London’s East End book review: A guide for family and local historians by Jonathan Oates

London’s East End is a thoroughly researched and fascinating book aimed specifically at readers who are looking into their East End family history. Its documentation of how the East End has transformed from market gardens to slums will fascinate local historians too.

East London was a very densely populated area from the mid-nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth and so many people researching ancestors will find they lived in East London. Jonathan Oates, an experienced archivist and historian who has written several books on family history, crime and local history, explains how to go about discovering more about them.

Medieval East London

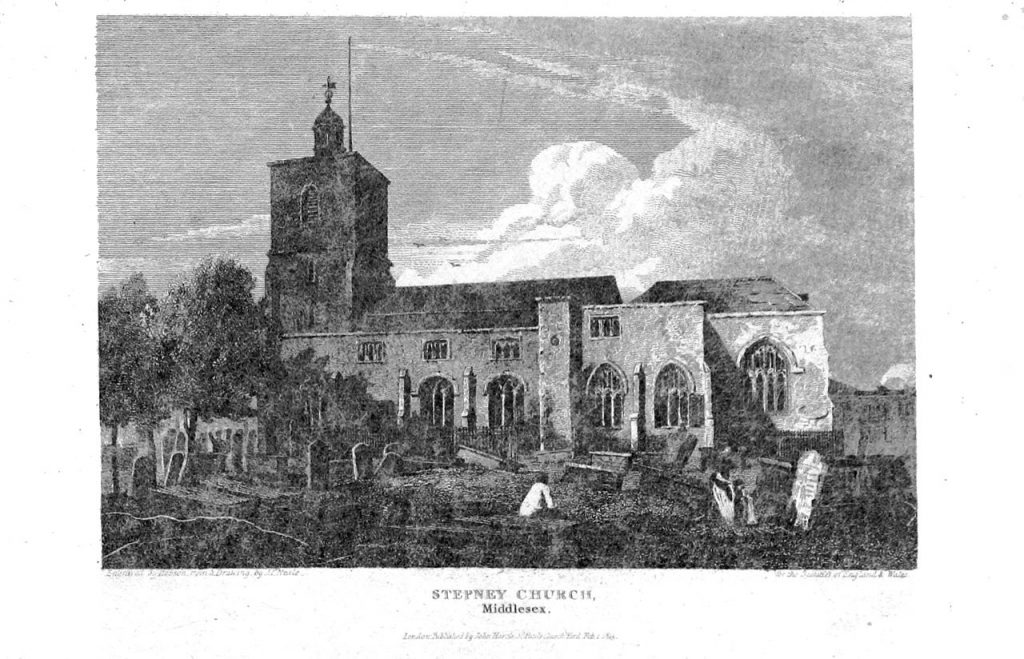

The author describes how the area we now know as East London was built up over the years, starting with the medieval East End. The first fixed settlements arose after the Romans left, and Stepney was the largest area. St Dunstan’s Church was the centre of Stepney, and was part of the ancient manor held by the bishop of London which was recorded in the Domesday book of 1086.

Bethnal Green, Whitechapel and Mile End in medieval times

Bethnal Green was one of the hamlets of the parish of Stepney, as was Whitechapel (named after a white chapel that once stood there). To the east of Spitalfields, a mile along the main road to Essex, was Mile End, which at that time attracted the wealthy who lived in large, grand houses around the manorial common land ( the meeting place where Wat Tyler’s rebels in 1381 tried to overthrow the monarchy). All these ‘hamlets’ were surrounded by woods, field and open land.

Bow, Bromley, Wapping, Ratcliff, Shadwell, Limehouse and Poplar

Bow and Bromley were to the East, both with crossings of the Lea as the road ran from London to Colchester. Bromley grew up around a mediaeval nunnery. The first stone bridge in England was built there after Henry I’s queen nearly drowned when crossing the ford. To the south, lay a number of hamlets on the North side of the Thames: Wapping (named for the Saxon Waeppa), Ratcliff, Shadwell, Limehouse (named for its lime kilns) and Poplar, all linked by a road known as the ‘High Way’ because it was on higher ground than the riverside marshes).

Spitalfields and Mile End in the eighteenth century

Oates goes on to describe how all these hamlets slowly became small towns in the 1700s, as London started to spread eastwards. However, there were still a lot of market gardens, farms and open land in these areas. Spitalfields, with its silk industry, boosted by the arrival of the Huguenot refugees, and Mile End, with its merchants, were still fashionable addresses. Immigrants, mainly Jewish and Irish at this period, started arriving in East London. The shipyards and docks that were built at this time also brought money and jobs with them.

The nineteenth century and the rise of poverty in the East End

As the nineteenth century progressed East London became known as the home of the poor and nearly all of its market gardens and common land disappeared, giving in to urban sprawl (although Victoria Park was created by the government in 1845 to give some relief). It also became far more crowded: the population in 1801 was 142,000 and by the end of the nineteenth century it was almost 600,000.

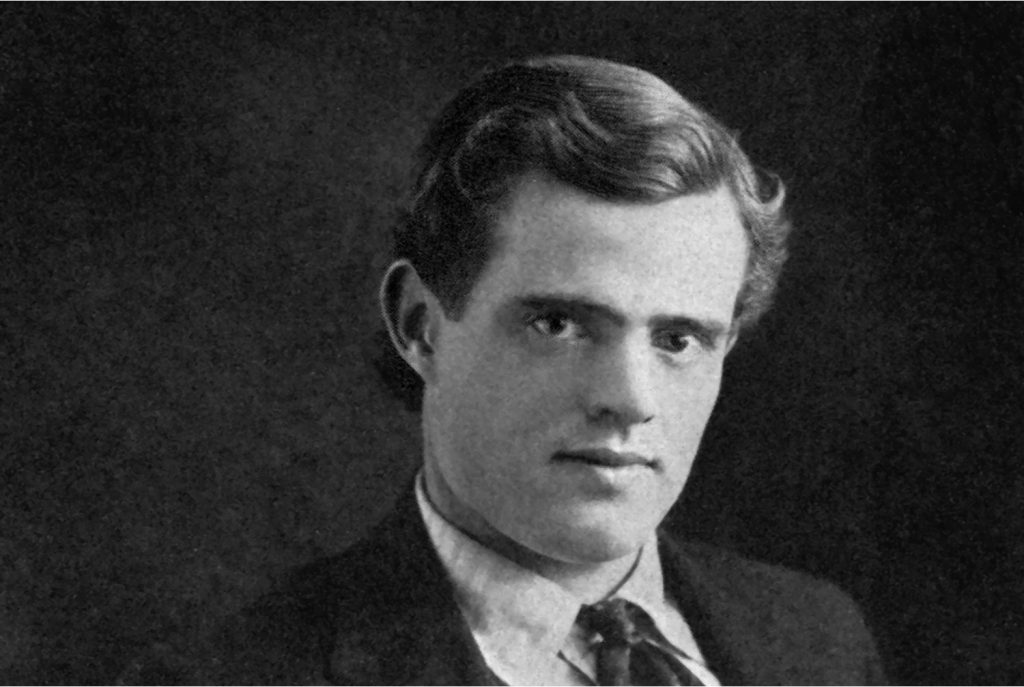

This type of overcrowding led to slum districts, for example in Bethnal Green, and national concern led to various charities trying to make a difference in East London. Silk weaving was in decline and this type of skilled work was replaced by jobs like making matchsticks in the Bryant and May factory, scene of the famous Matchgirl strike, which is discussed by the author in his chapter ‘Working Lives in the East End’. By the end of the 19th Century, Jack London, a visiting American author, described East Londoners as ‘People of the Abyss’.

The following chapters of the book look at different ways historians can trace information about ancestors in the borough and as a result become narrower in focus. However, there are some fascinating facts to be learned.

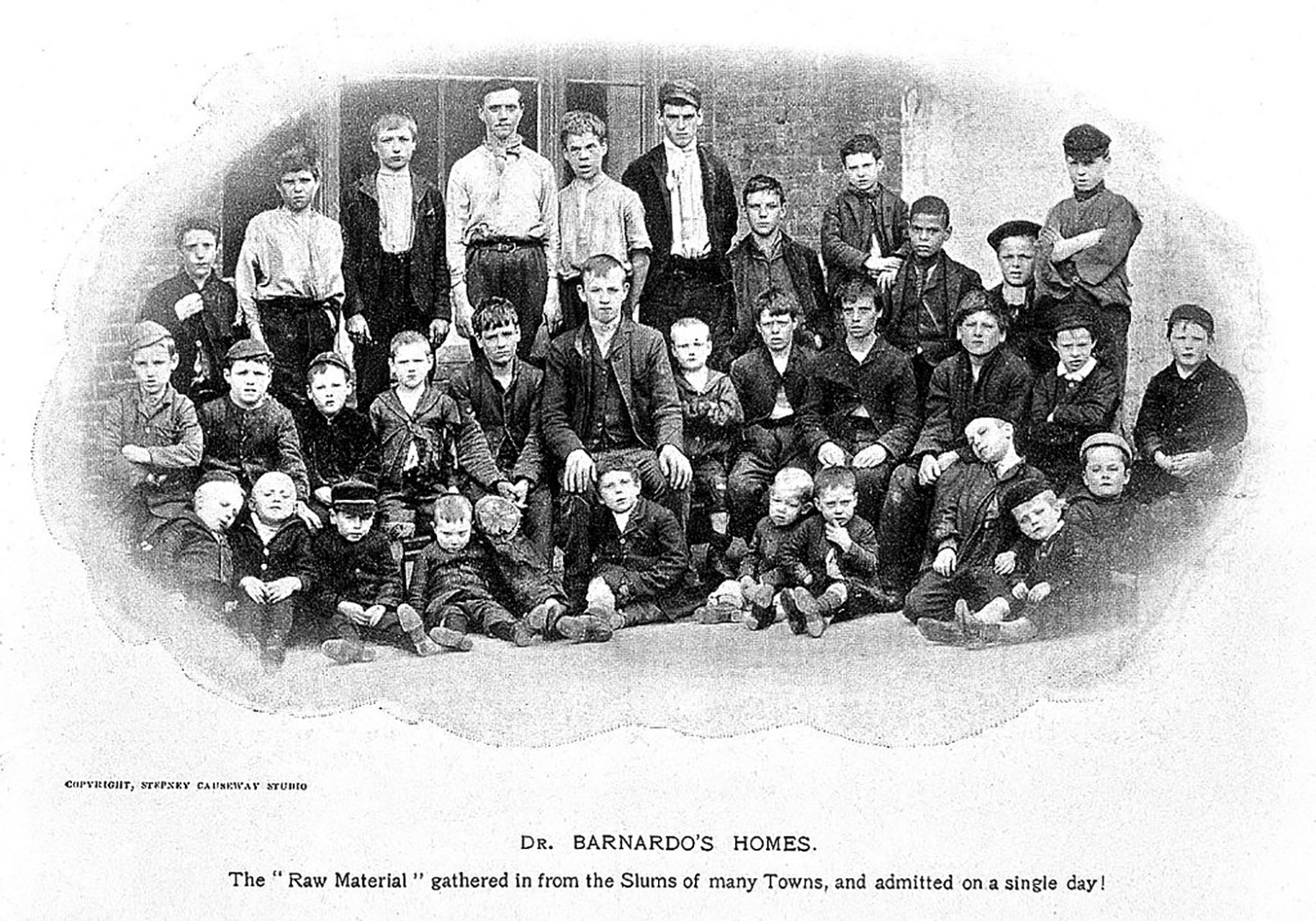

Workhouses and children’s homes

One chapter explains the history of workhouses and orphanages: usually feared by everyone, but perhaps slightly better than the street. Dr Barnardo’s children’s homes were started by the young Irish doctor Dr Barnardo when he saw children sleeping rough in Stepney. The Salvation Army, started by William Booth, and Toynbee Hall, founded by the Revd Samuel Barnett, both tried to improve the lives of the poor.

Crime

Many Eastenders ended up on the wrong side of the law and court records give a fascinating, and sometimes rather sad, insight into their lives. Records from 1764 describe one man stealing another man’s sheep from his garden in Poplar, a crime for which he was sentenced to death (the sheep was found headless in a ditch).

In 1829, the Metropolitan police were formed. Police records from these times give a vivid picture into what it might have been like to live in East London at the time, as do newspapers. A newspaper record of 1865 describes 28-year-old Sophie Field, a ‘land shark’, who pickpocketed Robert Burns, a sailor, in Whitechapel. He was so drunk he didn’t notice the crime but another man witnessed it and ‘gave her up’. Thankfully Sophie was only imprisoned as punishment.

The history of immigration in East London

A chapter on immigration has some great advice for people trying to trace ancestors. Jewish people have lived in East London since the 17th century and their history, especially in Spitalfields, Bethnal Green and Whitechapel, is well-recorded. The Irish settled first in Bow and Bromley, and later in Ratcliff, Wapping and Shadwell – Catholic church and school records are the best source of information for them.

The author also discusses the history of Germans in Stepney, the Chinese community (mainly based in Limehouse) and later in the twentieth century, Bangladeshi people who settled in Spitalfields. It’s a portrait of an area in constant flux as people arrived and left and shows how communities were established at different times in different parts of East London.

All in all, this book is a very well-researched insight into the lives of East Enders of the past. It’s not aimed quite so much at the general reader as to people specifically searching for information about the area’s history, and as a result can be a little dry in places: the lack of colour photos is also a shame, as it would have given the book more visual appeal.

However, there is more than enough here to keep the amateur historian or family history sleuth intrigued and occupied for a very long time. A useful Places to See and Visit section explains how to put some flesh on history’s bones, and there are a great many links and signposts to more archives and resources.

You can buy London’s East End by Jonathan Oates from Wordery here

If you enjoyed this article, you might like to read more about Dr Barnardo’s Childrens’ homes

If you are researching family in East London, you might like to join our Facebook groups Living in Bow and Living in Globe Town