Globe Road’s Craft School: A History of Arts and Crafts in the East End

In the late 19th and early 20th Century, Globe Road was home to a thriving Crafts School which, since 1925, has been memorialised by a small plot of land on Globe Road.

Today, Globe Road’s memorial garden is no more than a forgettable—if not a bit unsightly—piece of land with a few trees, gravestones and a sprinkling of litter.

But it’s a lot nicer than it once was. An article published by the Morning Post in 1839 describes the awful state of the graveyard. Bodies were piled on top of each other in place of a proper burial. The article describes an inspector’s visit to the ground where he was met with a surprising sight.

‘Inspector M’Craw, accompanied by sergeants Parker and Shaw…proceeded to the burial ground in question and as they were about to enter, they met a lad with a bag of bones and a quantity of nails, which he was going to sell.’

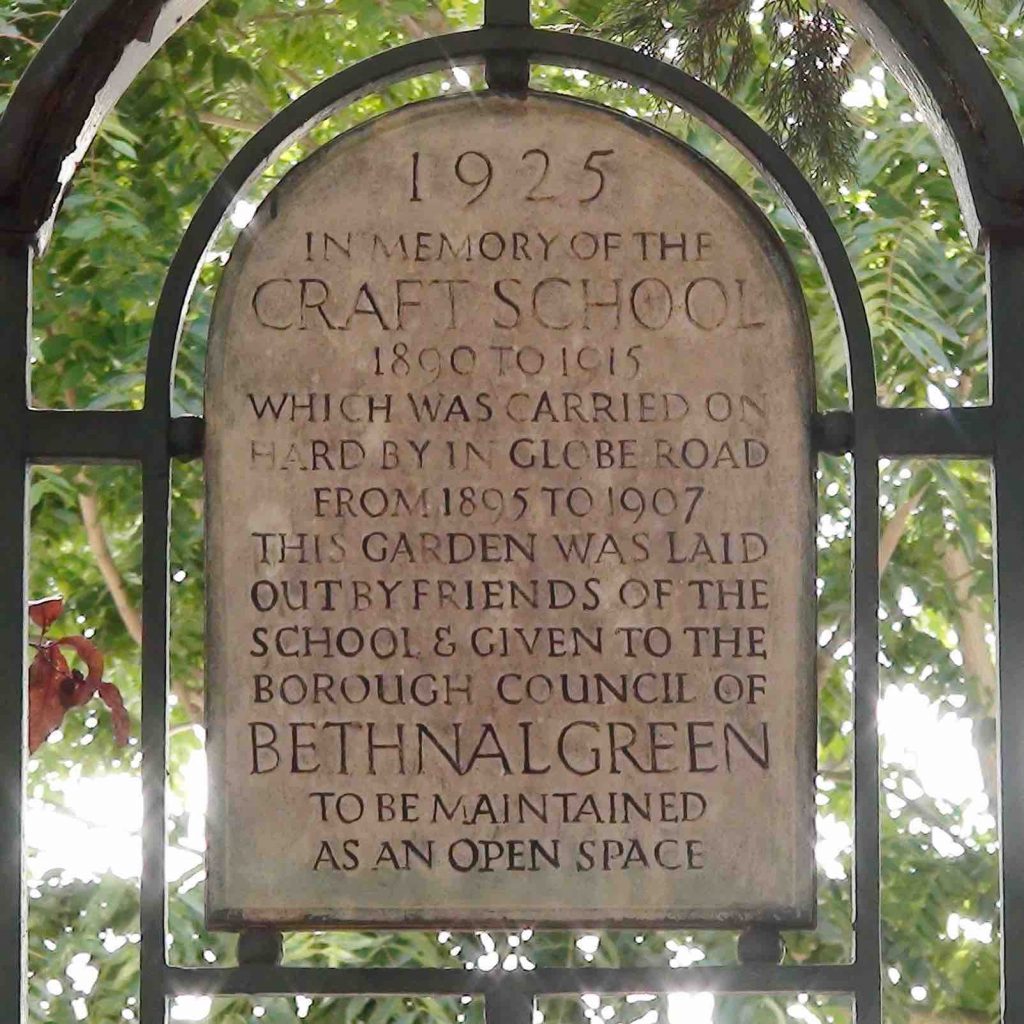

Today, you probably won’t find anyone selling human bones. If you manage to get inside the ground’s locked gates, you will see a plaque above the entrance which reads ‘1925 in memory of the Craft School 1890 to 1915 which was carried on hard by in Globe Road from 1895 to 1907.’ Between these dates, the Craft School played an important role from 137–141 Globe Road by offering education in artistic production to working-class East Enders.

In 1925, the abandoned burial site was transformed from a dumping ground into a memorial garden with little nods towards the Arts and Crafts movement which it memorialises. An example of this is the ring and rose motif on the railings. This references the Ring and Rose Club out of which the Craft School grew.

The garden memorialises the contribution of East Enders to one of the most influential artistic movements of the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries.

The Arts and Crafts movement was a reaction to the industrialisation of object production in the late Nineteenth Century. Proponents of the movement saw this as a de-individualisation of work and a way of dehumanising the everyday.

Mass production meant that the objects that define our sensorial lives, through our constant interaction with them, became impersonal and homogenous. The artists of the Arts and Crafts movement aimed to create a socialist artistic space, albeit with the help of their privilege as upper-class men who faced no discrimination and did not need to work for their living.

This kind of Romantic Socialism depended on the wealth of its followers and was perhaps more of a rich boys’ dream than a real social movement. Today’s East Ender might find this painfully relevant if they know a budding artist unable to make a living from their work. The East End is full of artists but how many can dedicate themselves to their craft without another source of income?

In 1891, the 49 Beaumont Square community opened the Whitechapel Craft School to democratise artistic production. Their vision was that they would educate the working-class residents of the East End and offer them the skills to make useful objects beautiful. They would produce a wide variety of goods from cabinets to jewellery.

Later, In 1896, the Craft School was moved to Globe Road where it existed for more than half of its life. The building was, at the time, an abandoned Catholic Church, creating an atmospheric scene as the students studied and produced beautiful, intricate designs.

Charles Booth was one of the donors whose money helped the school stay in business. He is famous for his poverty maps which indicate London’s poorest areas. A sense of social reform was therefore integral not just to what the school produced but also how it was run, and how it was funded.

While the Craft School was on Globe Road, it was more than just a place to learn artistic techniques. They had sports events and hosted lectures. It was a community hub aiming to uplift the impoverished East End. You can visit Tower Hamlets Archives today and read clippings from early Twentieth Century newspapers that detail the history lectures given at the School.

In one such clipping from the East London Observer, we can sense the importance of the Craft School as a space aiming to regenerate the area.

‘The Craft School in Globe-road where the lecture was given, was in the very heart of old East London memories.’

In 1915, the School was closed. Despite being much-loved by its students, it was subject to the financial pressures of the war. This begs the question of how we approach funding the arts. How do we avoid artistic production being a luxury of good times?

There are still plenty of artistic community events happening in Bow. Though they may not carry the wistful idealism of Romantic Socialism, they allow people who are not artists professionally to produce meaningful objects and come together as a community.

The space today may now be strewn with bits of litter, and mostly abandoned, but it was in an even worse state when it was originally made into a memorial garden. It offers us a reminder that art should be able to come from nothing.

If you enjoyed this article, you might like Charles R. Ashbee’s Guild of Handicraft: the man who brought arts and crafts to the east end.