The Malmesbury Estate: A large village in the heart of Bow

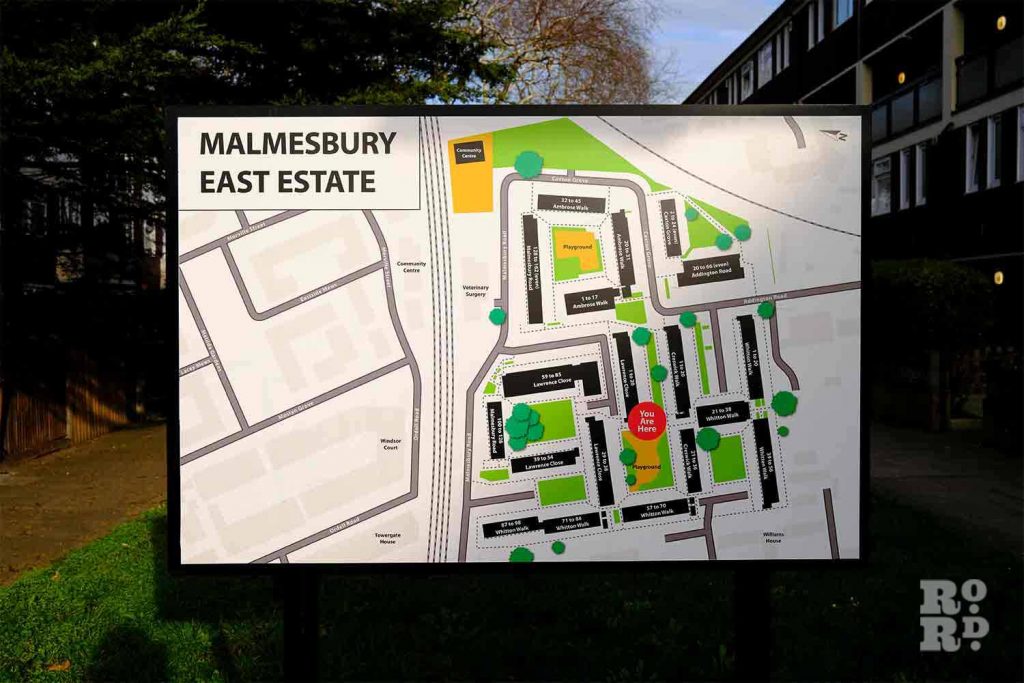

The Malmesbury Estate is a quiet low-rise development that connects Bow’s two halves, and its residents to their community.

The Malmesbury Estate is a tranquil low-rise sprawl, tucked tightly along the Great Eastern Railway line. Brick houses snake around quiet enclosed courtyards, making up a community in the heart of Bow.

The Malmesbury Estate’s construction began fifty years ago in 1974. At the time, a combination of slum clearances, war damages and population growth meant new housing was needed urgently. Both the central and local governments were Labour. It was common practice then for councils to have an architect on staff, so the design of the Malmesbury fell to Borough Architect John D. Hume.

By 1977, when the Malmesbury was completed, almost a third of UK households lived in council housing. As a large amount of housing was needed quickly, many high-rise council estates had been built to meet demand. However, in May of 1968, the Ronan Point estate in Newham catastrophically collapsed due to a gas explosion and low-quality construction.

The tragedy made tenants and councils wary of quickly built high-rises. Councils were also beginning to take more seriously the need for social and communal spaces in housing. As a result, building trends moved away from flats, to low-level terraces and maisonettes with shared spaces such as the Malmesbury Estate.

The Malmesbury Estate is made up of long skinny blocks of flats, with handsome brown brick, blue window accents and tented rooves. Cul-de-sacs wind through the estate, with broader paths cutting through the middle. Most of the houses are arranged in a horse-shoe or L-shape to face inward onto courtyards, gardens or parks. They are between two and four stories, to make up a total of 603 dwellings.

The estate was named after Malmesbury Road, along which it runs. Malmesbury Road was originally two roads, Clarence Road and Clarence Road West. In the 1870s they were merged and re-named after the third earl of Malmesbury, a popular Conservative politician at the time. This was because too many things had been named Clarence.

Interestingly, we found that the portion of Malmesbury Road that was closed during the estate’s construction was illegally moved during the project, appearing ‘magically’ much closer to the railway than before. It is unknown whether the borough architect Mr. Hume had anything to do with this.

Once the estate was open, it quickly filled with many different types of people. If you leaned over your balcony to listen in on the courtyard, it was a coin toss what language you might hear.

As well as local Cockneys, the estate housed migrant communities of Bengalis, Pakistanis, Somalians, Ghanians, Portuguese, Spanish and Italians (to name a few). Migrants were brought to the East End for reasons ranging from fleeing civil war to economic hardship.

Manuel (50), who grew up on the estate said that as a child he grew up with ‘friends from every nation’. He recalled everyone gathering along the train tracks to play ball, with whoever kicked the ball over having to climb onto the tracks to get it (thankfully the railway is now surrounded by high fences). When the ice cream truck came, children would clamour in the courtyard to their parents for coins, and for a moment it would look like it was raining silver he recalls

Manuel moved to the Malmesbury Estate with his parents and sister circa 1978. ‘Everyone knew each other, there was never any trouble,’ he said. People took turns with communal cleaning and listened to their neighbours’ dramas from the balconies. His parents were employed in the busy Mile End Hospital, and he has fond memories of eating with them in the canteen on their lunch breaks.

Built along with the estate is the Caxton Community Centre, created so residents could host events, and named after William Caxton, who first brought printing to England. It is now used mostly as a meeting point for AgeUK East London, a charity working with older people.

There is also the richly storied Harley Grove Sikh Temple, a structure that predates the estate. It was converted from a synagogue to a Sikh Temple in 1977 to reflect the changing demographics of the borough. In 2009, the temple suffered an arson attack that destroyed most of the building’s original structure. It was restored and re-opened in 2013.

Just south of the Malmesbury, residents can squeeze through Tom Thumb’s Arch, a small underpass and one of the few spots where the railway track separating Bow can be bypassed. The arch is named after Tom Thumb, a tiny and mischievous character from English folklore, no bigger than a thumb.

Those who grew up in the area remember the underpass as a popular meeting place during the day, if slightly dodgy at night. Today, the path cutting through the estate via Tom Thumb’s Arch is busy with commuters and school-children. Despite its small size, the arch has a big imprint on memories of the neighbourhood, as so many who grew up in Bow will have passed through it every day.

The arch is predominantly used by people accessing busy Bow Road and its tube and DLR stations. The Bow Church DLR station opened in 1987, as part of the original DLR line from Stratford. The idea was to use London’s by-then disused docklands for public transport.

Another iconic site east of the Malmesbury Estate is the Bryant and May Match Factory, which closed in 1979, marking the end of an era. When it opened in 1861, the factory was the biggest in London. It was the site of the famous London matchgirls strike of 1888. Now it has been converted into luxury housing.

And of course, north of the estate is the famous open-air Roman Road Market. In its heyday, hundreds of locals would have spent their Saturdays shopping at the market and catching up. Beginning in the 90s, increased competition from supermarkets, shopping centres and online marketplaces has reduced the size of Bow’s famous street market, but it still attracts a loyal crowd.

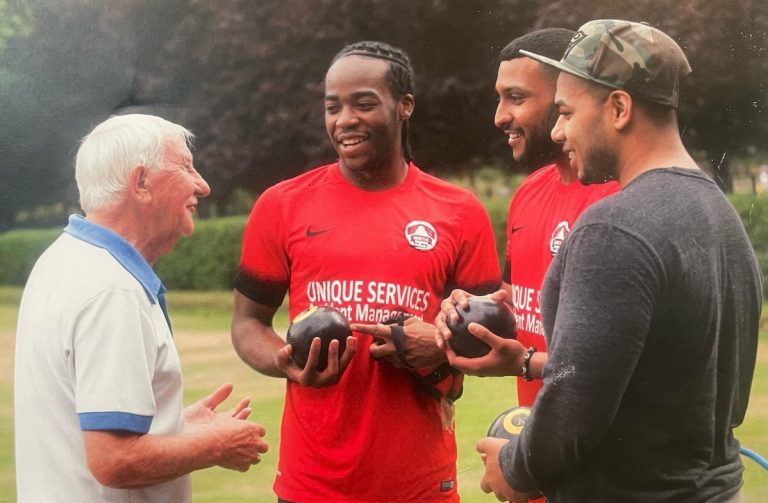

Today, one of the biggest changes to the Malmesbury estate is an increase in green space within its walls. A push from residents and community members has seen projects like the Ambrose Walk Community Garden, which provides greenspace and edible food for residents. Charity Trees for Cities also facilitated a project to increase biodiversity and tree cover in the estate.

With right-to-buy coming into effect in 1980, many of the original residents have bought their flats, and some have been sold on privately. Other flats are still council housing. Those who live on the estate today are a mixture of old and new residents, a new chapter for a 50-year-old community.

Sharing a borough with architectural darlings like the Greenways Estate, the Malmesbury is often overlooked. But the estate is uniquely placed, connecting Bow’s halves. Residents continue to improve the estate, for example with the ‘Bow Colours’ mural, greening initiatives and communal gardens. Thanks to its thoughtful initial design and the care taken by residents over the years, the Malmesbury is a special place to live today.

If you liked this, you may enjoy The history of Greenways Council Estate, a butterfly plan designed for social cohesion