Sir Charles Morgan: The history behind Bow’s Welsh connection

What does an industrial town in south Wales, a Welsh aristocrat, and Bow all have in common? The answer is not as obscure as it first may seem…

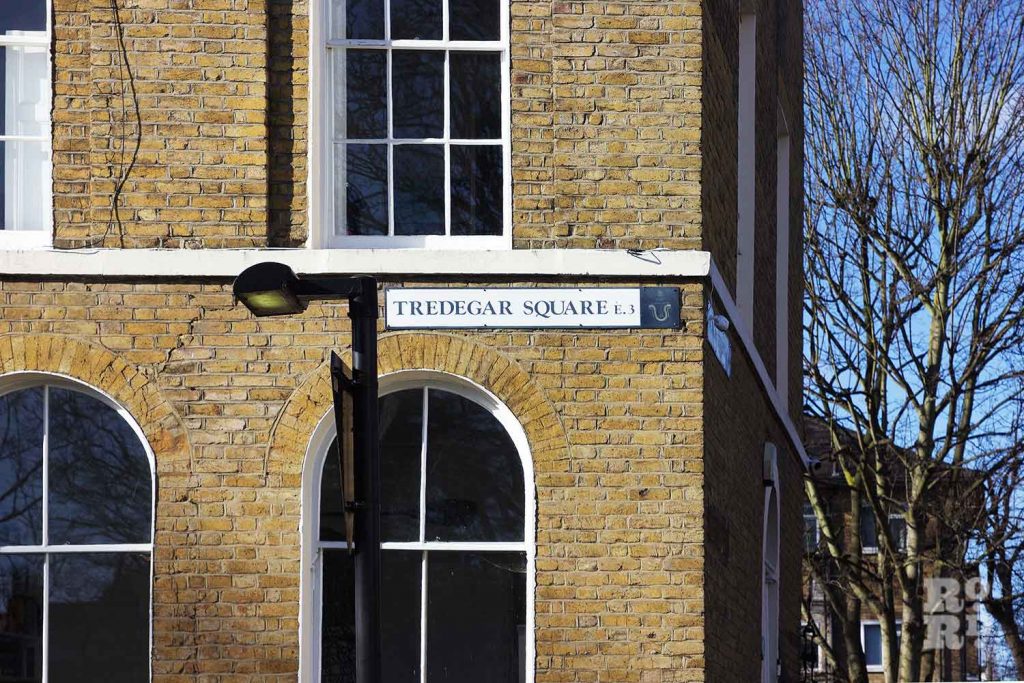

Set back from the melee of Mile End Road and Bow Road, with its grand regency style sandy-hued homes, looming astragal windows, and jet-black steel railings enveloping the peaceful gardens in the centre, Tredegar Square is one of London’s finest Georgian constructions.

The Conservation Area, which is celebrating its 50th year, also includes Tredegar Terrace, Morgan Street, Rhondda Grove and Aberavon Road. There are also our two traditional East End locals, The Morgan Arms and The Lord Tredegar, which take their names from the area. While these street names feel as familiar to residents as their own front doors, have you ever wondered where these names actually come from?

These street names were taken from, or rather were bestowed upon Bow, by Sir Charles Morgan, a Welsh aristocrat living some 170 miles west of East London, in Wales. While locals may now pronounce the area as ‘Tred-a-gah’, in Wales it is pronounced (and no doubt Sir Charles Morgan would have too) as ‘Tred-eager’.

Mile End’s Morgan

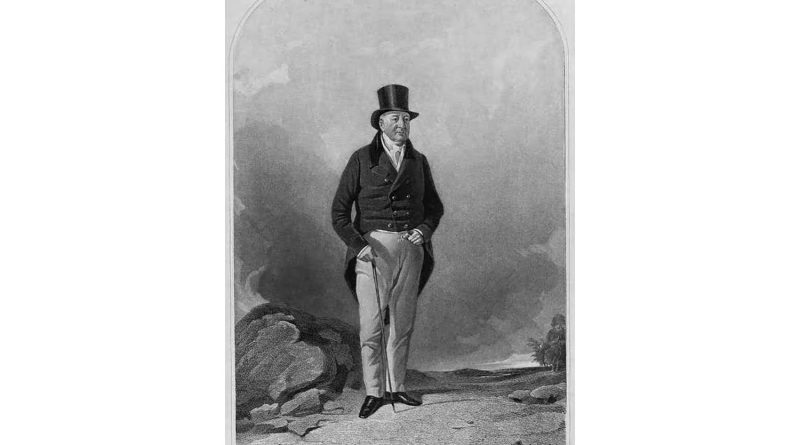

Born in 1760 into an established landed-gentry Welsh family, Sir Charles Morgan was brought up on his family’s estate, Tredegar House, near Newport in South Wales.

Morgan’s young adult life started off in the way which was typical of young men seeking travel and adventure in his era: he entered the army aged just 17 in 1777. The first shots of the American War of Independence had been fired the previous year and the young Morgan was promoted quickly to the level of lieutenant and captain.

In October 1781, he was taken prisoner of war in Virginia by the American revolutionaries. Little is known about what happened to him between then and when the war ended in 1783, but we know that Morgan must have returned to Wales by the mid-1780s because, by 1787, he was elected as Member of Parliament for the borough of Brecon in south Wales.

Morgan was Member of Parliament for most of his adult life, only retiring from Parliament in 1831, aged 71. In his time as MP and local landowner, he did much to promote agriculture in south Wales. He established the largest cattle market in the country as well as setting up an annual cattle fair at Tredegar estate. In true Victoria-style benevolent paternalism, he gave away around £500 of silver and prize money every year to winning cattle farmers.

He was not, however, without his critics: according to one of his political opponents, Morgan was ‘a handsome little man… possessed of great power’, which he deployed to further his own familial interests. With classic 19th-century nepotism at play, he sought to preserve one of his parliamentary seats for his sons, and continually sought to strengthen alliances with other local landowners to increase his and his family’s political and financial influence.

But it was Morgan’s increasing wealth and power that brought him to Mile End and where he left his legacy, which has imprinted itself on the very streets on which we walk.

Welsh street names in the East End

By the time Morgan was 60, in 1820, through politics and financial investments from his Tredegar estate, he had an income of £40,000 a year, around £3.9m in today’s money.

With such accumulated wealth, Morgan sought business ventures outside of Wales and soon became involved with the Stepney estate’s owners, the Colebrookes. He entered an arrangement with them whereby Morgan would use his vast income to develop the area of Mile End and Bow.

He required a private act to do so. Already highly familiar with the political system, it was granted by King George IV in 1824.

Work started quickly and, by the 1830s, much of Tredegar Square, the villas on Rhondda Grove, the houses at the eastern end of Morgan Street, and the main western terrace of Aberavon Road were built.

All these names have links to Morgan’s Welsh heritage – he opted to name the most opulent residential areas, Tredegar, as a nod to where his wealth came from, namely his family’s estate as well as from the industrial town of Tredegar where The Tredegar Iron Company was based.

The Company was the Morgans’ family’s tenants and the family did well out of leasing part of the estate to the Company. While it’s unclear why Rhondda and Aberavon were chosen as names for other streets, it may solely be due to the fact they were familiar and meaningful marks to Morgan on the landscape of his native south Wales.

An elderly man, Morgan died aged 86 in 1846. Sadly, he wouldn’t live to see the site developed further: a year after his death, new properties were built to the north of Morgan Street, and by the late 1880s, the area had become built up, so much so that the aesthetics of Tredegar Square and its surrounding streets live on in nearly the exact condition in which it was built.

By the mid-20th century through bombing damage during the war, and general neglect, the square and its surrounding streets suffered the lowest point in their history. Primed for demolition by property developers under the pretence that they would ‘improve the area’ by constructing the square from scratch, members of the Mile End Old Town Residents’ Association fought passionately against these plans. It was then that the Tredegar Square Conservation Area was established in 1971.

Despite almost 170 miles separating Tredegar in Wales with Tredegar Square in London, without the future residents’ determination, who knows if Morgan’s legacy would have been kept. Without him, we wouldn’t have had such a beautiful square which makes up one of the most impressive in London today.

If you enjoyed reading this article, then take a look the history and the designer behind Meath Gardens.