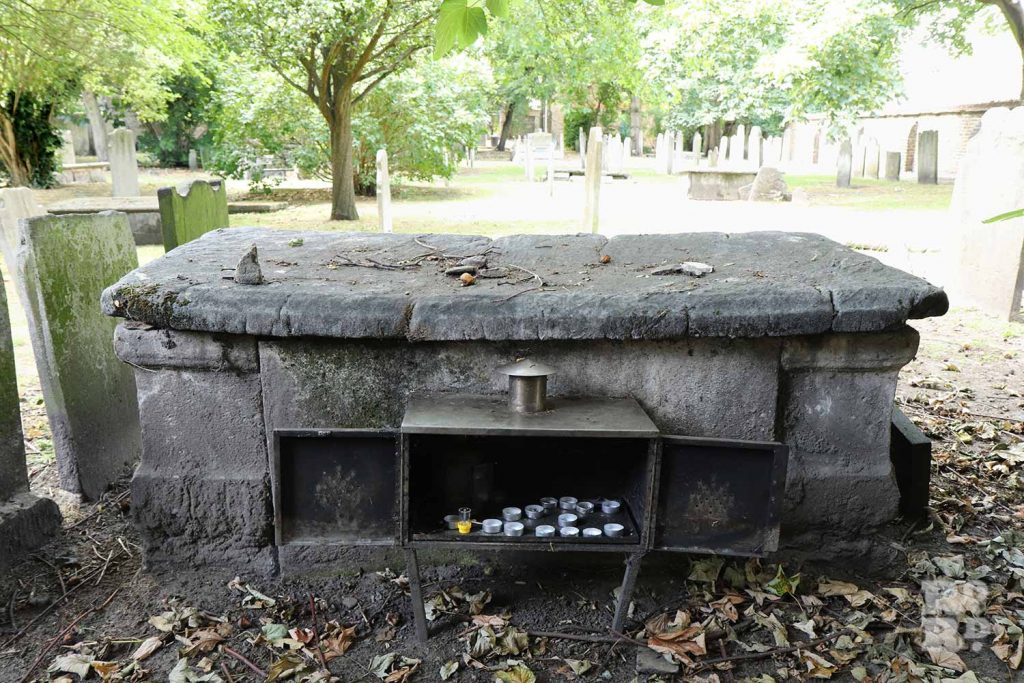

Ba’al Shem of London’s grave in Mile End’s Alderney Road Cemetery

As part of our series about our Jewish heritage, citizen journalist Siri Christiansen revives the memory of the Ba’al Shem of London (c. 1708–1782), the East End kabbalist, alchemist and folk healer, laid to rest in Mile End.

Behind an anonymous brick wall in Alderney Road off Mile End Road lies the oldest Ashkenazi cemetery in the U.K. Founded in 1696 by a Jewish community leader, Benjamin Levy, the cemetery marks the establishment of the Ashkenazi community, now the largest Jewish ethnic group in the U.K.

It also houses many other famous figures from the genesis of the Ashkenazi Jewish community in the East End, including the first and second Chief Rabbis of England, Aaron Hart (1709-1756) and David Tevele Schiff (1765 -1791).

Although it is closed to the general public, it is possible to visit with permission. Walking among its raised tombstones (unlike the flat markers of Sephardic cemeteries), one can trace important figures of the Ashkenazi Jewish community until its closure in 1852.

Among the many leaders of the Jewish faith who lay there, there is one particular cracked tombstone belonging to Samuel Jacob Falk that is crowned with pebbles from visitors. It is a humble remembrance of the once-infamous Ba’al Shem of London.

Samuel Falk: the Ba’al Shem of London

As an occult practitioner during an intellectual revolution that sought to eliminate supernatural beliefs, the Ba’al Shem of London was a controversial character who represented everything that the Enlightenment rejected. Therefore, when the history of the Age of Reason was written, he was crossed out.

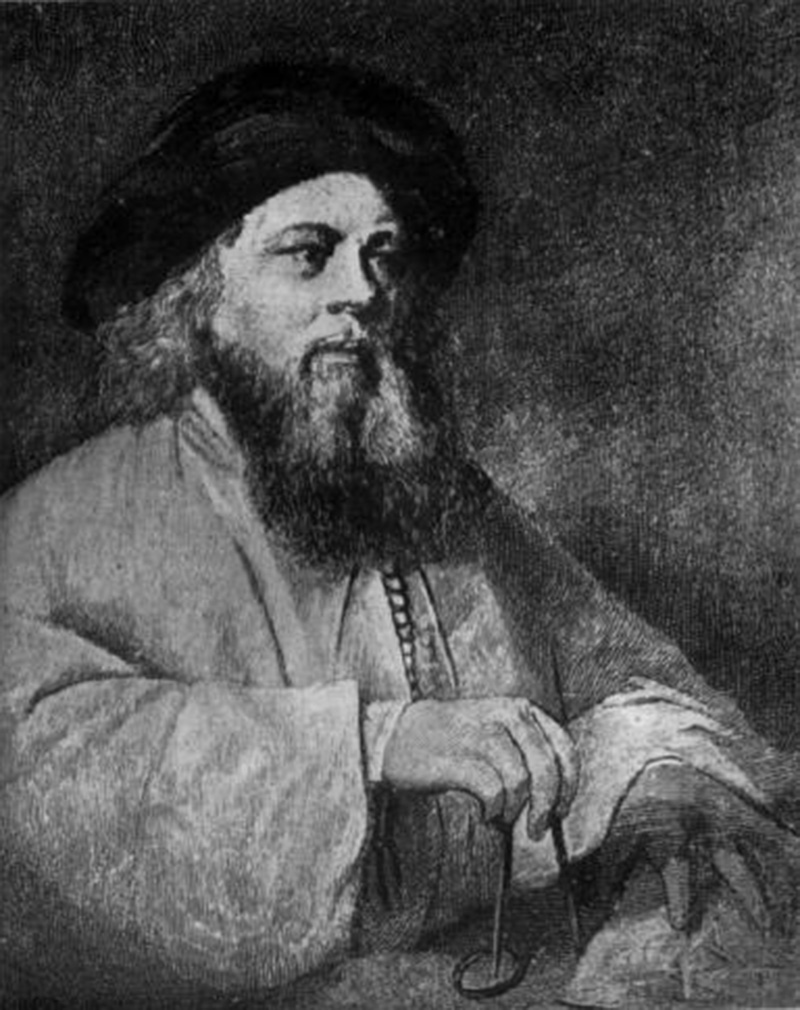

His portrait would later be erroneously identified as the Ba’al Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism, pushing the memory of Samuel Falk further into the abyss.

Nowadays, his tombstone over at Alderney Road Cemetery is one of the few indicators that he ever existed at all. Yet the first line on the plaque affixed to his grave speaks of the high standing he once had: ‘the distinguished elder, the perfect sage, the mystical adept, our teacher…’

Born in Podhajce in modern Ukraine in the early 1700s, Samuel Falk spent the first 40 years of his life travelling through Germany as a Ba’al Shem.

Ba’alei shems, masters of the divine name, were skilled in folk medicine and practical kabbalah (a branch within Jewish mysticism concerning the use of white magic) and offered a wide range of services. By meditating on the holy names and preparing incantations, amulets, or herbal remedies, they could cure illness, reveal lost treasures, conjure angels, predict the future, and offer protection from demons and disasters.

The ba’alei shems operated on a freelance basis and were not tied to the Jewish community. During the early modern period in Central and Eastern Europe, their practice was held in high esteem by both Christians and Jews, who shared the view that misfortune was caused by evil spirits. The natural medicine offered by the ba’alei shems was similar to the standard medical care, but the ba’alei shems possessed a direct contact with the spiritual world that deemed them more effective than physicians.

However, the ba’alai shems were facing increasing scepticism. Enlightenment thinkers and rabbaenites denounced the ba’alei shems as quacks – a direct threat to popular trust in evidence-based medicine. On top of this, Christian fears of occult practices were still lingering after the witch trials.

It wasn’t the easiest time to be a ba’al shem. Sometimes, Falk would be well-received; rumour spread that he cured a Jewish banker’s daughter of epilepsy. Sometimes, not so much – the court of Westphalia in Germany charged him with sorcery and sentenced him to be burned at the stake (before reducing the punishment to lifelong banishment).

It is thought that his network of noblemen eventually led Falk to London in the early 1740s, where he initially took up residence at 35 Prescot Street in Whitechapel before moving to a house in Wellclose Square with his family and assistant. Business soon took off – Falk may have been one of hundreds of ba’alei shems in Eastern and Central Europe, but he was the only wonder-worker in London.

To the Ashkenazi immigrants, the Ba’al Shem didn’t just offer ancient wisdom, but something familiar and trusted. People would often seek Falk’s services for help with epilepsy or mental illness, conditions that science still struggled to explain. Contemporary doctors argued that epilepsy was caused by excessive masturbation, and castrations and clitoridectomies were performed on severe patients until the 1880s. With this in mind, an exorcism might seem like the preferable option.

Many of Falk’s medical wonders have been documented by his assistant. Here’s how he describes one occasion, where Falk is healing the nine-year-old Abraham whose eyes were badly injured from fire:

‘The Sage tied a kerchief over the child’s eyes, placed a pen in the child’s hand, and he wrote a holy name with a mem open on both sides. He ordered the child to throw the holy name into the fire […] and then the child was seized by an epileptic fit. The child lay as dead, and thus he lay for four hours. […] I heard some kind of spell recited by the fire [by Falk], and by night-time the child was as healthy as before.’

These services paid well, but Falk was mainly concerned with his cosmic work. He soon gathered a small group of Jewish students. Together, they engaged in mystical rites in his chamber by London Bridge, in Epping forest or along the shores of the Thames.

The rites would take place at night and last for hours, sometimes until the following morning. The participants would immerse in a ritual bath before gathering at the chosen location, where Falk would prostrate himself and carve out holy names with a knife while his students murmured holy names and prayers.

The occult and ancient sciences enjoyed an unexpected revival as the latest exotic trend amongst the Christian aristocracy, and Falk was quick to seize the opportunity of noble patronage. Reports of Falk’s powers soon reached mainland Europe and attracted the curiosity of prominent Freemasons, aristocrats and adventurers, who pilgrimmed to London to witness his wonders.

The admiration and monetary support by prominent Masonic leaders stirred the antisemitic conspiracy that Falk was the ‘Unknown Superior’ of the Freemasons, and a growing number of rabbis began to criticise Falk for abusing kabbalah for profit and fame.

His clients included Theodore Stephen Freiherr von Neuhoff, a German adventurer who temporarily became the king of Genoa after encouraging a coup. Falk’s association with morally dubious characters like these meant he invited skepticism from within the London Jewish community at the time and led to a surge of conspiracy theories about his activities.

But despite the controversies surrounding him, Falk had a highly successful career. Ba’alei shems were dependent on a good reputation, and the fact that Christians and Jews from all social classes continuously sought Falk’s services over four decades suggests that a lot of people deemed him legitimate.

His respected standing in the community eventually led to the request to appoint Falk as the ba’al bayit (a communal leader) for the London Jewish community in the 1760s. Falk replied “I am ba’al bayit for all of the world” and declined out of principle, but expressed his care for the local community through contributions to Jewish philanthropy.

A few days after drafting up his will, which left most of his wealth to Jewish charities and synagogues, Hayyim Samuel Jacob Falk died unexpectedly on April 12, 1782, and he was laid to rest in the Alderney Cemetery in Mile End.

The Ba’al Shem of London isn’t representative of the intellectual revolution in which he lived in, but his example provides a glimpse of the unrecorded beliefs of ordinary men and women. Falk’s popularity tells us that no matter the scientific advances, there was still a high demand for ancient wisdom rather than modern medicine.

To this day, devoted followers visit his grave, to show their respect and devotion by placing pebbles on his gravestone.

The Alderney Cemetery officially closed in 1852, but it can be visited by making an appointment.

Quotes and translations of Hebrew have been extracted from Michal Oron’s book ‘Rabbi, Mystic, or Impostor? The Eighteenth-Century Ba’al Shem of London’.

If you liked this article you might also like to read about the oldest Sephardic Jewish cemetery in the UK.

What an interesting article. I live quite close to the cemetary.