What does the word Cockney actually mean?

Nowadays, we all have an idea of the meaning of the word Cockney, but we’ve discovered that the history of the famous moniker is far from linear.

Whether you subscribe to the traditional definition that a Cockney is someone born within the sound of St Mary-le-Bow’s bells, or feel that being a Cockney is more of a state of mind, the word Cockney evokes strong connotations.

Cockneys exhibit wit, tenacity, and charm, as evidenced by famous individuals such as Charlie Chaplin, Michael Caine, Alex Scott, and Micky Flanagan.

But what if we told you that the word Cockney was originally synonymous with being weak and sheltered? Or worse still, a defective egg?

Medieval Origins

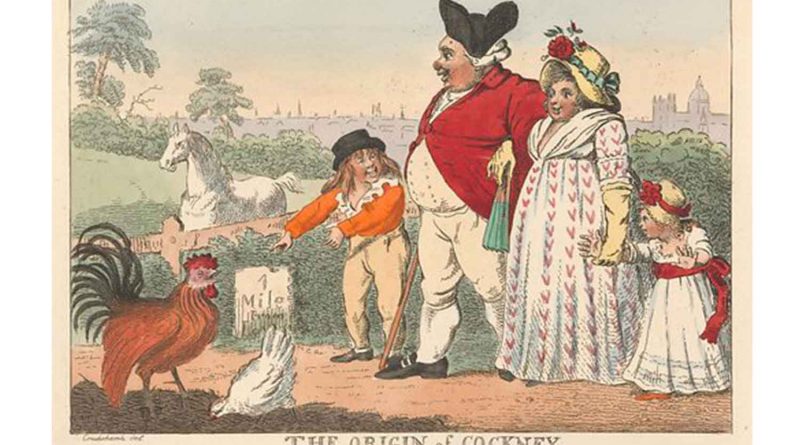

The word ‘cokeneye’ was first recorded in 1362 by William Langland in his narrative poem, Piers Plowman. In this context, the word ‘cokeneye’ referred to a rooster’s egg, aka something that doesn’t exist.

In medieval England, the word was primarily used as an insult. Referring to something as an egg laid by a rooster could invariably indicate that it was useless, imaginary, or inadequate.

A few decades later, Chaucer took the insult further, when he used the word in The Reeve’s Tale to refer to someone as a delicate and inexperienced weakling (a far cry from its modern association with the grit and determination of East Enders).

Outside of its use as a medieval insult, the spelling of the word Cockney as we now know it was also used to refer to the mythical realm of Cockaigne. Cockaigne was described as a land of comfort and luxury, where rivers of wine flowed, houses were built of cake and sugar, and all of a person’s whims and desires were easily met. Not too far off from modern-day Bow!

Urban Associations

In the 16th century, the meaning of the word cockney Cockney was still being used to describe people as overindulgent milksops, with Shakespeare even employing the insult in Twelfth Night and King Lear.

While the first work that associated the word ‘cokney’ with city-dwellers was Robert Whittington’s 1520 Vulgaria, it wasn’t until the 17th century that this association permeated the mainstream consciousness.

Londiners, and all within the sound of Bow-bell, are in reproch called Cocknies, and eaters of buttered tostes.

Fynes Moryson, 1617

In 1600, Samuel Rowland first recorded the use of the phrase ‘Bowe-bell Cockney’ to refer to a Londoner. Aside from highlighting the lasting connection between Cockneys and the bells at St Mary-le-Bow Church in Cheapside, Rowland’s coining of the phrase established Cockney as a term for city dwellers.

Though it had finally come closer to its modern definition, the word Cockney still maintained its insulting connotations. It was primarily used by people in the countryside to show their disdain for soft and spoiled city folk.

In 1617, the travel writer Fynes Moryson wrote: ‘Londiners, and all within the sound of Bow-bell, are in reproch called Cocknies, and eaters of buttered tostes.’ Though seemingly an innocent depiction, the phrase ‘eaters of buttered tostes’ was actually a scathing insult for Londoners who had become pampered and lazy without the hard work of country life. A far cry from the hard graft Cockneys are known for nowadays.

Cockney soon became a term exclusively applied to Londoners, despite its initial use to describe all city dwellers.

Victorian Cockneys

The Victorian era is known for giving us some of the most famous Cockneys in recent history. With characters such as The Pickwick Papers’ Sam Weller and Oliver Twist’s Artful Dodger, the work of Charles Dickens brought the Cockney style of speech into the literary realm.

Though the Cockney style of speech had been depicted in earlier works, including those of both Shakespeare and Swift, it wasn’t until the 19th century that it was classified as a distinctive language. This coincided with the development of Cockney rhyming slang by Victorian costermongers, which remains one of the most ubiquitous features of the Cockney language.

As the modern characteristics of Cockney language and culture entered the mainstream and the term became associated exclusively with the East End, rather than all Londoners, the word became linked with some more unsavoury stereotypes.

In the 19th century, Britain experienced a period of rapid industrialisation that had a profound effect on the lives of the people in the East End. As the population ballooned and many heavy industries established themselves in the surrounding area, the living conditions of the local population deteriorated.

This led to rampant suffering and poverty that forced people to turn to crime and informal practices in order to survive. Many of the modern stereotypes related to Cockneys have links to this period of hardship.

However, it was also during this time that Cockneys became known for their wit and resilience. An 1884 excerpt from Punch magazine sees Mr Punch himself replying to a disgruntled reader with the following words: ‘Having been born within the sound of Bow Bells, he cannot help being a son of Cockaigne, though he is so cosmopolitan as to be able to sympathise with everybody all the world over.’

Punch is referring to himself in the third person and his response expertly marries both the historic connotations of the word Cockney and the unique wit of its denizens.

Modern Cockneys

In the modern world, the meaning of the word Cockney continues to come with a variety of stereotypes, but most people wear the term as a mark of pride. Though not everyone can agree on what a Cockney truly is, its language, culture, and history live on in the East End and beyond.

Local people such as Chris Ross, the Cockney poet, and G Kelly’s Leanne Black continue to serve as reminders of the illustrious history of the term Cockney in our area. We doubt there’s anyone out there who would use the term to refer to someone as weak or spoiled.

If you liked this article, read our piece about how the people of Bow define themselves.