From sixties youth group to East End nirvana – the origins of the London Buddhist Centre

With its origins in north London, the story of how the London Buddhist Centre came to operate from the Old Bethnal Green Fire Station is an extraordinary one. A tale of resourcefulness, resilience and hard graft – with a sprinkle of good fortune – it is emblematic of the transformation of the self in Buddhism (known as the Dharma) and the wider rejuvenation of much of the East End over the past decade-or-so.

Before moving to Globe Town, the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order (FWBO), as they were known back then, were based in Archway, north London. Their main centre was significant only for its proximity Karl Marx’s tomb in Highgate Cemetery – just a stone’s throw away. And at the time of their first convention in 1974 they had barely 20 members to their name.

A Sixties youth movement

This membership mainly comprised twentysomething veterans of the Sixties youth movement. As Subhuti, current President and former Chairman of the London Buddhist Centre recalls, their mantra was ‘sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll… at least in theory.’ But this co-existed with serious attitudes that were prevalent among much of the younger population during that tumultuous time. ‘There were all sorts of vague, anarchic ideas that went with that – getting rid of the old and on with the new! We saw Buddhism as a part of that.’

And it was a case of ‘out with the old and in with the new’ that prompted this rough and ready band to look for new digs. Word came down from the local authority that the area they’d been squatting in was earmarked for demolition, with plans for redevelopment; London was still in the process of rebuilding in the post war era. So, it was time to go.

Finding new premises, however, would be no easy task. The community could barely scrape together a living between them. They were living a hand-to-mouth existence. One member, as the story goes, had given up their acting career and was living off the royalties from a beer advertisement. So, perhaps not the most dynamic or pro-active group.

It was Subhuti that devised a master plan to scour London for their next spiritual base of operations. He took a large map of London, divided it up and assigned members their own patch of the capital to search for vacant properties. They considered a number of old school buildings and a grand Georgian house opposite the British Museum. They even sought assistance from estate agents.

A new home in an old fire station

During all this, though, someone came by a flyer for the Old Bethnal Green Fire Station. It had been vacated in 1968; the fire brigade had moved just a few doors down to a custom built, Bauhaus-inspired concrete castle. So, was the old station going to be their gift from the gods?

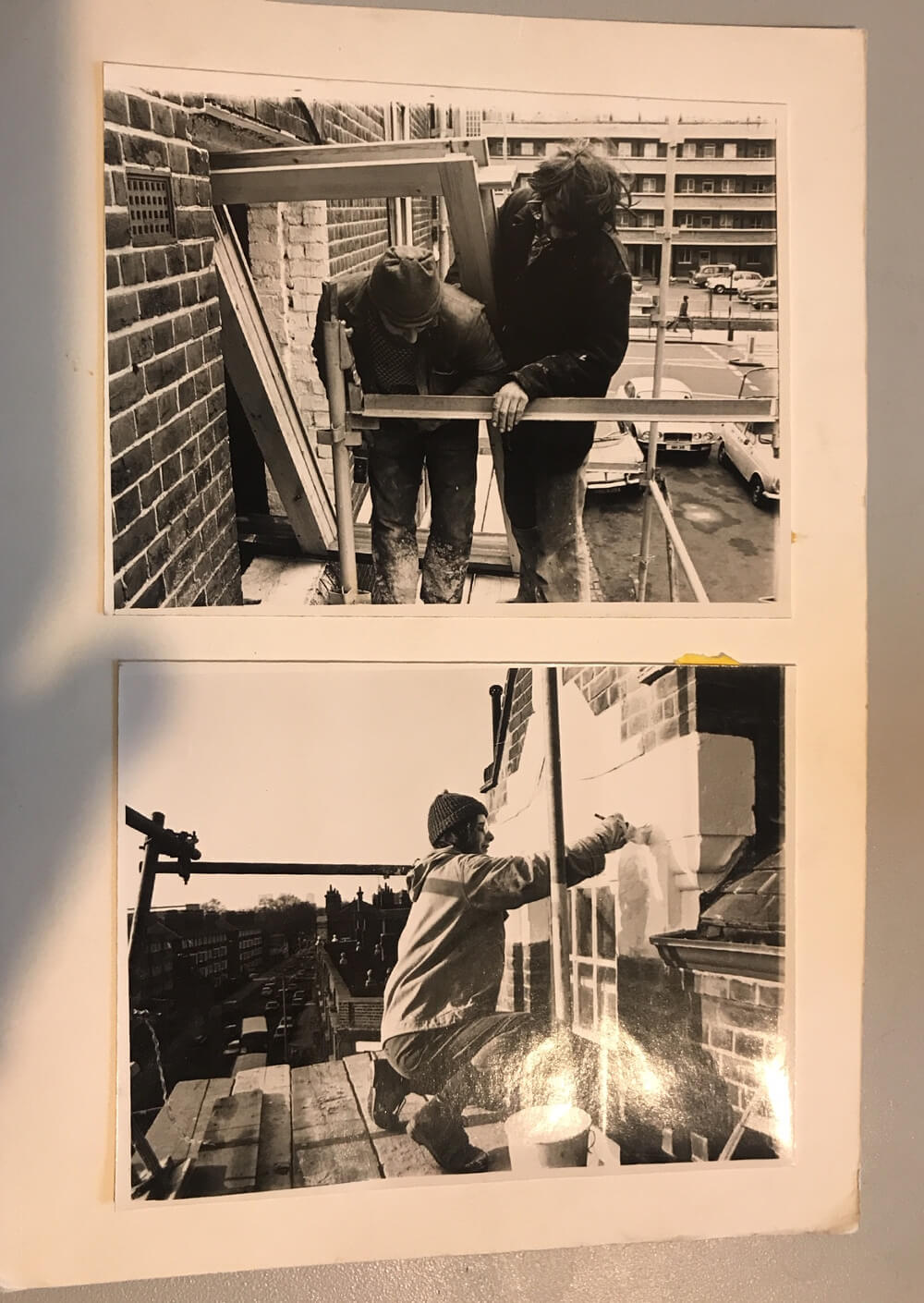

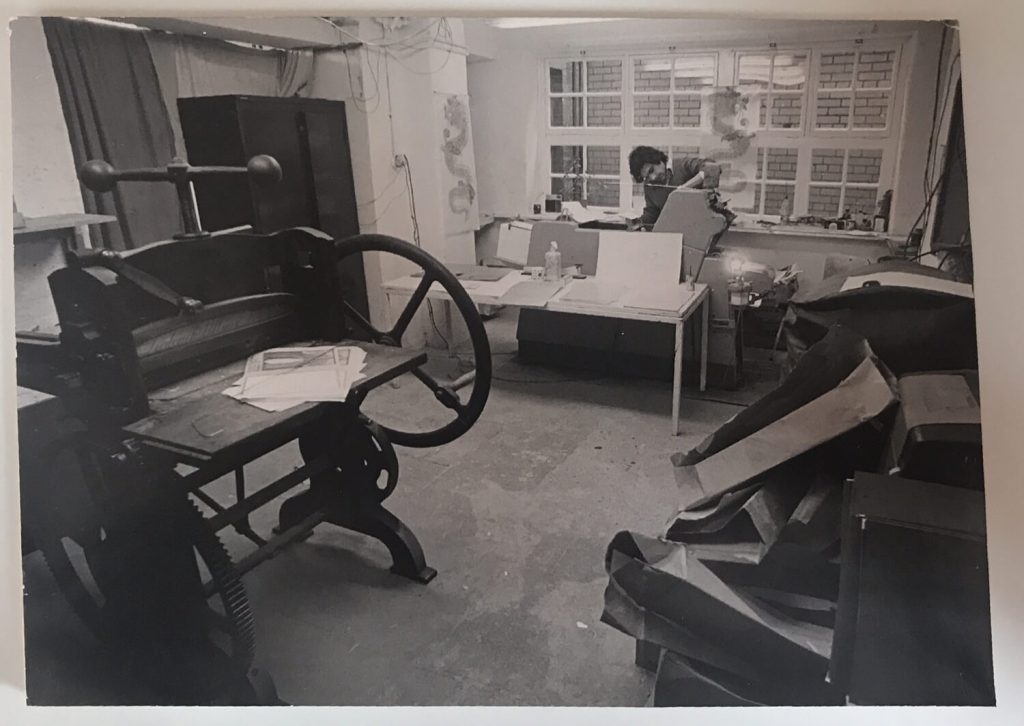

Well, in truth it was more like a Trojan Horse. Whilst the exterior of this Victorian-era fire station was extraordinary, the interior was in a shocking state of disrepair. But, despite the broken windows, the dry rot, the fire damage and the missing floors, the building had potential due to the quality of its construction. They don’t build ‘em like that anymore…

The walls were solid and several feet thick. The roof was intact. There was an abundance of space. This gave Subhuti all the encouragement needed to begin visualising their new home. ‘The engine shed was an immediate shrine room with room for another shrine room behind it and there were three floors for communities.’

So, following successful negotiations with the Greater London Council – an FWBO member’s father had the ear of the gentleman in charge of the letting – they were invited to an interview. Subhuti remembers the conversation that took place:

‘ “How much do you think it’s going to cost to convert?” they asked. I said, “Somewhere between ten and thirty thousand pounds.” They looked a bit embarrassed, so I said, “We’ll be using all our own labour. We’ll use cheap materials. We’ll do it up roughly and then do it up properly later.” They looked acutely embarrassed, so I said, “You’ve obviously done an estimate. How much do you think it’s going to cost?” They said, “Upwards of a hundred and fifty thousand.” ‘

As it turned out even the GLC’s estimate was considerably lower than the eventual cost of renovation, which was just as well given the FWBO only had around ten thousand pounds in a trust fund. But this was a foot in the door. The GLC approved their application and even threw in a 12-month rent free period for the renovation – this is the time period Subhuti considered would be enough to get the job done.

The workforce

Perhaps a group of well-funded, highly skilled, and experienced tradesmen could have transformed this space in a year. But that’s not what the group was. This was a group of young anarchists. They were middle-class art graduates. They had little experience of the working world, let alone the world of manual labour. Incredibly, however, lady luck was to intervene once more.

One of the members, named Atula, was a skilled carpenter and builder. Following a great deal of persuasion and encouragement, and much deliberation, he agreed to take up the post of foreman. This meant there was now someone with experience and know-how leading this group of enthusiasm-rich, skills-poor young Buddhists.

Atula wasn’t the only character to enrich this story and drive the narrative forward. Another influence on proceedings was Morishita, a Japanese monk. This was a man with a shady past. Once a member of the Japanese mafia, known as the Yakuza, Morishita had turned his back on a life of violence and extorsion in exchange for enlightenment. His job within the group was to go to Roman Road Market at the end of each day and collect leftovers to feed the apprentice tradesmen.

Eventually, Morishita became a bit of a local celebrity, especially among the children of Globe Town and Bow. When they spotted this tattooed former gangster making his way around the neighbourhood, they would get incredibly excited, shouting and cheering as they marched behind him.

However, even with well-intentioned characters such as Atula and Morishita on the firm, the challenges of a project on this scale made for a fractious relationship between the workers at times. All living on site, it was a perfect storm of young men with limited skills, working in difficult conditions with little in the way of incentive.

Despite the best efforts of Subhuti, morale began to plummet due to the seemingly insurmountable workload. It was time for another stroke of good fortune.

The turning point

The 1970s is widely known as a decade of rising unemployment. By the end of the decade, the number of people out of work had risen to over 2 million. To tackle this, initiatives to get people back into work were created. The Job Creation Scheme was a status awarded to projects that provided employment for local people. And the FWBO managed to bag this status. This was a real coup for them, and a turning point for the project.

This status came with funding from the local authority, and it meant the existing workers were now being paid in exchange for their labour. Furthermore, they could also expand their workforce, employing local people from Globe Town, Bow, and Bethnal Green to really light a fire under proceedings.

Providing work for local people proved to be mutually beneficial, as Subhuti remembers, ‘Some were coming to us because they were interested in Buddhism, but most were just off the dole list.’ And despite the injection of cash and new workers, the commitment to the community, or the ‘Sangha’ in Buddhism, was still paramount, ‘So, that gave us the funding and the community members all gave in their pay, so we then had the extra money we needed. People were getting minimum wage, but most of it they just put into the common kitty.’

This community interest extended beyond employing local people. As renovation drew ever closer to completion, Subhuti began to set up ‘right livelihood’ businesses. Nowadays we’d know them as social enterprises – co-operatives operated by the community for the community.

These businesses included Friends’ Foods (remember?), Jambala Bookshop and Evolution Craft Shop. And they’ve served the community for many years, providing members of the LBC with a livelihood that is ethical, creative and productive, whilst also delivering services to the local population.

But even though many of these businesses are no longer in existence, as Subhuti theorises ‘…many of our right livelihood businesses have disappeared as the surrounding economic environment got tougher…,’ their influence can be seen in the local area today.

The lasting local and global impact

In transforming their new home – their Sukhavati or ‘Pure Land’ as the building came to be known – they in turn were transformed as an organisation.

The idea of the Dharma involves ‘the path of the higher evolution of the individual.’ In other words, it is the journey of perpetual self-improvement. And through the struggle involved in this monumental project, the members, the building and the wider community went through an evolution aligned with this idea.

The London Buddhist Centre opened its doors in 1978. And from its base in Globe Town, the FWBO (since renamed the Triratna Buddhist Community) spread their message of the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha as far as New Zealand in the east and America in the west.

Forty years later the centre teaches meditation and Buddhism in a way that is relevant to modern life. It is central to Buddhism locally and to its global network.

The organisation’s lasting impact, then, owes a great deal to the Old Bethnal Green Fire Station and the group of rag tag Buddhists that transformed it.

If you enjoyed this piece you may like our article about why Globe Town is the wellbeing mecca of London