Book review: ‘Canal Tales’ is a rich patchwork of lived histories

Local historian Carolyn’s Clark’s book ‘The East End Canal Tales’, published on the 200th anniversary of the Regent’s Canal’s opening, is a lively patchwork of history and essential reading for every local who considers themselves tied to the canals in some way.

If you live in the East End, you are likely within walking proximity of the Regent’s Canal or the Hertford Union. Many of us enjoy a quiet stroll along the Regent’s Canal to Columbia Road Flower Market or perhaps even follow it down all the way to Limehouse Basin.

However, in its 200 years old lifetime, the Regent’s Canal has been present for many key developments in British history. Carolyn Clark’s book, The East End Canal Tales tells the rich history of the industries, lives and livelihoods that flourished along the canals.

The strength of The East End Canal Tales, published to mark Regent’s Canal’s 200-year anniversary this year, is that it is not just for history nerds. Instead, it is a rich patchwork of lived histories of the everyday people tied to the canals, in their own voices.

There is a short opening chapter where Clark sets out the wider historical context; a quick timeline that, as the title chapter suggests, ‘glides’ through the main points of the canals’ development.

Then the next few chapters, primarily constructed using the voices and memories of those who worked and lived by the canals, are the heart of the book.

This section explores the stories of industry, leisure and general life from the 19th century onward. There is information and quotes gathered from official documents, and written and spoken word testimonies from those who are old enough to remember the canals in the first half of the 20th century, or their surviving family members.

For example, we hear from the lockkeepers. Priscilla Woods once lived in the Acton Lockkeeper’s Cottage further afield in Cambridge Heath and remembers some of the people who lived and worked on the canal.

‘There was a big man called Blossom and a tall thin man who wore a large brim hat called The Pope,’ she says, recalling some of the barge workers. Her quote is accompanied by a black and white photo of Woods.

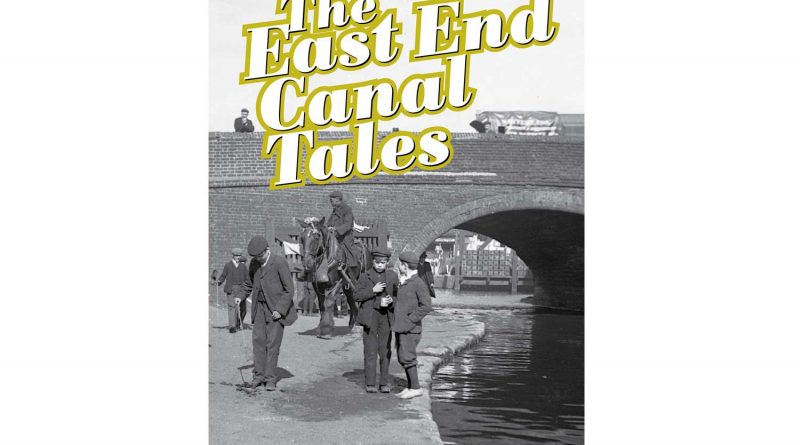

In fact, the use of images is a strong point as Clark generously sprinkles in archive photographs to excellent effect in Canal Tales. She knows just when a visual aid is needed to fully bring to life historical scenes on the canals that will look alien to modern-day readers; there is a particularly striking double page image of a floating barge piled high with coal.

In fact, the book would have benefitted from being published as a larger, hardcover coffee-table publication so that the images could be fully absorbed in a casual flipping of pages. Nevertheless, the small, paperback copy is the right size to tuck into a back pocket to be taken on your next walk and absorbed on a bench by the canals themselves.

There are memories of the horses that would tow the barges of products to and from factories along the East End waterways (there was a horse called Johnny who was fond of apples, another lock keeper recalls), and there are also plenty of accounts of those who worked in the factories during the industrial boom.

It is in these stories of workers, mostly found in the chapter entitled Working on the canal, where we gain an insight into the smoky and chaotic working conditions of the timber, coal, gas, and other industries along the canals to an audience who largely know these waterways as places of greenery and leisure.

Wally Berwick remembers, ‘When I moved to Carr Street in 1962, I’ll never forget the nasty, gassy stinky smell of the gasworks.’ Nowadays, the remnants of these very same gasworks along Bow Common and Bethnal Green are picturesque relics of a bygone age. Similarly, there are testimonials of the dusty atmosphere of the CHS Veneer factory, the very same building that now houses Chisenhale Arts Place.

By knowing when to talk about the wider historical context and when to pull back letting the working people tell their stories instead, Clark resurrects the long gone industrial East End: polluted, poverty-ridden and full of life.

With refreshing honesty, Clark also does not shy away from the harsh socioeconomic conditions of this area in the later chapters. The famous Victorian sociologist Charles Booth describes how the gas workers’ ‘drink like fish’, and there is an entire chapter dedicated to how the East End waterways, with many valuable products moving up and down the water, made them rife for criminal activity.

The final chapters cover how the canals and factories alongside them were mobilised to assist in the world wars even as technological development was already starting to mark the end of the canals’ industrial use.

Clark paints a picture of how these quiet canals were very much part of a key effort in the world wars. There’s a striking description from someone who was school-aged at the time who recalls their teacher telling the class that the boats floating on the canals were on their way to Dunkirk.

Finally, Clark gently arrives at the present day with how the industrial use of canals became redundant, eventually becoming pedestrianised. Yet, she traces the surviving relics so that the reader themselves can appreciate the history surrounding us. These are the gasworks, the still-standing factory chimneys and the waterways themselves.

Overall, Canal Tales are ‘East End Tales’ told by East Enders themselves. It is these stories of the everyday people who lived and worked along the water that brings the 200-year old tale of the canals to life.

This is no textbook that focuses on the big picture, it is a patchwork of social history, portraits of industry, poverty and life arising from the individual voices of the boat drivers, lockkeepers, and local residents. This book is for those who can’t get enough of our local canals, so we can see the water and its many features with the hindsight of history.

A fan of local history? You might also like to read about The Story of the Huguenots.