Hooked on urban fishing: ‘It’s about being out there, connecting with nature and appreciating life.’

London has long been home to a fishing tradition of its own. Here, local photographers Tom Hains and Ash Gardner capture the essence of what it means to fish in the East End. Words by Anna Lamche.

The sport, known today as ‘urban fishing’, is really as old as the River Thames itself. For millennia, people have caught fish in London’s waters, first seeking sustenance, and, later, sport. ‘People used to fish for eels out the Thames and take them home for cooking,’ says Chris Kimberley, one of Bow’s many dedicated fishermen.

These days the sport is closely regulated by the Canal and River Trust, which hands out rod licenses and fishing permits. Anyone over the age of twelve must carry a rod license, and if they want to use the canals they need a wanderer’s license too, the former costing £30, the latter £22.

On top of this, all inland fishermen must respect a “catch and release” policy. ‘There is a clear code,’ says Kimberley simply. ‘You do not take the fish out of the water.’

For East End fishermen, there is a wide variety of places to fish, from the small lake in Victoria Park to the canal network and the River Lea.

Leafy Victoria Park is busy with joggers and dog walkers, while crowds often throng the narrow towpaths. Those seeking quieter environments head north up the River Lea, or else take a trip to the fisheries out in Essex.

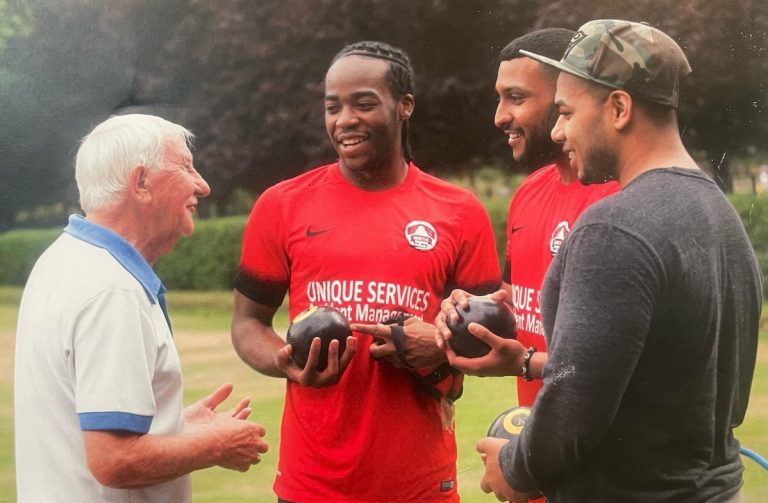

East London in particular is home to a vibrant fishing community, largely thanks to the area’s extensive canal network. Specialist angling store Roman Tackle has served as a hub for this community for 21 years.

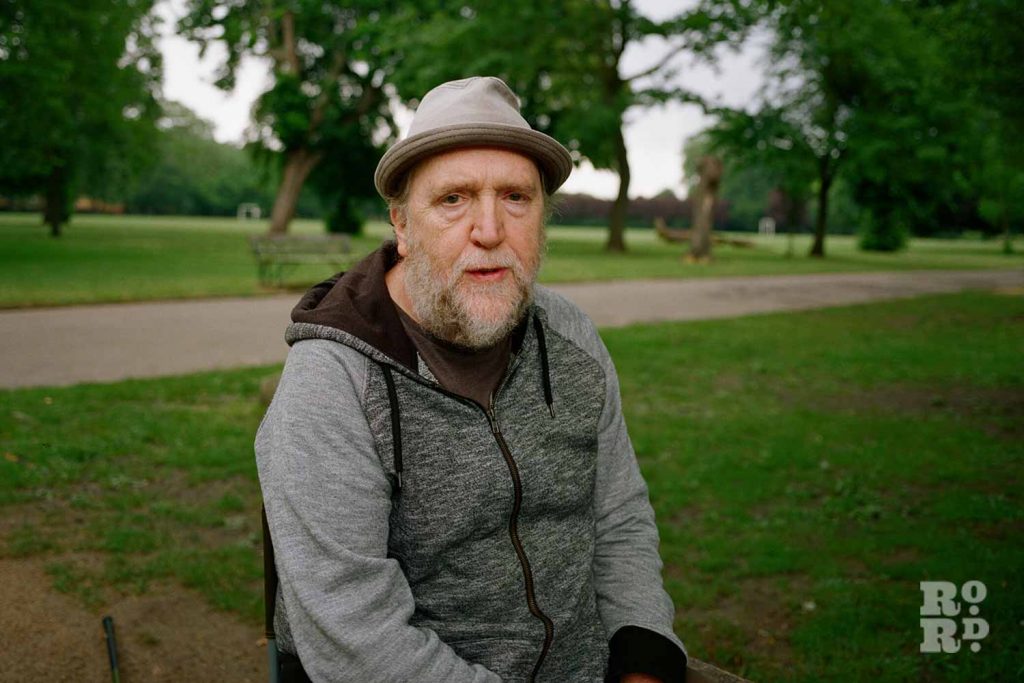

In the past, the city’s waterways were a vital resource, offering reliable and nutritious food for London’s poor. ‘There is a certain tradition,’ says artist and urban fishing enthusiast Bernie Wighton.

‘The East End being where it is, there’s always been a lot of movement of people. That partly goes back to the days of the docks.’ People from all over the world landed in the docklands, once the logistical hub of the British Empire. In this cultural and linguistic melting pot, fishing was a practice that all people, no matter where they were from, could understand and share.

Much has changed since then, including the size of the fish. In Victoria Park and along the canals, you’re more likely to catch what Kimberley calls ‘baby fish’ today. This is partly due to pollution.

‘The quality of fish in the canal around the East End has deteriorated somewhat over the years, mainly because of pollution, the number of boat users,’ Wighton says.

Over the last few years, there has certainly been an explosion in the popularity of houseboats: according to the Canal and River Trust the number of houseboats in the capital increased by 84 per cent to 4,274 between the years 2012 and 2019.

While the energy consumption of a houseboat is much lower than a typical two-bedroom house, large numbers of houseboats are capable of upsetting the delicate ecosystem in which fish thrive.

Legally, houseboats can dispose of ‘grey water’ – wastewater from onboard sinks, showers, air conditioners and washing machines – directly into the waterways. While many boaters use eco-friendly cleaning products, this isn’t always possible.

That being said, fish do still swim through the canals. Recently, Wighton’s angling friends have seen bream swimming in the waters around Stratford. ‘There are fish in the canals but it’s quite hard fishing,’ Wighton says.

In the East End, urban fishing still serves an important social purpose, creating common ground and forging connections between men. And it is generally men – ‘there’s definitely a lot more women in fishing which is brilliant,’ says Wighton, ‘but there’s probably still more men.’

Kimberley, who uses a mobility scooter to get around, says fishing ‘gets me out the house, and I socialise when I get out.’ He lives alone, so fishing in Victoria Park is a great excuse to meet up with friends and other fishermen.

In Wighton’s experience, fishing allows men to open up to each other and discuss their problems. ‘What I find is that men will often share things when they’re doing stuff with somebody else,’ he says.

Passersby tend to open up to Wighton too. ‘It’s surprising the number of people who stop and talk about their problems,’ Wighton says. ‘I’m obviously somebody to be trusted, an old fella’ fishing by the water’s edge, so I’ve had some very interesting conversations.’

He’s offered advice and support to all kinds of people passing by, whether it’s ‘a broken marriage or health problems.’

For Richard Parker, 38, and his ten-year-old son Reggie, fishing is a great father-son activity. ‘We like bonding, getting out, having a good laugh and trying to beat our personal bests,’ says Parker.

Based in Bow, they’ll travel out to fisheries in Essex, where they’ll plot up in a bivvy and fish for carp. ‘I like the camping side of it, staying out in the bivvy, making breakfast, making cups of tea,’ says Reggie.

Fishing is an activity passed from father to son; Richard’s father taught him to fish, and he in turn taught his own son, Reggie. ‘I always went with my Dad,’ Richard says. ‘But we used to go as a big group, a few of my cousins, my dad and my uncles.’

Parker grew up in the area and remembers being Reggie’s age. ‘Up and down the canal, whatever way you went, there was always fishermen,’ he says.

Like Reggie and Richard, Wighton was also taught to fish by his father. ‘We used to go fishing with my dad,’ he says. ‘What I liked was lying in bed and then my dad quietly waking me up about five o’clock in the morning,’ he says.

Wighton used to fish with his family in Battersea Park. ‘My older brother couldn’t sit still,’ Wighton remembers. ‘He was always kind of fidgeting about, messing about, whereas me, I’d just sit there. My dad always used to say he liked taking me because I was patient,’ he says.

These memories mean a lot to Wighton, whose father passed away when he was eleven. ‘Those were exciting days, doing something special with my dad,’ he says.

For Kimberley, urban fishing is the best way to relax. ‘If you’ve been working, you go out for a couple of hours and your stress just drifts off. Plus you’re in a nice environment,’ he says.

Fishing certainly makes you more attuned to the natural world. As Wighton says, ‘you can be sitting there and one minute you’ve got a rat running past you, next minute you’ve got butterflies or a robin sitting on the end of your fishing rod.’

Ultimately, fishing is about more than catching fish. ‘It’s like life, isn’t it?’ says Wighton. ‘Full of joys and sorrows and disappointments but fundamentally it’s about being out there, connecting with nature and appreciating life.’

Photography by Tom Hains and Ash Gardner.

If you liked this, take a look at our photo essay of Victoria Park’s roller-skating revival.