Along the towpath: 200 years of life on Regent’s Canal

The year 2020 sees the 200th anniversary of the completion of one of our area’s most defining features, the Regent’s Canal.

Cutting across north London from Paddington before heading southward past Bethnal Green and Mile End Park, and finally meeting the Thames at Limehouse Basin, Regent’s Canal today is a place of leisure and play for locals. Joggers exercise along the towpath, families play in nearby parks along its 8.5 mile length, while multi-coloured houseboats lazily float along its sides.

Looking at these scenes of leisure, you would not guess that in a previous life this 200-year old canal played a key role in WWII and before that it helped fuel the Industrial Revolution. Many of the familiar aspects of our East End landscape – the industrial warehouses (now mostly residential flats), the giant gas holders, even the Victoria Park ponds – all exist thanks to this veteran waterway.

1812-1820: The ‘M25 of its day’

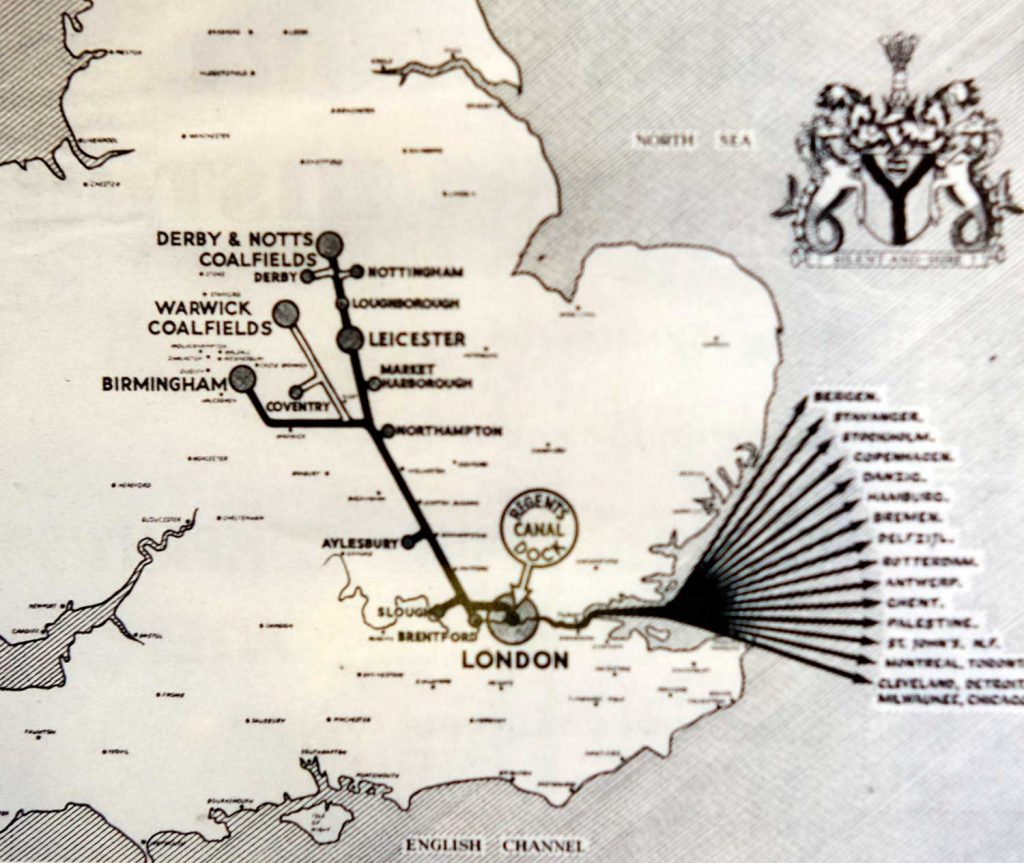

Hard to believe, but when the canal first opened in 1812, the area was largely green and open spaces. Touted as the high speed motorway of its time; historian Carolyn Clark calls it ‘the M25 of its time, Regent’s Canal was purpose-built to move goods from all over the world to England’s industrial heartlands.

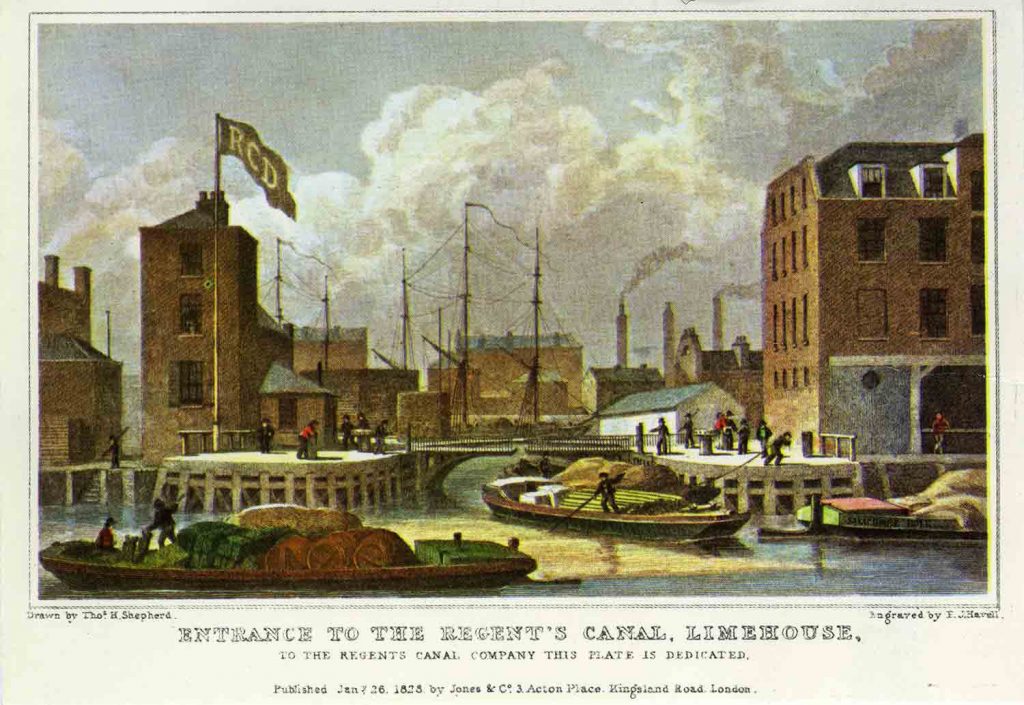

After all, without the A11 and no national railway (yet), a waterway was the most effective way to take products arriving from international waters on the Thames at what is now Limehouse Basin, and transport them to factories elsewhere in England. Regent’s Canal was an especially important access point; it connected the Thames to the network of canals criss-crossing the country.

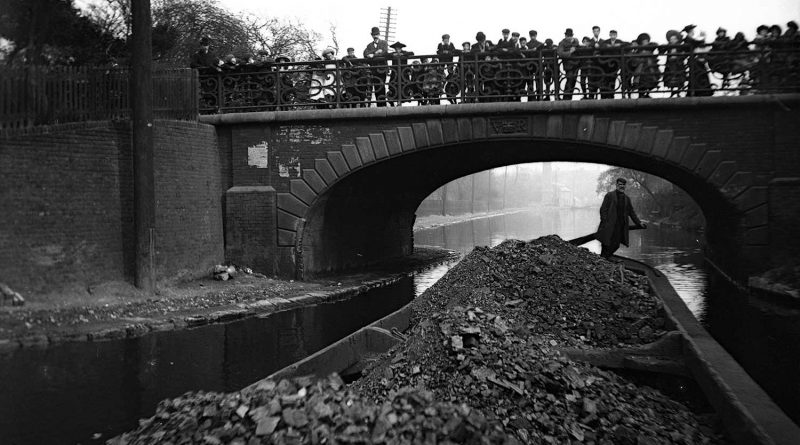

Instead of the multicoloured houseboats of today, the waters would have been full of transport barges and boats, taking all manner of global produce – coal, cattle, corn – to the industrial heartlands of England.

And instead of towpaths full of joggers and cyclists whizzing past you on their way down to Canary Wharf, there were horses pulling barges of products at a more sedate speed of about four miles an hour. Still, in the absence of engine-driven mass transport vehicles, horse-driven barges were still the most effective form of transport at the time.

1850-1900: The industrial development of the East End

Next time you walk along the peaceful greenery of Victoria Park or Mile End Park by Regent’s Canal today, imagine how busy and polluted the canals would have been 150 years ago at the peak of the industrial revolution.

By this point, the East End was well and truly industrialised. Hertford Union Canal joined the existing canals in 1830, connecting the Regent’s Canal to the River Lea. Factories, houses and businesses sprung up along the canal banks and even further inland.

It was around this period that many of the buildings we associate with East End today were built. The characteristic warehouse-style buildings we see lining the canals on our walks were built during this industrial boom – including a wooden veneer factory on Hertford Union Canal, which is now Chisenhale Arts Place, the Bryant and May Match Factory (which still stands as Bow Quarter) and the glue factory that is now East London Liquor Company.

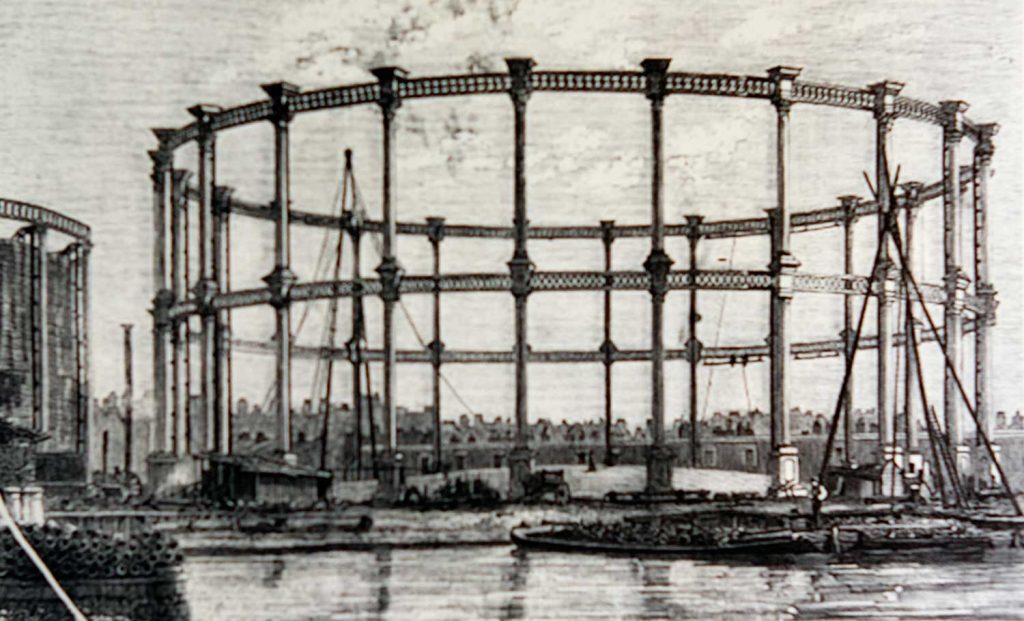

Gas holders and nude bathers

Regent’s Canal was also responsible for the impressive gas holders that we walk past on a Saturday on our way to Broadway Market. Gas power obtained by burning coal was responsible for lighting up much of Victorian England, so these structures were built alongside Regent’s Canal to easily access the coal shipped down from mines in northern England.

One of Regent’s Canal’s unintended uses is that it helped the poverty-stricken and crowded people of East London maintain their hygiene. For many men, illegally bathing in Regent’s Canal could very well be their only option to clean. It is thought that this epidemic of bathing naked men (much to the horror of the police) led to the development of the public bathing lakes in Victoria Park.

Then, as the Industrial Revolution headed towards the 20th century, coal would be shipped in on newly built railway tracks, but Regent’s Canal and the other waterways were still in use on a more local level, delivering products and materials across London.

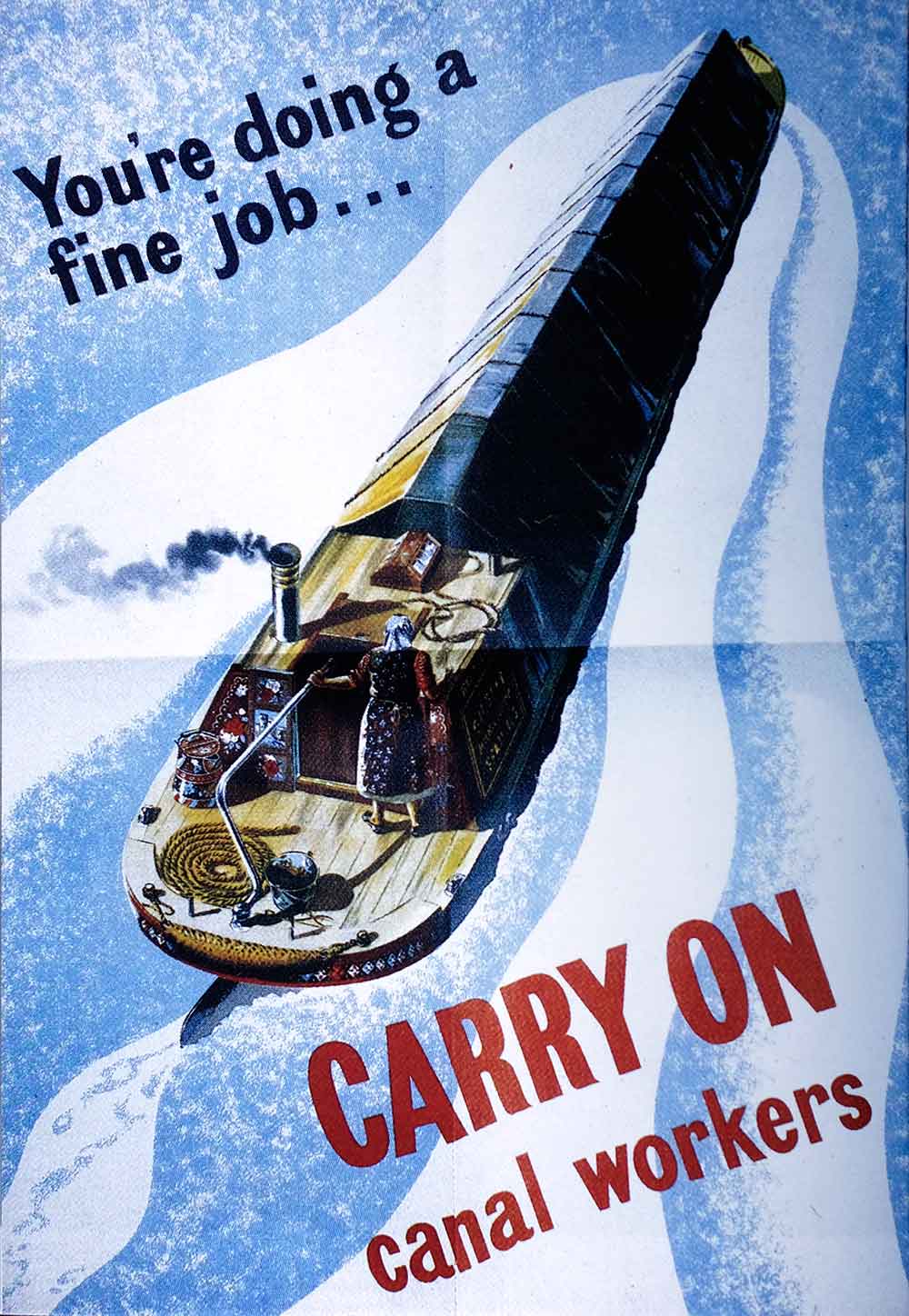

WWII: ‘Target A’ in the Blitz

Regent’s Canal was a key route transporting weaponry and ammunition, many of which were made in the factories here. Unfortunately, this meant the East End, especially the canals, became the German Airforce’s ‘Target A’. The banks of Regent’s Canal were devastated, and the area that is now Mile End Park was especially hard hit, with an estimated 54 bombs dropped in Mile End alone. Prior to the opening of the park in 1999, the land remained abandoned.

During WWII there are reports of locals getting shocked at the sight of a tank floating down Regent’s Canal on a flat decked barge. And many existing factories adapted their business to help out; for instance, chemical plants would manufacture medicine and even timber factories like Cohen’s Veneers – now Chisenhale Arts Place – started making Spitfire cockpits and propellers.

Such was the extent of damage to Regent’s Canal, we are still unearthing artefacts from this era; two volunteers discovered a live WWII grenade in 2014 while clearing up parts of the canal by Salmon Lane Lock.

Houseboats, joggers and canal walks

After the wars, modernity meant the canals’ industrial use was all but redundant. The winter of 1962-63 saw one of the coldest winters on record (known as the Big Freeze), stopping all industrial passage along the canal for three months. It was the final blow for canals-as-industry.

The canals and towpaths, once reserved for workers and horses pulling industry materials, became open for general public use in 1968, marking the beginnings of the Regent’s Canal we know today.

And finally, the following year Regent’s Canal Dock – where Regent’s Canal once met boats from international waters along the Thames – was closed for commercial use and renamed Limehouse Basin, now lined with luxury flats and houseboats for wealthy bankers working at nearby Canary Wharf.

The chapter of industry had now closed for our waterways, making way for the Regent’s Canal we enjoy today.

Regent’s Canal is an ever-present part of our lives. We jog beside it, we walk over it to get to Bethnal Green. We live in flats overlooking it and perhaps even live on it. But over its 200-year existence, the canal has also quietly helped shape the very area we live in, from its past lives first as the ‘M25’ of in the Industrial Revolution, to its last hurrah in the war efforts.

The factories pumping coal-fuelled smoke may no longer be there, but we are reminded of this area’s history in the shells of industrial buildings that have taken on new lives as residential flats, or as bars and breweries. Regent’s Canal is a testament to the continued, yet constantly shifting history of the East End.

With special thanks to Carolyn Clark for providing photos and information from her book, East End Canal Tales, which can be bought from the Canal Museum’s online bookshop.

The East End Canal Festival, originally planned this summer to mark the 200th anniversary of Regent’s Canal, has been delayed until next year due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

If you like this, you might like to look at Victorian poverty maps of London or read about how canal life can provide a respite from London living.