The history of Bow Station, the ‘St Pancras’ of Bow

Little remains of the grand Bow Station on Bow Road that operated from 1850 to 1944, although you’ve probably walked past it many times before. We took a look at the fascinating, and empowering, history of Bow’s ‘St Pancras’.

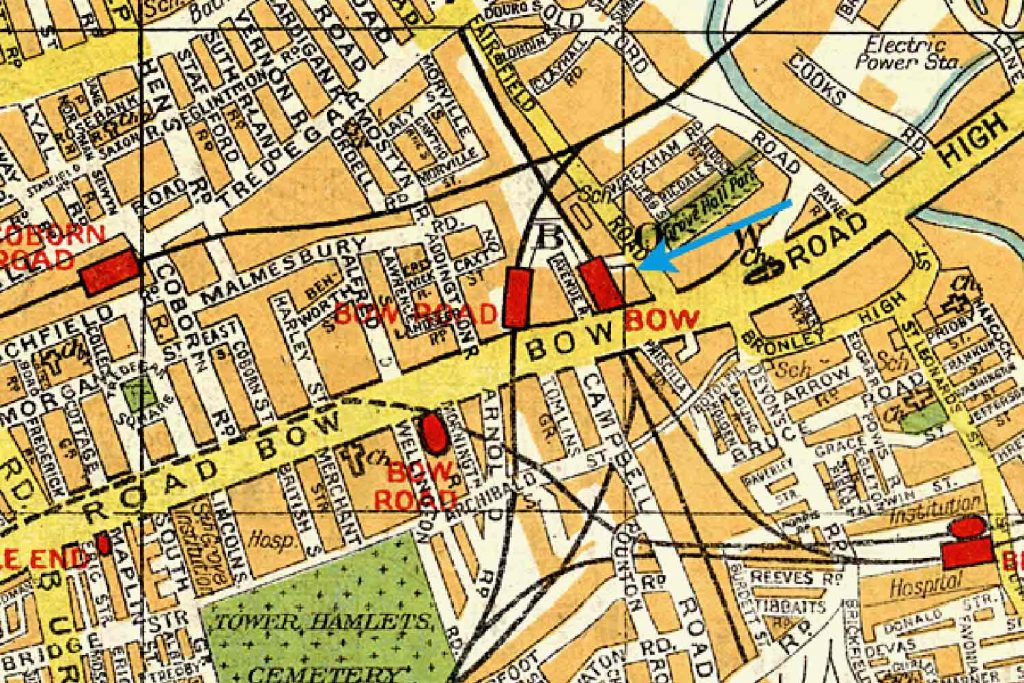

Bow Road had its fair share of railway stations. It might surprise you that there were two within meters of each other: the lesser-known Bow Road Station and the grander Bow Station, neither to be confused with Bow Road tube station on the opposite side of the road.

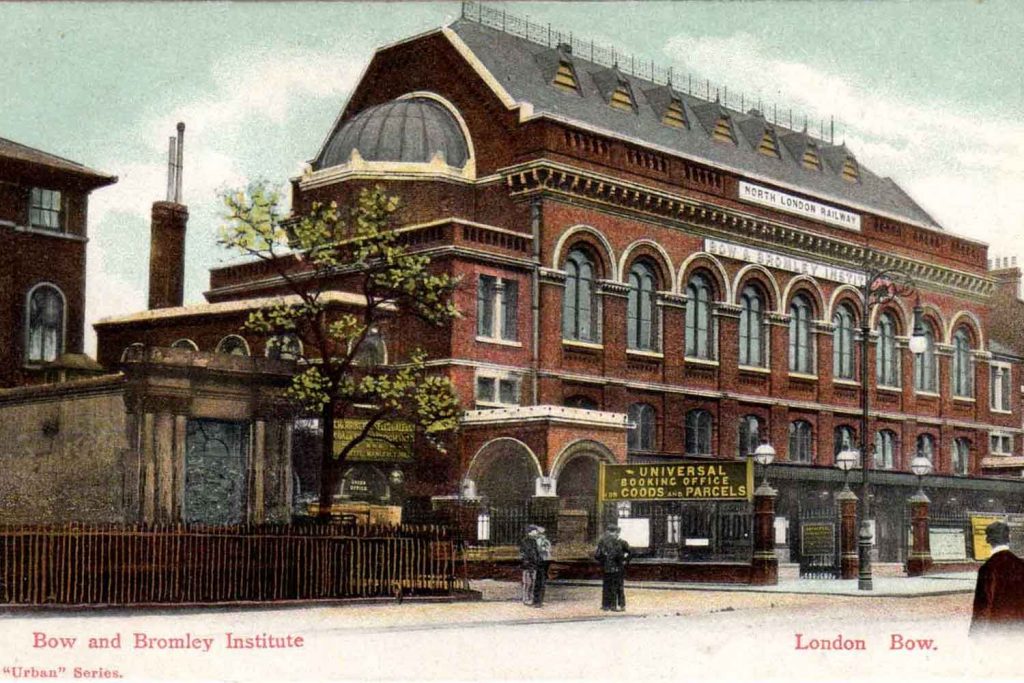

Bow Station was located where the vehicle rental service, Enterprise Cars, is currently found. Considered a feat of Victorian architecture, this three-platformed station lay beneath a large concert hall that playwright George Bernard Shaw frequented.

On 26 September, 1850, Bow Station was opened by the East and West India Docks and Birmingham Junction Railway company. This line was initially intended to transport freight goods only, as the London & Birmingham Railway wished to reach the Thames’ docks. But the demand from people was there, and a passenger service was also included in the offset.

From Bow Station, travellers could take the North London line to its terminus in Poplar, or ride the Great Eastern Service to Fenchurch Street with through trains – a journey that changes operator or provider during the same trip on the same line – to Southend and a shuttle to Plaistow.

Just three years later, the line changed name to the pithier North London Railway and a connection was built at Hackney Wick in 1854, as well as at Victoria Park in 1856.

An impressively sized station for its time, its street-level ticketing office was expansive, offering both waiting rooms and catering services to customers. And on 26 March, 1870, the booking office was replaced with a much bigger building.

But the most spectacular features of all lay outside and on top of Bow Station: the 100-feet-long, 40-feet-wide concert hall and an ornate fountain commemorating the Bryant & May factory’s important intervention in the nation’s taxes.

Bryant & May fountain celebrating match tax victory

In 1871, the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, Robert Lowe, tried to introduce a new tax on matches: ½ a penny per 100 matches. The Times wrote that the tax was a ‘reactionary proposal’ that would disproportionately impact the poor; the workers, and even Queen Victoria, passionately agreed.

Matchmaking companies were appalled by the government’s proposals. So they got organised. On 23 April, 3,000 workers attended a mass meeting in Victoria Park, most of whom worked at Bow’s Bryant & May matchstick factory. Collectively, they decided to march to the Houses of Parliament with a petition and sure enough, the next day several thousand people set off from Bow Road.

The demonstrators were mostly working-class women aged as young as 13 up to the age of 20 and mostly from Bryant & May. The protesters were stopped by police when they reached Mile End Road.

The Times reported that the police had ‘by their hard usage of the matchmakers and spectators, converted what was before not an ill-behaved gathering into a resisting, howling mob’.

This didn’t deter the determined protesters though. Some split off from the main group, while others simply continued on, pushing past the line of police; 10,000 people made it to Westminster.

On the same day that the match-factory workers gathered in Victoria Park, Queen Victoria wrote to the Prime Minister professing her aversion to the tax. She stated that the tax would ‘be felt by all classes to whom matches have become a necessity of life… [and] will in fact only be severely felt by the poor, which would be very wrong and most impolitic at the present moment.’ The tax proposal was withdrawn the day after the march.

To pay tribute to their victory, employees of Bryant & May’s firm paid to erect a 30-feet-high fountain outside Bow Station. When Bow Road was widened, this fountain was removed and is now remembered by a plaque.

Bow Station’s concert hall: from George Bernard Shaw to Bow Palais

©️ Disused Stations

The impressive concert hall above the station was also a testament to Victorian life in Bow. It went through many changes in ownership in its time, from the East London Technical College to The Salvation Army, but it was first used by The Bromley & Bow Institute as a public cultural centre where music concerts were held for up to 1,200 people.

These concerts attracted none other than the esteemed playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw, who, in February 1889 was told by his editor to review a concert in Bow, a place he had previously never heard of.

In Shaw’s words, he recalls the excitement of such an ‘intrepid’ experience as venturing to the East of London.

‘Snatching the tickets from the editor’s desk, I hastily ran home to get my revolver as a precaution during my hazardous voyage to the East End.’

‘Then I dashed away to Broad Street, and asked the booking-clerk whether he knew of a place called Bow. He was evidently a man of extraordinary nerve, for he handed me a ticket without any sign of surprise, as if a voyage to Bow were the most commonplace event possible’.

But evidently when Shaw arrived at The Bromley & Bow Institute, his uncertainty towards Bow radically changed, for the better.

Praising the concerts held above Bow Station, Shaw wrote: ‘the most accomplished English and foreign performers appear[ed], the charges for admission being sixpence and threepence. A means is hereby provided for enabling the humblest classes to become acquainted with at least one variety of the best music, performed in the best manner, at a nominal cost; and it is cheering to know that the movement has been attended by unqualified success.’

‘The work here, it should be noted, is carried out on strictly businesslike principles, without any pretence at philanthropy or any intrusion of the goody-goody element. Herein, we believe, lies the secret of its success.’

Bow Station during the World Wars

Below the lauded concert hall, the station met a similar fate to other railways in the area. Passengers on the line declined after WWI and, during the WWII bombings, the service was suspended altogether. BowSstation finally met its end in 1945, when it was damaged beyond salvation by a V1 ‘flying bomb’.

However, the hall continued to serve the public, and was renamed the Bow Palais. It became particularly popular with Irish bands, dancers and nurses from St Andrew’s Hospital. In 1956, the hall was severely damaged by a fire, which led it to be closed and demolished by 1965.

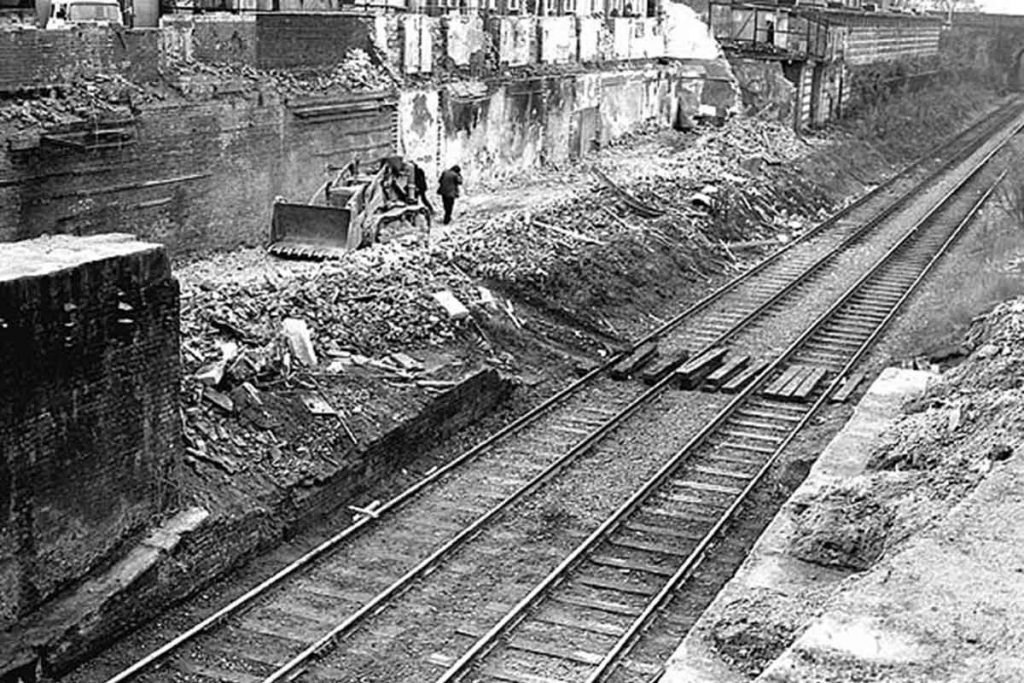

The final remnants of the station – the platforms and the railway tracks – were finally removed in 1985, apart from a section of the old line to Poplar which is now used by the Docklands Light Railway. Bow Station is now marked with a Bow Heritage Trail plaque.

What, on the surface, appears to be just a majestic-looking station of Bow’s past reveals itself to be much more. From Bryant & May’s workers protesting against a tax reform that would adversely affect the poor, to the Bow and Bromley Institute’s cheap music concerts that allowed many stratas of society to attend, Bow Station is symbolic of the East End’s consciousness towards socio-economic inequality.

©️ Disused Stations

©️ Disused Stations

Complete the station trilogy and uncover the history of Bow Road tube station and the other Bow Road railway station.