“Mendoza the Jew”: the boxing pioneer who fought antisemitism one jab at a time

In our ongoing series about the local Jewish heritage, local citizen journalist Siri Christiansen takes a closer look at a former resident of No. 3 Paradise Row; Daniel Mendoza (1764-1836), the father of the science of boxing.

At a time when Jews in England were second-class citizens, a short, ill-tempered Jewish boy from Aldgate brought his rage to the stage to rebut derogatory stereotypes with fast-paced footwork and a mean straight left.

Little known outside the field of boxing history, Daniel Mendoza was one of the biggest sport superstars of the 18th century, credited with writing the first book on boxing theory and the first sports memoirs.

Proudly Jewish during a period of rampant antisemitism, Mendoza was an unlikely champion of a sport that many considered to be inherently British. Nevertheless, his popularity trumped the controversy and elevated the status of his community.

But long before Mendoza was the subject of headlines, tales and songs, he was an angry boy who had a hard time keeping a job.

One of many children of second-generation Spanish and Portuguese immigrants, his parents weren’t financially able to extend his Jewish education past his bar mitzvah. At age 13, he had to go out and earn his bread.

Over the course of his adolescence, Mendoza flickered through a series of short employments, but his aversion to discrimination and habit of resorting to violence made it difficult to work in retail.

He was an apprentice to a glass cutter before giving the employer’s son a severe thrashing as retaliation for his violent threats. He later found work in a tobacco shop and a tea shop, but the steady trickle of antisemitism caused each employment to end in fisticuffs.

By the time Mendoza entered the workforce, a little more than a century had passed since Oliver Cromwell granted the Jewish people permission to reside in England, practise their religion and establish religious institutions.

The Jewish community in London had grown from around 300 people in 1656 to over 10,000. The rapid increase was attributed to the influx of Ashkenazi Jewish people, escaping persecution in Eastern Europe. Enclaves formed in Aldgate, Whitechapel and Mile End, hosting the diversified mix of influential merchants, rich factory owners, poor cigar makers and beigel bakers.

England was more accepting of its Jewish population than other European countries at the time, but it was by no means a haven of tolerance.

The Jews were considered second-class citizens and were not allowed to own land, graduate from university or participate in civil or public affairs.

Any attempts at integration were quickly thwarted, such as the Jewish Naturalisation Act, which passed in 1753 before being repealed six months later after outcry from the Tory party and press.

Although they represented a small fraction of London’s criminal underworld, Jewish crimes were singled out as symptomatic of an inherent “Jewish character” that implicated the community as a whole. Not only stereotyped as weak and defenceless, the Jews were now portrayed as a threat to the native population and their religion, making them targets for verbal and physical abuse in the streets.

Eager to squash this stereotype, Daniel Mendoza was never one to back down from a fight.

During one such an altercation, the crowd outside the shop attracted the bypassing boxer Richard Humphreys. Recognising Mendoza’s knack for fighting, Humphreys was determined to become his mentor and manager. A boxing match down by Mile End Road was quickly arranged for the following week, starring 16-year-old “Mendoza the Jew” with Humphreys as his second.

When the buff, bare-chested Mendoza first entered the ring on a Sabbath in 1780 – and won against his larger opponent – he immediately raised curiosity.

On physical appearance alone, Mendoza seemed easily defeatable. At 160 pounds and five foot seven inches tall, he remains the lightest heavyweight boxer in history.

To get around this shortcoming, Mendoza used his size to his advantage; instead of relying on brute force, he developed a technique in which speed, footwork and stamina outmaneuvered his opponent.

By the late eighteenth century, boxing gathered large crowds from all social classes, but its development as a sport had stalled.

At this point it was bare-knuckled, illegal, and lawless. The few rules that existed were rarely followed. Simply put, a boxing match consisted of two men swapping punches until someone was knocked out.

When Mendoza stepped into the game, this changed.

His stance was side angled with guarded fists and bent knees, enabling him to beat his larger opponents by side-stepping, blocking and ducking away from their punches. In doing so, Mendoza introduced defense to a sport that had previously only involved offence.

Initially mocked for his unmanly, timorous retreats, the critics clammed up as Mendoza’s technique proved successful; between 1780 and 1788, he was the undefeated champion of 28 straight fights (and after 1789, he was undefeated until 1795).

During this time, he declared himself a “professor of pugilism” and cemented his title by establishing a boxing academy.

From his home at 3 Paradise Row, he wrote one of the first handbooks of its kind, The Modern Art of Boxing (1788), laying the foundation for modern boxing theory.

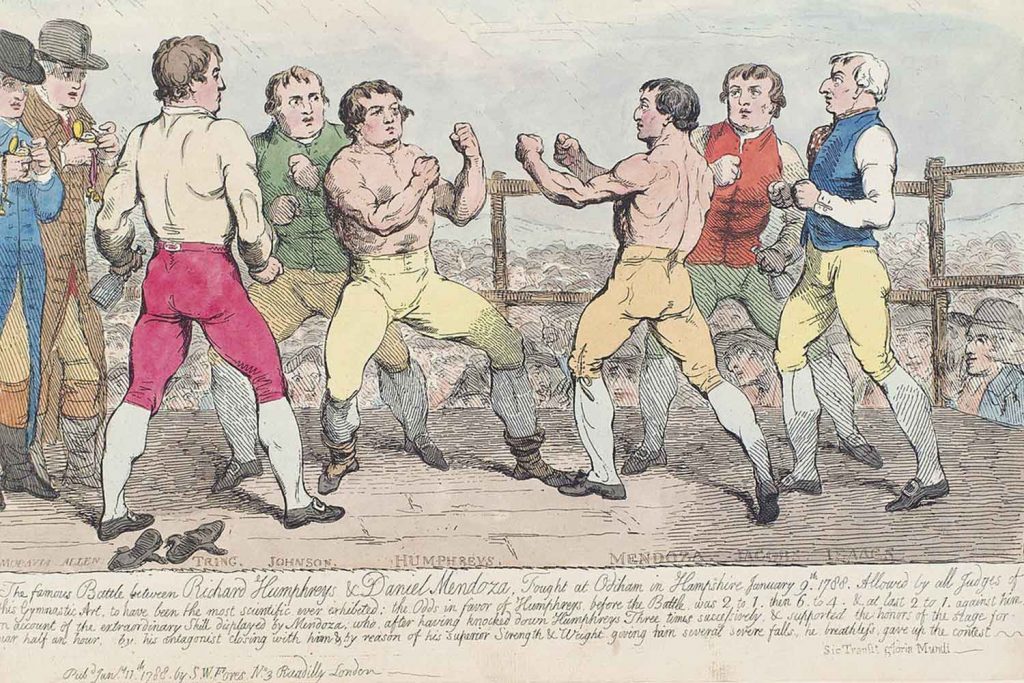

Mendoza’s career reached its height through a trilogy of fights between 1788 and 1790. His rival was Richard Humphries, the same boxer who introduced him to the sport eight years prior.

In the months leading up to each match, the two boxers would hype up interest by staging a public argument in a series of letters published in the newspapers anticipating modern day media stunts

“Mr Humphreys is afraid, he dares not meet me as a boxer”, Mendoza taunted.

“[Mendoza] has insinuated that in his late contest with me at Oldham, his being beaten was the mere effect of accident”, Humphreys would retaliate. “I do now declare that I am ready to meet him, at any time not exceeding three months from the present date”.

Their strategy was effective; it was the talk of the town. Each match attracted tens of thousands of spectators and entered history as the first series of sporting events to charge an entrance fee.

In their final battle, Mendoza was declared the winner as Humphreys collapsed after a whopping seventy-two rounds.

Mendoza rose to superstar status. He received royal patronage by the Prince of Wales (making him the first boxer to do so) and was summoned to a private audience with King George III (making him the first Jew to do so). He was the subject of headlines in England, France and America.

His face was painted on teapots and mugs, engraved on drinking glasses and printed on posters, devoid of the grotesque caricature features otherwise common in depictions of Jews at the time.

Four years later, in 1794, “Mendoza the Jew” defeated Bill Warr and became the sixteenth English and world heavyweight champion. He held the title for one year before losing to John Jackson, marking the beginning of Mendoza’s decline, now 31 years old.

Desperate for money, he spent the remaining years of his life weltering through a hodgepodge of great achievements, odd jobs, and sporadic acts of crime; he toured the country, spent time in debtor’s prison, opened another boxing academy, worked as a recruiter for the army, assaulted a woman, wrote the first sports memoirs and became a landlord of the Admiral Nelson pub in Whitechapel.

Each fortune he made was quickly lost, either to gambling or poor money management. When he died blind at 72 years of age on September 3, 1836, he left his wife and children in poverty.

Although his popularity declined, Daniel Mendoza made a lasting impact on British culture as much as he did in the world of boxing.

In the present day, attempts have been made to revive the local memory of this remarkable figure in Anglo-Jewish history. A blue plaque marks his former residency in Paradise Row. In 2008, after years of campaigning, the Jewish East End Celebration Society installed a bronze plaque at the site of the former Novo Cemetery, now the Queen Mary University Library, in commemoration of the grave that was destroyed during the university’s expansion over the old Jewish cemetery in 1974.

Inside the ring, his innovative techniques raised the sport from primitive punch-throwing to a strategic artform, while outside it, his visibility offered a rare account of positive representation of Jewishness. Empowered by his example, boxing became popular among the Jewish youth.

While violence should never be condoned, Mendoza wouldn’t live to see any other accessible means of demanding respect. Equal rights was a long way down the line; it would take until the 1890s before Jewish emancipation was complete.

Until then, Mendoza taught a generation of working-class Jewish people in east London how to fight back.

If you liked this, you might be interested in reading about Siri Christiansen’s other articles in her series about local Jewish history, including Novo Cemetery and Velho Cemetery.

Hi. Read this with interest. My GG Uncle was Jack Burke The Irish Lad was a Bare Knuckle fighter, holds record for longest fight. Born in Killarny in 1861 came to London fought over Hackney Marshes, traveled to USA, Australia. Went on to own The Florence Tavern in Islington Died in 1896 Has a Monument in West Norwood Cemetery

The unveiling of the Jewish East End Celebration Society plaque in Mendoza’s memory was a terrific event. We were lucky enough to have members of the Mendoza family there, and Henry Cooper made a very good speech about Mendoza and the many other boxers who subsequently emerged from the Jewish East End.