‘Raw Materials: Plastics’ exhibition explores the invention of plastic in East London

Not many people know that plastic was invented right here in East London. Well, it was, and Bow Arts has put together an exhibition to prove it. Raw Materials: Plastics is the third iteration of a series about industrial history in and around the River Lea Valley. We spoke with two of the artists involved in bringing it to life – Frances Scott and Peter Marigold.

The exhibition as a whole carries a strong sense of community. The steering group that researched the area’s history was comprised of volunteers mostly based in East London. Many of the items on show have been lent by local collectors, including the Mernick brothers, who run the East London History Society, and Carolyn Clark.

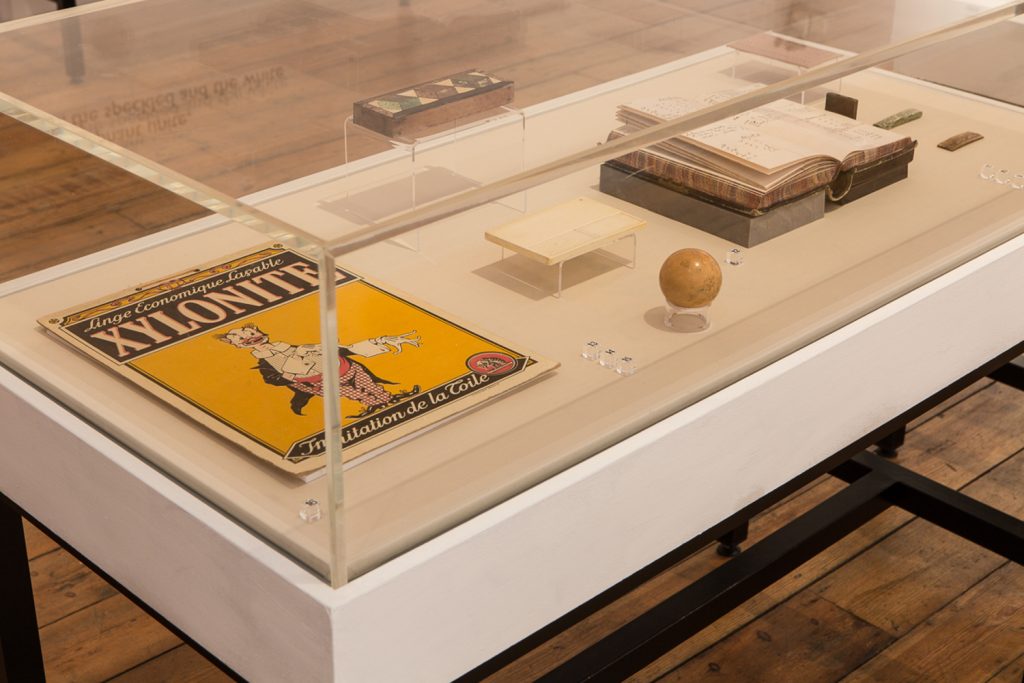

You’d never imagine plastic could be so beautiful. Items on show include shimmering multicolour boxes, hand-carved combs, and billiard balls. (Some of the earliest billiard balls exploded, would you believe, though that never caught on in the pool clubs.) It’s a striking insight into the East End’s mighty industrial past.

Like the two previous iterations of Raw Materials, Plastics is a mix of history and art spanning well over a century. Plastic products hand-carved in the 1860s sit side by side with art installations inspired by the East End’s unlikely invention of plastics. The central figure of the exhibition is the founding father of plastic, Alexander Parkes, who pioneered the material from his Hackney Wick base during the 1860s.

Peter Marigold’s contribution is a series of plastic sheets shaped to a carved wooden mold, harkening back to the early days of plastic when pieces were made individually. Parkes himself carved a number of plastic items during the material’s early days, often behaving more like an artist than to an industrialist.

‘That was probably my favourite part of the story,’ Marigold says. ‘I think inside I am a Victorian. A skilled yet essentially amateur enthusiast, covering a lot of ground, kind of badly but with vigour. My pieces on show focussed very much on the straddling of the worlds of craft and industry that Parkes was positioned between.’

Marigold really is quite a kindred spirit in that sense. He is responsible for FORMcard, a bio-plastic that softens in hot water and can be used to fix things. ‘I think anything that helps people take creative control of the world around them is a massively positive thing.’

It turned out Marigold’s studio was the site of the first fully functioning cellulose nitrate factory, a fact that delights him. Creativity on Hackney Wick took a different form in the 1860s, but it was there. Science went hand in hand with more artisanal sensibilities.

It’s a refreshing balance for Marigold. ‘Industrial designers tend to take themselves way too seriously and I have a fondness of the shoddiness that Parkes excelled at, which sadly led to the demise of the original company also.’

Parkes was adamant that plastic be affordable to regular people. His attempts to make production cheaper did work, but it came at the expense of quality. The Parkesine company folded in 1868 and is often overlooked in the history of plastics.

The exhibition does its best to but that right, and in doing so has unearthed a wealth of industrial history along the Lea Valley, and from the fairly recent past. Victorian times feel so distant in part because they got the ball rolling. ‘It was just a short time ago, and thinking about how fast we’ve developed since then is incredible,’ Marigold says.

Frances Scott contributed a 13-minute film – PHX [X is for Xylonite]. The film shows a series of three-dimensional images of various plastic objects. Appropriately, PHX was itself shot on film, an industry that exists in great part because of plastic.

‘It was important to me that I shot part of PHX on film,’ Scott says. ‘My interest in cellulose nitrate is connected to its relationship to the development of photography and film – Celluloid as it became better known – and how Xylonite was not only used as the base or substrate for film stock, but elsewhere to build props in film production. For example, in the 1956 film adaptation of Herman Melville’s novel ‘Moby Dick’, it was used to construct the prop of the colossal whale, so this production – in the soundtrack – is also embedded in PHX.’

Scott enjoys the analogue process of filmmaking. It pushes for more intense visuals. ‘There is a kind of magic in this, because the end image is always somehow varied to the one you might have imagined.’

The film also has a series of voice overs, with Dr. Miriam Wright narrating extracts from Roland Barthes’ essay ‘Plastics’, colour experiments listed in a British Xylonite Company laboratory formula book, and symptoms of plastics degradation, of ‘crazing’, ‘yellowing’ and ‘bloom’.

‘I wanted to bring together, to synthesise, these elements of my research and it made perfect sense that Miriam, a scientist and lab technician, would read these texts. I wanted the soundtrack to suggest a warped love between the organic and synthetic.’

The Raw Materials project has been a learning experience for Scott as well. Hackney Wick and Fish Island has a long, storied history of innovation. Scott also enjoyed having access to unusual collections and archives, including the private collections of Harold and Phil Mernick, who live in Bromley-by-Bow and run the East London History Society.

Raw Materials: Plastics is an opportunity for locals to learn about yet another way East London shaped the modern world. Plastic is everywhere, so wide reaching that both its positive and negative impact almost beggars belief. And it all started with a tinkerer named Alexander Parkes, whose commitment to his craft seems to have left a mark on practically everyone involved in the project.

‘In the Science Museum stores, they hold Alexander Parkes’ funeral card,’ Scott says. It said “All his labours were to benefit mankind and to do good to all”. This line really stayed with me, and perhaps more than being interested in his role as artist/industrialist, it was his belief in making this material available to everyone, as a Socialist, that resonated. The irony is of course that his invention has had other, much less positive effects, but ultimately his desire was one driven by his progressive politics.

‘It’s really important we can return to these materials in order to make sense of them now, and as artists we are responsible for doing this, for opening up conversations and exchange.’ The Raw Materials: Plastics exhibition gives just that opportunity.

The Raw Materials: Plastics exhibition is running until 25 August. Visit the Bow Arts website for more information

If you enjoyed this piece you may like reading about Kidd & Co, the Fish Island ink works that powered Fleet Street

Petrol was invented in the yard across from the Lord Napier, so it could be said planet wide pollution was also invented in Hackney!