants’ Defence League (STDL), which sent thousands of members to stand with tenants at Langdale Mansions. Landlords ceded to reduce rent and make crucial repairs. Despite the victory, repressive legislation came 18 years later with the 1957 Rent Act that removed almost all private rent caps.

Despite such laws scuppering labour movements throughout history, the saucepan-wielding Whitechapel renter epitomised the East End’s spirit of endurance. The willingness to bleed and a refusal to be cowed when confronted by the jackboot. Not only that, but the helping hand of groups such as the STDL from nearby Stepney ensured working people were given the support they deserve.

As you walk around your neighbourhood you will likely notice the array of classes, ethnicities and cultures. In our dense borough, shops are huddled together and often lie atop one another. The patter of myriad languages and dialects down the Roman, from Bengali to Cockney, is what defines our area.

You may ask, how are we able to cohabit so well in the East End? Our valiant striking past, where East Enders from all walks of life stood up for each other, has played a significant role in forming the close community you see today. The East End served as a beacon of strength for industrial action, from Shoreditch to Stepney, from Whitechapel to Bow, and continues to do so.

For more of our heritage pieces, have a look at this piece on the untold history of Hertford Union Canal.

A very good and informative piece of writing.